Chapter 5: Intercultural Competence and Communication

Improving Intercultural Competence

How We Experience Cultural Difference

Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS)

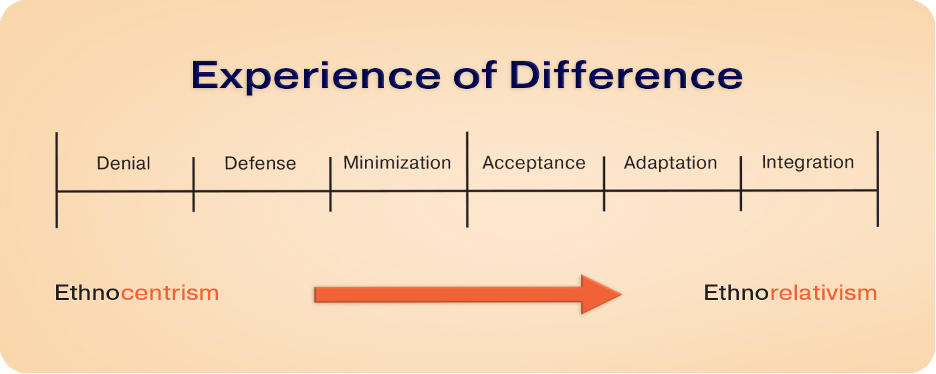

The Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) was created by Milton J. Bennett (1998, 2001, 2004, 2014, 2017) to better understand and support people as they worked towards greater intercultural competency (Bennett, 2004, p. 1). The model and corresponding stages of the continuum were developed based on his observations of people in academic and business settings who were working on becoming more competent intercultural communicators.

Overall, the DMIS describes how we experience cultural differences. On this continuum, Bennett coined the terms “ethnocentric” and “ethnorelative” to describe the two opposing ends. The model describes how a person moves from avoiding difference (ethnocentrism) to seeking differences (ethnorelativism). Those at an ethnocentric stage see their beliefs and values as natural, correct, and unquestioningly the best way to live. They view their cultural experience as the reality. On the other hand, those who have a more ethnorelative view can see the world through a lens that acknowledges how their cultural beliefs, values, and ways of living represent only one of many possible and acceptable ways of living.

The stages of denial, defence, minimization, acceptance, adaptation, and integration make up the continuum and predict a person’s journey towards intercultural competency. Along the continuum, the perceptions and experiences of difference become more and more complex until we can experience another’s culture with the same amount of complexity as our own.

As its name suggests, the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity develops an individual’s ability to have a more complex experience of otherness and constitutes what Bennett termed “intercultural sensitivity.” Intercultural competence is this ability to make meaning in other cultural contexts as comfortably as we do in our own culture.

Introduction to Bennett’s Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (Video)

Dally, J. (2013, September 28). Bennett’s Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/6vKRFH2Wm6Y

Stages of Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS )

Ethnocentric Stages of Development

(Summarized from Bennett, 2004, pp. 62–72; Bennett, 2017, pp. 3–5)

Ethnorelative Stages of Development

(Summarized from Bennett, 2004, pp. 62–72; Bennett, 2017, pp. 3–5)

A Few Important Final Notes on the DMIS

It would be incorrect to assume that those who are more interculturally sensitive are better people (Bennett, 2004, p. 9). The model describes not what it means to be a good person, but what it means to be good at navigating differences and good at intercultural relations.

It is also important to note that the DMIS is not a model of required knowledge, attitudes, or skills. Any changes in knowledge, attitudes, or skills are considered reflections of changes in a person’s expanding worldview.

The DMIS is about having a mindset that allows you to use the cultural knowledge and skills you have gained (or are gaining). Having cultural knowledge and skills without an ethnorelative worldview that enables you to use them appropriately is of little use. The DMIS describes how a person’s mindset shifts, allowing them to have greater intercultural sensitivity, and as a result, greater intercultural competence.

“All we can say about more ethnorelative people is that they are better at experiencing cultural differences than are more ethnocentric people, and therefore, they are probably better at adapting to those differences in interaction. Perhaps you believe, as I do, that the world would be a better place if more people were ethnorelative” (Bennett, 2004, p. 9).

Learning Activity 5: DMIS Self-Assessment

- Recall the descriptions of the DMIS stages. Read through the statements below that could be representative of an individual at each stage. Keep in mind that each stage reflects our experience of difference. Being at a higher stage does not mean you are a better person, just as being at a lower stage does not mean you are a lesser person.

