Chapter 2: Social Justice in Settlement Work

Multiculturalism and Myth-Making in Canada

I. The Great American (Meritocratic) Myth

Many people born and raised in Canada are familiar with the concept of the “American dream” and its twin concept, meritocracy. Alvarado (2010) contends that central to the American dream is the idea that the United States is a meritocracy (or country of boundless opportunity), and that people have the opportunity to succeed based on their own merit, which is loosely defined to include a person’s abilities, work ethic, attitude, and integrity (p. 12).

Although the concept of meritocracy can appeal to a person’s sense of responsibility for their own success, the opposite is also true. If one were to consider that they have equal opportunities for success in life, then they would recognize that they are chiefly responsible for their failures as well. The danger embedded within the idea of meritocracy lies in the obscuring of structural barriers that can prevent people from reaching their full potential and lead them to develop an internalized negative self-worth, one where they feel they “deserve” to fail (Collier, 2018, p. 5).

This danger becomes more apparent when one considers the following statistics on race and poverty in the United States. In the United States, Indigenous peoples have a poverty rate that is roughly two and a half times higher than it is for white people, followed closely by Black individuals and people who are Latin American (or Latinx) (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2021). Almost three-quarters of white people own their own homes, but less than half of Latinx and Black Americans do (Statistia, 2020), and Black Americans are approximately five times as likely to be incarcerated as white Americans are (Nellis, 2016). Finally, Black Americans on average have a life expectancy that is four years shorter than it is for white Americans (Arias & Xu, 2020).

Although it would be unreasonable to argue that such statistical disparities could be the result of personal choices that lead to failures alone, meritocratic narratives assume equal opportunity for all, and therefore do not leave room for discussion on how factors such as a person’s race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or class can limit an individual’s opportunities for success. This has the effect of ensuring that the American dream remains a myth (although a powerful one) in discussions regarding social justice in the United States.

II. The Great Canadian (Multicultural) Myth

Although it may seem strange to devote an appreciable amount of time towards a discussion of myth-making in American society, such conversations are vital for settlement workers in Canada to be cognizant of. Such myths offer important insights into the powerful assumptions that lie at the heart of Canadian society—assumptions that are instrumental in the construction of what people think it means to be Canadian.

For example, Millar (2017) contends that we have our own Great Canadian Myth, that multiculturalism in Canada denotes an absence of systemic racism. Given that Canada has been built and sustained by immigrants since its inception, and given that state multiculturalism has been official government policy in Canada since 1971 (McCreary, 2009), Canadian society cannot therefore be racist.

Thobani (2007) offers several important insights into the origin of this narrative and how it came to be so prevalent in mainstream cultural narratives in Canada. To begin, she argues that in the dominant narrative of Canadian society, to be “Canadian,” one must be a law-abiding, enterprising, caring, and compassionate individual who is committed to the values of diversity and multiculturalism. This narrative further suggests that contemporary Canadian identity was forged by the nation’s original settlers who overcame great adversity in founding the nation and did so in the face of serious challenges from “outsiders” who threatened to destabilize or undo the creation of Canadian society as “we” know it. These outsiders were of a different “stock” from the original settlers, who were of Western European origin, and continue to be overrepresented on the margins of Canadian society today (Thobani, 2007, p. 4).

European systems of governance were brought over with the original settlers, and great importance was placed on “rational” thought in the development of the national subject, or “citizen.” Other ways of thinking and being, particularly those of non-Western immigrants and Indigenous peoples, were seen as either “foreign” or “threatening.” These lawful, industrious, and God-fearing individuals laid the foundations for what would later become the Canadian state, and they did so in a manner that was supposedly less violent than in the United States (Thobani, 2007, p. 35).

But missing in this narrative is the construction of “which” laws were created by “whom” and for “what” purposes. The Doctrine of Discovery lies at the heart of many colonial narratives in Canada and portrays North America as a vast wilderness “tamed” by hardy Europeans. This narrative completely erases Indigenous nations from Canadian history—history that is then taught to future generations as “fact” in state-sanctioned public education (Shanahan, 2019).