- Do you see yourself in any of the statements? Check off statements that apply or sound like you. What is it about these statements that makes you see yourself?

- Look to see where most of your checked statements are. Where would you place yourself on the continuum?

Adapted from Bennett, M. J. (1993). A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. https://www.idrinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/FILE_Documento_Bennett_DMIS_12pp_quotes_rev_2011.pdf

Using Intercultural Tools to Interpret Miscommunications

When a conversation or communication does not go as we anticipated, we naturally try to understand why by looking at that situation through our own lens. We apply our past personal experiences and knowledge to make sense of what happened. The problem lies in just that—the assumptions we make based on our own cultural experiences and knowledge.

The D.I.E. Model is helpful for identifying why we are responding in this way and guides us toward a more thorough understanding of a miscommunication from another person’s perspective.

There are three steps:

- Describe what happened. We are encouraged to focus on the observable facts of the incident.

- Interpret what happened. This is our interpretation and what we think about the event. It is vital to notice what emotions are present and how we might be personalizing the incident.

- Evaluate what happened. We are encouraged to consider how we feel (whether positive or negative) about the incident.

| Describe – Interpret – Evaluate |

|---|

| Description: What I see (only observed facts) |

| Interpretation: What I think about what I see |

| Evaluation: How I feel about what I see (positive or negative) |

Applying the D.I.E. Model

Here is an example of how you might apply the D.I.E. Model to a typical settlement work scenario.

| What I see | What I think | What I feel |

| Description | Interpretation | Evaluation |

| My service user frequently interrupts me while I am speaking. They stop me with questions and other unrelated issues. These questions and comments often come with a raised voice. | The service user does not trust or value my knowledge, experience, and advice. They are not even listening to me. I know this based on their constant interruptions and bringing up unrelated issues. I hear frustration and anger in their voice. | I feel discouraged about this working relationship. This service user is an aggressive and difficult person who does not respect me and does not want to work with me. Working with this service user will be impossible. |

After working through the three steps, we consider some alternative explanations for the other person’s behaviour. The alternatives need only be possible; they do not need to be correct. This model prompts one to reserve judgement and seek an alternative understanding of the behaviour of others.

Some alternative explanations for this scenario include the following:

- The service user may come from a culture with different conversational patterns or rules for interrupting.

- The service user may come from a culture that does not have a linear thinking and communication style.

- The service user may come from a culture with a communication style that values expressiveness and conveys emotion.

- A raised voice may indicate excitement and passion rather than anger.

Learning Activity 6: Reflection

What other explanations of this scenario could be included?

Expanding Cultural Knowledge with Culture General Frameworks

What is the Difference Between a Stereotype and a Generalization?

A generalization is a cultural pattern that helps us to understand a culture (Ross, 2011). When we apply a pattern to a whole group as a rule and assume it must be true of everyone, it becomes a stereotype. Use generalizations not to assume, but to ask the right questions.

Cultural Generalizations

It is arguably impossible and quite unrealistic to become an expert in many different cultures. This is where culture generalizations and culture general frameworks can come in.

Developed by anthropologists and other experts in communication, these frameworks can give us an understanding of the big picture and identify some possible areas of difference between two cultures (Bennett, 2001, p.4). For shorter interactions, this sometimes can be enough to help avoid obvious misunderstandings. They can call attention to the most important differences that must first be considered when encountering someone of a different culture.

However, keep in mind that these frameworks are meant to be used as a starting point. Notably, the frameworks consist of generalizations that will not apply equally to every group member, even though they may help predict possible differences and when potential misunderstandings can arise. Consider the frameworks a hypothesis to be continually tested and verified on an ongoing basis.

Cultural Generalizations in Communication

Reflect on the following questions:

- How do you typically greet a friend? A co-worker? A service user?

- How do you know when it is your turn to speak in a conversation?

- How do you show interest in a conversation?

- How do you indicate understanding?

Language Use

The first notable cultural difference in communication is language. This has little to do with the language(s) we speak, but it is more about how language is used. Although differences may be subtle, they can be substantial. Language communicates greetings and identifies how turns are taken, how we interrupt, how we argue, how we criticize, and how we compliment one another (Bennett, 1998, p. 10).

For example, Meyer (2014) notes how silence can be a curious component of language use. Silence can indicate different things to different people; it could be indicative of irritation or misunderstanding. Americans are typically comfortable with two to three seconds of silence; in general, Americans have a “ping-pong” style of conversation and are not comfortable with either overlap or silence. On the other hand, Chinese people are comfortable with seven to eight seconds of silence. Therefore, from an American person’s perspective, the prolonged silence of a Chinese person might be assumed to mean they have nothing to add to the conversation. Conversely, the Chinese speaker may have difficulty adding to a conversation because they typically wait for a more extended period of silence before contributing and feel they cannot “jump” into the conversation.

Non-Verbal Behaviour

Differences in non-verbal behaviour refer to the use of voice (tone, pitch, etc.) and body language (facial expressions, gestures, distance or touch in communication). Like language use, these differences are generally unconscious and can be challenging to notice and explain.

As an example of non-verbal behaviour, we can talk about eye contact. As with language use, eye contact indicates turn-taking (Bennett, 2001, p. 6). For example, Americans tend to make medium-length eye contact before looking away. A longer, direct gaze indicates a desire for a change of speaker. In contrast, in some northern European countries such as the Netherlands or Germany, speakers use more prolonged and more direct eye contact and look away to indicate a change of speaker.

Americans tend to interpret prolonged eye contact as aggressive, whereas Germans tend to interpret weak eye contact as lack of interest. This might lead a German to intensify eye contact and an American to reduce eye contact to lessen the perceived threat. Both parties are thus left feeling that the other was trying to dominate the conversation.

In addition, the meaning of eye contact differs from culture to culture. In North America, sustained eye contact typically indicates attentiveness and that the listener is engaged in the speech. Lack of eye contact could indicate disinterest, boredom, or, at worst, dishonesty in speech. In many Asian cultures, however, direct eye contact is considered disrespectful.

Communication Styles

Video – Low Context vs. High Context Societies – Erin Meyer (4:05 )

The Lavin Agency Speakers Bureau. (2014, May 9). Leadership speaker Erin Meyer: Low context vs. high context societies [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/9oYfhTC9lIQ

Edward T. Hall (1976) is credited with observing and then coining the terms “high context” and “low context” communication styles.

High context cultures take significant meaning from the context or situation at hand rather than what is actually said (Bennett, 2001; Meyer, 2014). There is much “reading between the lines” that occurs, despite what is said or not said. Speakers in high context cultures tend to assume a large body of shared references. Communication is implicit, layered, nuanced, and sophisticated. In other words, it is not what is said but what is meant. In high context cultures, the listener does much of the work to decipher the message.

On the other hand, low context cultures pay little attention to the context but focus instead on what is directly communicated to make meaning. Communication in low context cultures tends to be explicit, simple, and straightforward. North American–style presentations are a fitting example of low context communication (Meyer, 2014). Students are taught a structured format for presentations from a young age that includes an introduction, body, and conclusion. The speaker starts by telling you what they will tell you. Then they tell you. And then they conclude by telling you what they told you. This exemplifies how in low context cultures the responsibility is on the speaker to ensure that the meaning of their message is communicated clearly.

Although speakers from high context and low context cultures can be talkative or quieter, the real difference is in how meaning is made. Many Western countries, like Canada, are more low context. On the other end of the spectrum, many African and Asian countries are high context.

As might be expected, differences in this particular communication style can result in considerable misunderstandings and miscommunications. As Meyer (2014) explained, low context people may perceive high context people as being secretive and lacking transparency. In contrast, high context people might believe that their intelligence is being insulted and may feel condescension.

When working with low context people, try to be as explicit as possible by putting things into writing and repeating key points. When working with a high context person, try to avoid repetition but instead ask questions to clarify as needed. Work on your ability to “read between the lines.”

As a settlement worker, you may find someone from a high context culture less likely to make a direct request for what they need. An individual from a high context culture could also become somewhat frustrated by another’s inability to “read the air” and perceived thoughtlessness.