III. Historical Anti-Immigrant Sentiment

As a result, in their quest to become “more Canadian,” immigrants and refugees have often aligned with colonial narratives for the chance to attain some benefit associated with assimilation. However, migrants who become citizens and successfully integrate into Canadian society are never able to fully shed their labels as immigrants or refugees. Regardless of how long they may have lived in Canada, a non-white person is far more likely to be asked where they are from than a white person is (Thobani, 2007, p. 155). The following examples provide a vivid illustration of the historical (and institutional) racism encountered by people of colour upon arrival in Canada.

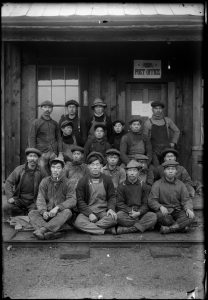

A. Anti-Chinese Sentiment in Canada

Unfortunately, although immigrants from China have long maintained a presence in Canadian society, Chinese immigrants have endured much discrimination in Canada. Immigrants from China played a key role in the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1870s—a key railway that connected British Columbia with the rest of Canada. Despite only earning roughly half the wages paid to white Canadian workers—and having money deducted for food—as well as dying at a much greater rate than their non-Chinese counterparts, Chinese workers were not recognized for their efforts when the railway was completed (Government of British Columbia, n.d.).

To make matters worse, in 1885, the Canadian government passed the Chinese Immigration Act, which instituted a mandatory entry fee, or “head tax,” of $50 for every Chinese immigrant in Canada (Library and Archives Canada, 2021a). When this was not successful in stopping the flow of immigrants arriving from China, the head tax was raised to $100 in 1900 and to $500 (equivalent to two full years’ wages) in 1903 (Chan, 2016). In 1923, restrictions on Chinese immigrants were tightened further, and immigration from China was effectively banned, though exceptions were made for small numbers of merchants, diplomats, and foreign students. This piece of legislation was not repealed until 1947 (Canada Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, 2021a).

It is important to recognize that antipathy towards Chinese immigrants in Canada did not stop with the head tax. In 1907, thousands of Canadians rallied in downtown Vancouver to protest increasing immigration from China, Japan, and other Asian countries. The rally was organized by a group calling themselves the Asiatic Exclusion League and was aimed at pressuring the government to enact policies to “keep Canada white” (Mackie, 2017). The rally quickly turned violent as participants attacked Chinese-owned businesses and homes in areas that had higher numbers of Chinese and Japanese immigrants (Laurier University, 2020).

Finally, in 1908, the Canadian government passed the Opium Act, the first anti-drug law in the country. The Act criminalized the production, distribution, possession, and consumption of opium, and was passed in response to the federal government’s perceived concerns about the negative influence of Chinese opium on young, white Canadian girls (Carstairs, 1999, p. 69).

In 2006, former prime minister Stephen Harper offered an official apology and symbolic reparations to Chinese Canadian families harmed by the head tax (Clark, 2006).

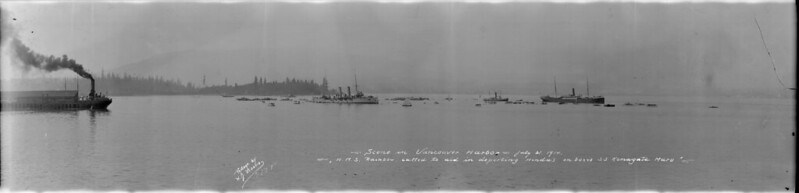

B. The Komagata Maru Incident and Anti-Indian Sentiment in Canada

In 1908, the federal government passed the Continuous Journey Regulation. An amendment to the Immigration Act of 1906, this new regulation stated that a person would not be permitted to immigrate to Canada if they did not travel to Canada directly from the country of their birth or citizenship. It was largely targeted towards people from India (and to a lesser extent, Japan) who could not physically make a journey directly to Canada by ship and were deemed to be “incompatible” with the climate and way of life in Canada (Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, 2021b).

In response to terrible economic conditions in their home communities, 376 passengers boarded the Komagata Maru in India and set sail for Canada. The ship’s long voyage had them travelling from Calcutta to Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Yokohama before arriving in Vancouver (McRae, 2021c).

Unfortunately, upon arrival in Canada, the Komagata Maru was not allowed to dock, and the passengers were prohibited from leaving the ship. In essence, the ship remained a floating prison for approximately two months; no one was allowed on or off, and the people on board had restricted access to food and water (McRae, 2021c).