Cultural Values

Hofstede’s 6 Dimensions Model of National Culture

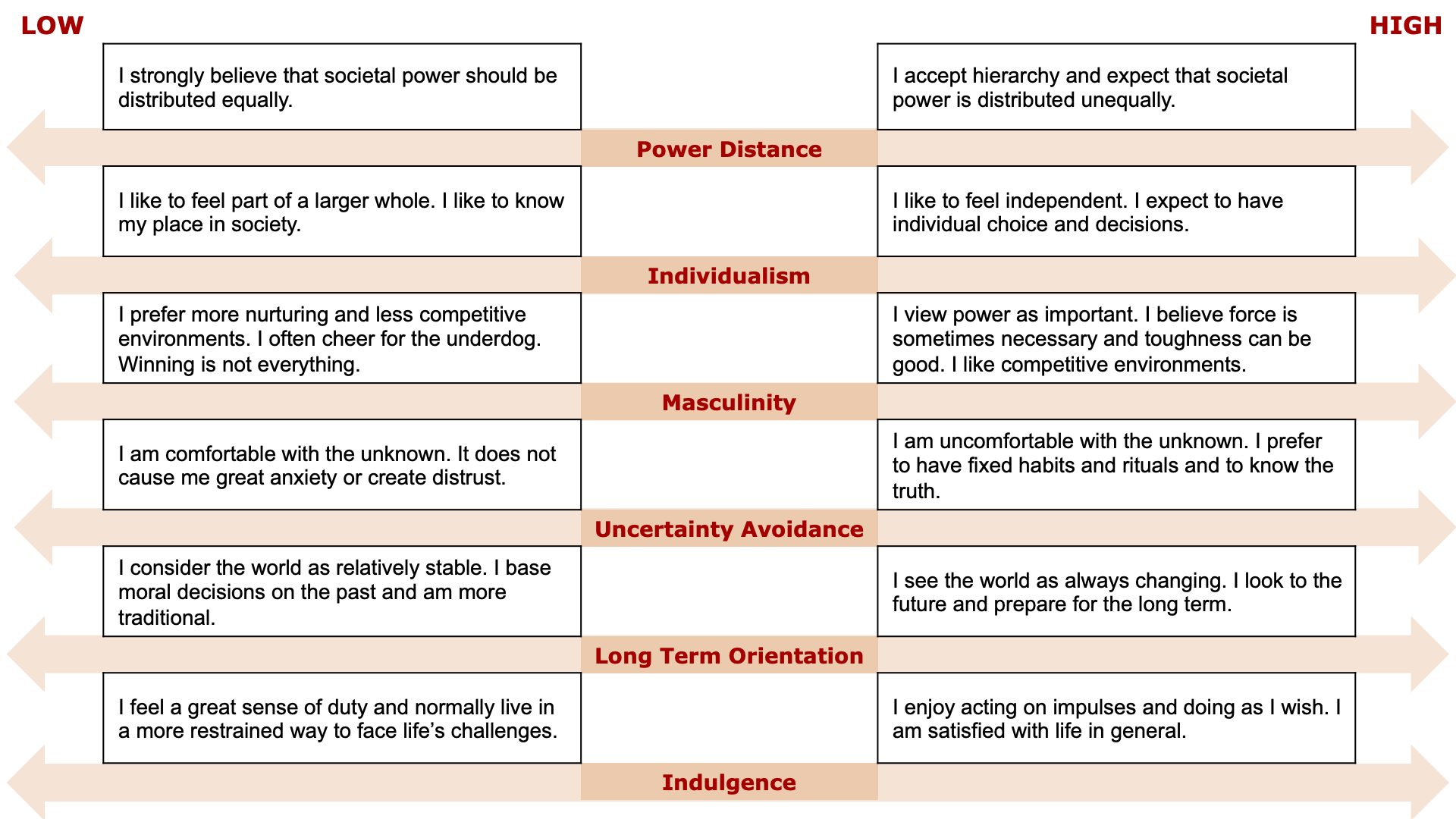

Culture value frameworks are among the more abstract of the culture general concepts. Although numerous frameworks have been developed over time, Hofstede’s Model of National Culture (1980, 2010) remains one of the best-known intercultural frameworks to date and has inspired many other frameworks since its inception in 1980.

Between 1967 and 1973, Professor Geert Hofstede surveyed IBM employees in more than 70 countries about their values and preferences in life (Bennett, 1998, p. 43). From this research, Hofstede created a model that initially included four dimensions of national culture—power distance, individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance. Hofstede’s model ranks and scores countries on each of the dimensions. With subsequent research, the value dimensions of long-term orientation and indulgence were later added. Hofstede listed cultural dimensions for 76 countries based on replicating and extending his original IBM study, which has subsequently been completed on various international populations and by other scholars.

Many contemporary studies of cultural values now, at least in part, use Hofstede’s categories. As with other culture general frameworks, Hofstede’s model contains cultural generalizations that cannot be assumed to apply to all individuals. In fact, differences between two individuals within a country’s culture could be just as significant as those between two individuals from two different countries. Furthermore, Hofstede’s dimensions are meant to be used as a point of comparison because scores are relative and only hold meaning when compared to another country’s scores.

What follows is a brief description of each of Hofstede’s six cultural dimensions.

Adapted from Hofstede, G. (n.d.). The 6-D Model of national culture. https://geerthofstede.com/culture-geert-hofstede-gert-jan-hofstede/6d-model-of-national-culture/

Learning Activity 7: Plot Yourself in the Six Dimensions

Choose a country of origin for a selected group of settlement service users you expect to work with in the future.

Go to Hofstede Insights: Country Comparison website

Compare that country to Canada on the six dimensions of national culture.

- Based on your self-reflection, are there cultural dimensions where your preference differs from the Canadian cultural profile?

- In what dimensions did the country you chose differ most from Canada?

- How do you expect these differences to affect a working relationship you would have with this service user?

- How can this help you be a more effective settlement professional?

Learning Activity 9: Apply your Knowledge – Using the D.I.E. Model and General Cultural Knowledge

Think about a possible cultural miscommunication from your personal experience. Can you apply the D.I.E. Model to understand what happened from a different perspective? Consider what we have discussed about culture general frameworks (e.g., language use, non-verbal behaviour, communication styles).

| Describe – Interpret – Evaluate |

|---|

| Description: What I see (only observed facts) |

| Interpretation: What I think about what I see |

| Evaluation: How I feel about what I see (positive or negative) |

Copy the chart below into your textbook journal and complete the chart for the miscommunication from your personal experience.

- What are the facts of what happened?

- How did you interpret this incident?

- How did this incident make you feel?

| What I see | What I think | What I feel |

| Description | Interpretation | Evaluation |

|

|

A Process Model for Improving Our Intercultural Competence

In this chapter, we began by defining our idea of culture. We continued to explore our own cultures and how our life experiences have shaped our assumptions and beliefs. Our journey of self-awareness continued by examining how we personally see and understand difference through the DMIS. We added to our cultural knowledge through an introduction to some culture general frameworks. We added a tool to our intercultural toolbox with the D.I.E. Model. The work we have done up until now (and will continue to do in the future) can be framed within Deardorff’s Process Model of Intercultural Competence.

Deardorff’s model illustrates how intercultural competence begins at an individual level with an attitude of respect, openness, curiosity, and discovery (Deardorff, 2015, pp. 140–142). These prerequisite attitudes involve valuing other cultures, withholding judgement, and having the ability to tolerate ambiguity. With these attitudes, an individual can deepen their cultural self-awareness and broaden their objective and subjective cultural knowledge. Skills like listening, observing, evaluating, analyzing, interpreting, and relating to others with diverse worldviews use these acquired attitudes and knowledge. Intercultural competence results when these attitudes, knowledge, and skills are applied, and the outcomes may be internal or external. An internal outcome is what happens within an individual. It is marked by a shift in their frame of reference and means that an individual can adapt an ethnorelative view and demonstrate adaptability, flexibility, and empathy. An external outcome is observed in the individual’s intercultural interactions and is marked by an ability to interact effectively and appropriately in differing contexts or demonstrate successful intercultural competence.

Deardorff’s Process of Intercultural Competence

Review Deardorff’s Process Model of Intercultural Competence on page 143 of the article “21st Century Imperative: Integrating Intercultural Competence.” As we have learned, intercultural competence is a lifelong and continuing process. As we work, travel, and live in multicultural communities, we will constantly meet and interact with unique members of diverse cultural communities. Because intercultural competence does not develop without intention, let us look to the future and make a plan for continuing development of these competencies.

Making an Intercultural Competence Development Action Plan

As has been discussed, the process of developing intercultural competence is personal, reflective, and requires considerable effort and time. An intercultural competence development action plan can help focus our activities to meet this goal. As with most goals, having a timeline will help keep you on track. Consider how much time you can reasonably commit to this work on a weekly or monthly basis. An effective action plan will include activities that best suit how you like to learn, your interests, and your future goals.