However, established Indo-Canadian communities organized support for the passengers, to which the federal government responded by sending in the army and police to force the ship to turn around (University of the Fraser Valley, 2021). In the end, out of the 376 passengers aboard, only 24 merchants were allowed to stay, and four months after the ship set sail, it arrived back in Calcutta. In the ensuing riot that took place in India, 16 people were shot and killed by police, and more than 200 others were arrested on suspicions of being political revolutionaries (McRae, 2021c).

Former prime minister Stephen Harper informally apologized for this incident in 2008, and a formal apology on behalf of the federal government was issued by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in 2016 (CBC News, 2016).

C. The War Measures Act and Ukrainian Internment Camps

In 1914, the federal government passed the War Measures Act in response to Canada’s entry into World War I (Smith, 2013). The Act allowed the government to suspend civil liberties in times of war or national crisis and was in effect from 1914 to 1920. Approximately 80,000 people who immigrated from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, most of whom were Ukrainian, had to register as “enemy aliens” with the federal government and were subsequently subject to routine policing, monitoring, and harassment. The government also confiscated their money and property (McIntosh, 2018).

Between 5,000 and 10,000 Ukrainians were interned in 24 work camps scattered across Canada and were used as forced labour to create the basic infrastructure for national parks in the Canadian West. They were paid low wages, had money deducted for their lodging accommodations, and were subjected to harsh treatment from guards. One hundred and seven people died in the camps—six were shot trying to escape, and the others died from disease, injury, or by suicide (McIntosh, 2018).

In 2008, the Canadian government created a trust fund for the Ukrainians and other diaspora communities impacted by the internments to commemorate this sad chapter of Canadian history (The Canadian Press, 2008).

D. The War Measures Act and Japanese Internment Camps

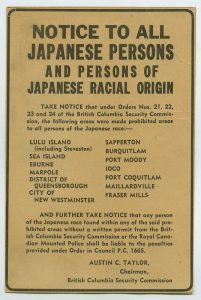

The federal government re-enacted the War Measures Act in 1939 following Canada’s entry into World War II, which remained in effect until 1949. After the bombing of Pearl Harbour in the United States by the Japanese military, Canada subsequently declared war on Japan, and Canadian society saw a dramatic increase in anti-Japanese hysteria, which was inflamed by the media (Marsh, 2012).

All men of Japanese origin aged 18 to 45 were arrested and dispersed to one of 10 internment camps across Canada (McRae, 2021a). All property and money they owned was confiscated and sold by the federal government to non-Japanese Canadians, 4,000 people were stripped of their Canadian citizenship and deported to Japan (Library and Archives Canada, 2021b), and 23,000 people were displaced and/or interned by the Canadian government in forced labour camps, despite the fact that 75% of these people were either Canadian-born or naturalized residents in Canada (McRae, 2021a).

In 1988, then–prime minister Brian Mulroney publicly apologized for what happened to Japanese Canadians during World War II and announced compensation of $21,000 for every Japanese person impacted by their forced displacement (CBC, 1988).

E. Antisemitism, Jewish Refugees, and the MS St. Louis

In 1933, the National Socialist (Nazi) Party, led by Adolf Hitler, consolidated its power and control in Germany. More than 800,000 Jews fled Nazi Germany after being stripped of all their property and threatened with violence by the paramilitary wings of the government. Canada accepted only 4,000 Jews in total between 1933 and 1939 (Kleinmann Family Foundation, n.d.), with a senior government official reportedly stating that “none is too many” when discussions of admitting Jewish refugees arose within government circles (CBC, 1982).

In addition, on May 13, 1939, 937 Jewish refugees boarded the MS St. Louis after losing their businesses and homes, hoping to settle in the Americas (Yarhi, 2015). Upon arrival in Havana, Cuba, only 29 passengers were able to leave the ship, and after two weeks, the MS St. Louis was ordered to leave. Subsequent calls for asylum to the governments of Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Panama were rebuffed, and pleas to the Government of the United States were not only refused, but the American government sent a warship to accompany the MS St. Louis as it sailed north (Kleinmann Family Foundation, n.d.).