When choosing intercultural exploratory activities, think back to your identity wheel. Are there parts of your cultural identity you want to explore further? Think about the different cultural groups that make up your community. Remember that cultural groups can be based on race, gender, sexuality, religion, or other traits. Are there any noticeable points of intercultural stress for you between your own culture and a different culture? Can you identify any gaps in your cultural knowledge?

Here is a short list of intercultural exploratory activities to inspire your intercultural development plan:

- Keep learning. Sign up for an educational course, workshop, lecture, or webinar that focuses on intercultural communication or related cultural topics of interest.

- Consider the arts. Watch a film or documentary. Attend an art exhibit or performance. Listen to music from different cultures. Be present at post-event discussions to explore the concepts presented and deepen your learning experience.

- Create a reading list. Select books, blogs, or articles related to social justice, race, class, gender, or ethnicity. Select works by authors with backgrounds different from your own. Select books that relate to past, current, or future intercultural settings that you have or will have. Books can be fiction or nonfiction. Many works of fiction can provide insights into the history and cultural norms of culturally diverse groups.

- Travel with intention either abroad or to communities different from your own. Visit places of cultural importance to different communities, such as historical sites and museums. When travelling, make an effort to experience how people from that cultural community live, interact, and relate with others.

- Participate in diversity and inclusion efforts in your workplace. Join employee resource groups and volunteer for work-related responsibilities that involve cultural bridging.

- Create an intercultural journal to reflect on your experiences and daily interactions with others. Focus on cultural similarities and differences that you notice in these interactions. Challenge yourself to focus on situations you have observed or participated in where you and others needed to understand cultural differences to respond appropriately.

Keep in mind that simply participating in activities alone is not enough to expand your intercultural competence. It is the thoughtful and intentional reflection on these cultural experiences that truly promotes development and growth. Use the learning opportunities to increase your cultural self-awareness as well as to acquire knowledge about different cultural perspectives.

Be curious. Put yourself in situations where you will meet others of different cultures. Listen to people’s stories. Ask questions about their cultural practices, customs, and worldviews.

Supporting Clients to Develop Intercultural Competence

Developing intercultural competence allows a person to communicate with others more effectively and appropriately in differing cultural settings. That said, although we cannot necessarily improve the intercultural competence of another person, we can use these concepts to better support service users and better understand someone else’s experience.

According to Bennett (2001), the general rule is “Whoever knows the most about the other culture does the most adapting” rather than “Whoever has the power to impose their culture, does” (p. 8). Therefore, it is on the settlement professional to adapt and navigate gaps as best they can.

A few suggestions for bridging intercultural gaps while working with a service user:

- Share openly and honestly about your experiences and journey of intercultural competence.

- Have conversations about cultural differences. Encourage the service user to reflect on their own identity and culture.

- Learn from individual service users about their culture and cultural preferences.

- Do your homework. Keep adding to your culture-specific knowledge while testing cultural generalizations.

- Help the service user learn about cultural differences relevant for successful integration by providing insights.

- Whenever possible, explain the “why” behind what you are doing or saying. It may help the service user to view a behaviour from another cultural lens and mitigate miscommunications and misunderstandings. It could look like this: “In Canada, we often do or say x because of y.”

- When appropriate, gently and without judgement draw attention to behaviours that might cause issues in Canada because of cultural differences. Explain how that behaviour might be interpreted in Canada. It could look like this: “In Canada, when someone says or does x, it might be interpreted as y.”

- Remember to be patient, flexible, and adaptable.

Learning Activity 10: Reflection

As a settlement worker, what specific strategies might you use to bridge intercultural gaps with service users?

Review Activities – DMIS Stages

Key Characteristics Activity

Drag and drop to label stages based on a key descriptor.

Challenge Tasks Activity

Drag and drop to label stages based on a challenge task.

Reflection

Consider the DMIS stages and the challenge for each of the following:

- What kind of challenges might a service user in denial have when settling in Canada? What strategies could you use to support them?

- What kind of challenges might a service user in defence have when settling in Canada? What strategies could you use to support them?

- What kind of challenges might a service user in minimization have when settling in Canada? What strategies could you use to support them?

Image Credits (images are listed in order of appearance)

Bennett, M. J. (2014). A developmental approach to training for intercultural sensitivity. https://www.idrinstitute.org/dmis/

Self-Awareness Activity chart has been adapted from information on the following webpage: The 6-D model of national culture, by G. Hofstede, n.d. https://geerthofstede.com/culture-geert-hofstede-gert-jan-hofstede/6d-model-of-national-culture/