Canada’s response was similarly shameful. The federal government stated that this was “not a Canadian problem,” with Director of Immigration Frederick Blair going so far so as to officially state that “No country, could open its doors wide enough to take in the hundreds of thousands of Jewish people who want to leave Europe: the line must be drawn somewhere” (Yarhi, 2015). Faced with no other alternative, the ship returned to Europe, and 254 of its passengers died in the Shoah (Holocaust).

In 2018, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau officially apologized for the Canadian government’s decision to formally turn away Jewish refugees aboard the MS St. Louis (Abedi, 2018).

F. Slavery and Anti-Black Racism

Many people born and raised in Canada are at least somewhat familiar with the problematic history and legacy of slavery and systemic anti-Black racism in the United States, but Canada’s treatment of Black Canadians is far less well known, and even less discussed.

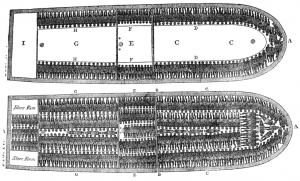

Lands that are now part of what we call Canada participated in the transatlantic slave trade for over two centuries (McRae, 2021d). Although not as widespread as it was in the United States, slavery in the territories of British North America still referred to people as being the property of slaveowners, and it was not uncommon for enslaved people to be horribly punished for whatever the “slaveowners” felt was an infraction. This was illustrated by the flight of enslaved individuals from Canada to the State of Vermont in 1777 because Vermont had abolished slavery at a time when it was still legal in Canada (Ostroff, 2019).

However, it is important to recognize that attitudes towards slavery began to change in the Canadian territories much more quickly than in the United States, and by 1834, the institution of slavery had been outlawed throughout all the territories controlled by Great Britain (Henry, 2006). This development allowed for the emergence of the Underground Railroad, which helped enslaved people fleeing captivity to escape to communities that had already abolished slavery. It is estimated that roughly 30,000 people escaped to Canada via the Underground Railroad (Klowak, 2011).

Despite the important though indirect role that Canada played in efforts to abolish slavery, it is important to note that the Government of Canada has not traditionally been receptive to welcoming large numbers of Black immigrants. More than 1,000 formerly enslaved Black people and their families moved from the State of Oklahoma to Western Canada between 1905 and 1912 (Shepard, 1983, p. 2), and their arrival coincided with the federal government passing the Immigration Act of 1910.

The Immigration Act allowed the Canadian government to deny immigration status to any individuals deemed “unsuitable to the climate or other requirements of Canada” (Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, 2021c). It was complemented by the passing of Order-in-Council P.C. 1324, which though never enacted, nevertheless prohibited the immigration of Black individuals, and the passing of a resolution by the Edmonton City Council in 1911 calling on the federal government to prevent mass migration by Black settlers (Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, 2021d). These efforts were bolstered by the sustained political agitation of several groups representing white Canadians hostile to Black newcomers arriving from the U.S. Midwest (Henry, 2019).

These resulting hostilities were reinforced by the federal government, which sent agents to Oklahoma to discourage prospective Black settlers from moving to Canada (Shephard, 1983, p. 8), and ads were published in American newspapers to create the impression that Black immigrants would not be industrious enough to cope with Canada’s difficult soils and cold climate (Mundende, n.d.). Despite establishing a community of approximately 300 people in Amber Valley, Alberta, many Black Oklahoman settlers returned to the United States, whereas many others pursued economic opportunities in cities like Edmonton (Snowdon, 2017).

As a result, it would be fair to suggest that most Black newcomers did not find Canada to be as safe and welcoming as they had hoped. Although slavery had been abolished, Black people in Canada encountered systemic discrimination. Ontario and Nova Scotia passed legislation that created racially segregated schools for white and Black students, while Alberta, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island allowed schools to refuse access to Black children (Henry, 2019).

Segregated schools continued to operate in Ontario and Nova Scotia until 1965 and 1983, respectively, and Blacks encountered refusal of services in restaurants, theatres, and on public transportation for much of the 19th and early 20th centuries (New Youth, 2019). Attitudes towards segregation did not begin to meaningfully change throughout much of Canada until Viola Desmond challenged long-standing policies that reinforced segregation in 1946. Desmond refused to leave the designated “Whites only” section of a local theatre house and was arrested for occupying a seat she did not pay full price for (seats for Black people cost marginally less but did not offer as clear a view of performers) (Bingham, 2013).

Interestingly, Desmond’s courageous activism occurred nine years before far more widely known Rosa Parks helped spark the Civil Rights Movement in the United States (Coletta, 2018). However, it was not until the early 21st century that her enormous contributions towards the fight for social justice were officially recognized. In 2010, the Government of Nova Scotia formally apologized to Viola Desmond’s family (Darrow, 2010), and in 2018, the Bank of Canada featured Desmond on Canada’s new $10 bill (BBC News, 2019).

Unfortunately, though, one might not find a more explicit example of systemic anti-Black racism in Canada than the story of Africville, Nova Scotia. Located on the outskirts of Halifax, Africville was founded in the mid-1800s by the descendants of Black refugees fleeing slavery in the United States shortly after the American War of Independence and existed for almost 150 years. Although many of the Black settlers were enticed to move to Nova Scotia by the promise of land (McRae, 2021b), established white residents were hostile to the mass arrival of the Black emigrés.

As a result, the municipal government in Halifax designated the city’s North End as the most suitable location for these Black families to establish themselves (Khan, 2021). Unfortunately, the land there was the most inhospitable in the area, and to make matters worse, the residents of Africville were denied basic services such as paved roads, running water, electricity, and waste removal, despite the fact that they paid taxes like any other Halifax residents. The community’s pleas for intervention from the provincial government were also ignored (Khan, 2021).

The close to 400 residents who chose to make their lives in Africville faced increasing hostilities from the municipal government; homes were expropriated to construct a railway, and an infectious disease hospital, prison, and garbage dump were placed in close proximity people’s homes (McRae, 2021b). Under the guise of urban renewal and citing public sanitation concerns, the Halifax City Council voted in 1964 to begin a five-year process of forcibly relocating the residents of Africville and bulldozing any homes in the area. Residents were opposed to the idea and saw it as an attempt to destroy their community. The last home in Africville was razed in 1969 (McRae, 2021b).

In 1996, the federal government designated the site of Africville a National Historic Site, and in 2010, then mayor Peter Kelly formally apologized for the eviction of Black Canadian families and the razing of their homes in Africville (Barber, 2010).

G. Colonialism, Genocide, and Anti-Indigenous Racism

Although each of the above examples provides ample evidence to challenge the Great Canadian Myth in its own right, it is the legacy of colonialism and the genocide of Indigenous Peoples in Canada that most explicitly problematizes the denial of systemic racism in this part of the world.

A: Land, Treaties, and Colonialism

When considering the historical relationship between the Canadian government and FNMI (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) groups, it is crucially important to recognize the importance of land to Indigenous Peoples and communities. Although not unique to the Indigenous nations of Turtle Island (the Indigenous name for North America), connections to the land are very closely tied to cultural identity and tradition. Land has historically provided the opportunity to grow food, obtain materials for shelter, and in many cultures, represents a connection to the spiritual world. As a result, knowledge of the land is vital to the survival of many Indigenous cultural practices. The disruption of a people’s connection to their traditional territories has been highly disruptive to their cultural practices and, in turn, to their personal and communal self-identity.

Land is central to colonialism. Stinson (2016) defines colonialism as “a policy or set of policies and practices where a political power from one territory exerts control in a different territory” (p. 1). A key factor in the process of colonization therefore involves sending people from the colonizing country to live on the newly taken-over land; these people are referred to as “settlers” (Osman, 2017). An unfortunate dark side of the history of many countries that have a rich legacy of immigration, such as Canada, Australia, and the United States, is that successive waves of immigration have been used to perpetuate colonial relationships to land, resources, and Indigenous peoples. The Indigenous populations of these territories have subsequently been replaced by waves of migrants, which has ultimately led to the creation of a society that is culturally distinct from the countries of origin of the original settlers. This subset of colonial relations is referred to as settler colonialism (Barker & Battell Lowman, n.d.).

As a settler colonial society, it is important to recognize the importance of land in the development of what has become known as “Canada.” As noted above, the Doctrine of Discovery exemplified colonial logic (Shanahan, 2019), but it is important to recognize that such “discoveries” represented little more than an acknowledgement by European colonists that a given landmass already existed (Belshaw, Nickel, & Horton, 2016). In other words, nothing was actually discovered because people had been living in lands foreign to Europeans for millennia.

Equally important to recognize is the diversity of Indigenous Peoples in Canada and other settler colonial societies. Much like how European countries have their own distinct cultures, languages, and worldviews, so too do the Indigenous nations of Turtle Island. The Assembly of First Nations asserts that there are over 50 distinct nations and language groups across Canada, in 634 First Nation (reserve) communities (Assembly of First Nations, n.d.).

As such, central to the understanding of the legacy of colonialism in Canada is the history of treaties. In short, treaties refer to legal agreements made between governments in Canada and Indigenous Peoples (Government of Canada, 2020). Although these accords define the rights and responsibilities of all signatories, it is important to note that cultural differences in the understanding of what constituted a treaty relationship would lead to tragic consequences for Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

Although the first Europeans arrived in Canada in 1497, the first European settlement in Canada was not established until 1604. Archaeological evidence demonstrates that Indigenous Peoples have been living in Canada for at least 13,500 years, and as such, it became important for European colonists to establish agreements with Indigenous nations upon contact (Canadian Museum of History).

In 1613, Gusweñta, also known as the Two-Row Wampum Treaty, was signed between Haudenosaunee and Dutch leaders and represented an agreement whereby Europeans and Indigenous Peoples would share the land but live separately from one another “for as long as the grass is green, as long as the water flows downhill, and as long as the sun rises in the east and sets in the west” (Powless Jr., 1994, p. 21).

The Gusweñta greatly influenced the Royal Proclamation of 1763, a British government document outlining the guidelines for settlement in what is now known as North America. Significantly, it stated that all land in North America was to be considered Indigenous territory until it was surrendered in a treaty (University of British Columbia, 2009b). The Royal Proclamation was written without input from First Nations representatives and allowed the British “administration” of traditional Indigenous territories and the creation of the first reserves. More importantly, it forbade settlers from claiming land from Indigenous-controlled territories and the granting of land titles by colonial governments unless such land was first bought by the Crown and then sold to settlers. It further set out that only the Crown could buy land from First Nations, and thus inherently recognized Indigenous claims to their traditional territories (Slattery, 2015, p. 14).

These important recognitions led to numerous subsequent treaties (see the Upper Canada Treaties, Robinson Treaties, and Douglas Treaties for more detail) and the eventual signing of the numbered treaties that have come to define Indigenous–Crown relations in Western Canada. Starblanket (2008) asserts that Indigenous perspectives on treaty-making were that treaties were based on peace and friendship and allowed two parallel legal systems to co-exist on the same territory, which was to be shared. In contrast, the Crown felt that it had jurisdiction over Indigenous territories (via the Doctrine of Discovery); the Crown operated as though it had the ultimate authority over the Indigenous territories it claimed and was trying to formalize its control over these lands.

For the Crown, the treaties thus represented a surrender of title to the land and an acceptance of the legal authority of the Canadian government in exchange for certain benefits to be provided. These benefits included the creation of communities on reserve lands, the honouring of hunting and fishing rights, and the setting aside of funds for Indigenous Peoples to adopt more Western ways of living pertaining to agriculture and Eurocentric ways of parenting and educating children (University of British Columbia, 2009a).

The differing interpretations of what the treaties represented, particularly since the treaties were written documents that were signed between Europeans and Indigenous Peoples who had a practice of creating accords and passing on knowledge orally (Canada’s First Peoples, 2007), has resulted in accusations that treaty signings constituted the theft of Indigenous territories by the Canadian government. Unfortunately, the results of treaty-making with the Canadian government have proven disastrous for Indigenous Peoples living in Canada (Facing History and Ourselves Collective, n.d.).

B. Residential Schools and Other Instances of Genocide

Between 1842and 1844, the Bagot Commission (named after Charles Bagot, the then Governor General of North America) conducted a two-year review of conditions on reserves. The Commission concluded that reserves were half-civilized states and made several recommendations for “improving” education on them (Edmond, 2014). Chief among them was the creation of federally-run Indian residential schools for the purposes of separating children from their parents and forcing Indigenous children to abandon their cultures and identities (Rheault, 2011, p. 1).

In 1847, the Assistant Superintendent General of Indian Affairs authored a report indicating that “Indians” needed to be raised to the level of whites. It was decided that the best way to accomplish this was to Christianize them and force them to adopt non-Indigenous values; the first federally-run Indian residential school subsequently opened in Ontario in 1848 (Petit, 1997, p. 15).

In 1876, the Indian Act was passed (Parrott, 2006). The Act criminalized the expression of Indigenous identity through governance or culture, barred Indigenous Peoples from practising their traditional religious ceremonies, determined who was and was not a “Status Indian” based on their paternal lineage, and led to the passage of the pass system, which prohibited travel on and off reserve by any Indigenous person unless they were authorized in advance by a government agent (Indigenous Corporate Training, 2015). The Act also authorized the federal government to take responsibility for the education of Indigenous Peoples and ensured that Indigenous children could be forced to move off the reserve and be assimilated into mainstream Canadian society.

In 1879, the Davin Report, written by journalist, lawyer, and politician Nicholas Flood Davin, called for the aggressive civilization of Indigenous Peoples, referred to “Indian culture” as being a contradiction (Facing History and Ourselves Collective, n.d.), and stated that the aim of education was to “kill the Indian in the child.” The report became the theoretical foundation for Canada’s Indian residential school system (University of British Columbia, 2009d). As a result of Davin’s conclusions, in 1883, the federal government began building residential schools far away from reserve communities (Canadian Geographic, n.d.). In 1892, the government passed operational control of the schools to churches (Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, and Methodist), and in 1894, attendance at the schools was made mandatory for children between the ages of seven and 16; in 1908, this was changed to include children between the ages of six and 15 (Edmond, 2014). Parents who resisted were threatened with large fines, imprisonment, and/or loss of treaty benefits (Fraser, 2020).

In 1907, Dr. Peter Bryce, medical inspector for the Department of Indian Affairs, toured the residential schools of Western Canada and British Columbia and wrote a damning report on the health conditions at the schools. Labelling them “criminal,” Bryce reported that Indigenous children were deliberately infected with diseases like tuberculosis and were left to die untreated as a regular practice (Hay, Blackstock, & Kirlew, 2020).

Bryce cited an average mortality rate of 30% to 60% in the residential schools he surveyed and a practice of poor bookkeeping that made it difficult for outside investigators to accurately determine student causes of death (Annett, n.d.). Bryce was so appalled by what he witnessed that he went so far as to state that in his professional opinion, the state-sanctioned practices in residential schools were acts of genocide (Nandogikendan, n.d.). Bryce’s final report was not published by the federal government (Smith, 2007).

In 1920, the Indian Act was amended to require Indigenous children over seven years of age to attend a residential school for at least 10 months every year (Parrott, 2006). Justifying this amendment, Duncan Campbell Scott, then Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, was quoted as saying:

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone …. Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill” (1920, p. 55, as cited in The Critical Thinking Consortium, n.d.).

In 1928, the Sexual Sterilization Act was passed in Alberta (CBC News, 2010). It allowed any inmate of a residential school to be sterilized upon the approval of the school principal. As a result, 2,834 women and girls were sterilized, with Indigenous women comprising 6% to 8% of this number (Stote, 2019). In 1931, there were 82 active residential schools in Canada (the highest number), and in 1933, residential school principals were made the legal guardians of all Indigenous students (Union of Ontario Indians, 2013, p. 4). Parents were forced to surrender legal custody of their children to the principal or risk imprisonment. Mandatory attendance in residential schools did not end until 1948 (Rheault, 2011, p. 2), and the last residential school closed its doors in Saskatchewan in 1996 (Miller, 2012).

More than 150,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend residential schools, and tens of thousands of survivors reported horrific experiences of physical, psychological, and sexual violence while they attended the schools; at least 3,200 student deaths have been confirmed from official records (Hopper, 2021). However, that number is widely considered to be underreported, and new evidence continues to emerge to substantiate the claim that mortality rates at residential schools were far higher than has been publicly acknowledged (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015).

In response to the horrors encountered by students at residential schools, a group of survivors launched a class-action lawsuit against the Government of Canada. The suit was settled in 2006, which led to a public apology from then prime minister Stephen Harper in 2008 and the creation of the national Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) (Government of Canada, 2021). The Commission operated from 2007 to 2015 and focused on formally documenting the horrors of residential schools.

Members of the Commission spoke to 6,750 survivors, reviewed millions of documents, and ultimately concluded that Canada engaged in a systemic campaign of cultural genocide against Indigenous Peoples (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015, p. 102). In response, the TRC issued 94 Calls to Action to advance the prospect of reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people living in Canada.

Unfortunately, these are not the only acts of genocide and colonial violence that the federal government has been forced to acknowledge and begin to address. In response to growing public pressure, in 2015, the federal government launched a national inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG).

Indigenous women in Canada are three times more likely to be the victim of a violent crime than non-Indigenous women and are seven times more likely to be murdered (Amnesty International, 2014). The persistence of this phenomenon in Canadian society—and the unwillingness of successive federal governments to address it—led the commission to conclude that genocide of Indigenous women has been occurring unabated in Canada (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019, p. 26).

The federal government was also forced to recognize and apologize for the Sixties Scoop. The term “Sixties Scoop” refers to the disproportionate number of Indigenous children who were forcibly removed from their homes and communities, often over the objections of their families, in the second half of the 20th century (University of British Columbia, 2009c). These children were then placed into the homes of predominantly shite, middle-class Canadians, who were responsible for providing them with a “stable” upbringing. Many of the families impacted by the Sixties Scoop consisted of residential school survivors, and apprehended children encountered a loss of their cultural identity as a result of their experiences. Furthermore, the individuals responsible for the “scooping” were often social workers or other social services workers (Alston-O’Connor, 2010, p. 54). The result of this has been a strong and lingering distrust of social workers in many Indigenous communities in Canada (Thibodeau & Peigan, 2007, p. 53).

Watch the following video to review the timeline of these events surrounding the residential school system.

The examples outlined above are not easy to digest or discuss; however, they are very important chapters of Canadian history that problematize the Great Canadian Myth and are thus critical for settlement workers to be aware of as they enter the field. Settlement workers will support many people who are living with the legacy of systemic racism. It is important that any help offered to service users play a role in reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples and not result in the recreation of colonial narratives or practices. The remaining sections of this chapter will provide settlement workers with tools and strategies for adopting an anti-racist and anti-oppressive approach to settlement work.

Learning Activity 2: Knowledge of Canadian “History” Quiz

Although this activity can work well in an in-person think-pair-share format, it could also work well as an online discussion forum topic.

Image Credits (images are listed in order of appearance)

Queen of Liberty by stinne24, Pixabay licence

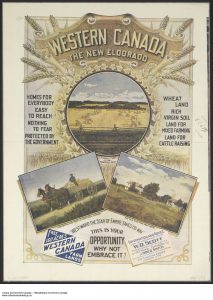

Library and Archives Canada. (c. 1890–1920). Western Canada – The New Eldorado [Poster]. Item ID number: 2945432. https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/collectionsearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2945432

Timms, P. (190–). Chinese men in front of post office [Photograph]. Vancouver Public Library Historical Photograph Collections. VPL Accession Number: 78362. https://www.vpl.ca/historicalphotos

Canadian Photo Company. (1914). Sikhs aboard ship Komagata Maru [Photograph]. Vancouver Public Library Historical Photograph Collections. VPL Accession Number: 136. https://www.vpl.ca/historicalphotos

City of Vancouver Archives. (1914). Scene in Vancouver Harbor – July 21. 1914 “H.M.S. Rainbow, called to aid in deporting Hindus on board S.S. Komagata Maru [Photograph]. Major Matthews Collection. Reference code: AM54-S4-3: PAN N151. https://www.flickr.com/photos/vancouver-archives/5456682537/in/photolist-9jbVBp

Plaque and statue commemorating the Castle Mountain Internment Camp in Banff National Park, Alberta by Radtke67, Public domain.

British Columbia Security Commission Japanese internment notice titled “Notice to all Japanese Persons and Persons of Japanese Racial Origin” by British Columbia Security Commission, Public domain.

Interior layout of a slave ship by House of Commons, Great Britain, CC BY-SA 4.0 International licence

This activity can be facilitated in a face-to-face setting, but would be best suited to an online modality.