Chapter 5: Intercultural Competence and Communication

What is Culture and Intercultural Competence?

What is Culture?

This chapter explores the development of intercultural competence and communication. As a starting place, let us consider the following:

What is culture? How would you define culture?

|

Introducing Dr. Milton James Bennett Dr. Milton James Bennett is an American sociologist and leader in the field of intercultural studies. In the late 1970s, Dr. Bennett travelled to Micronesia to volunteer with the U.S. Peace Corps. He later returned to the United States to complete his doctorate in intercultural communication and sociology. Dr. Bennett was a professor at Portland State University in Oregon, where he established their graduate program in intercultural communication. It was also there in 1986 that he founded the Intercultural Communication Institute (ICI), now the IDR Institute, a non-profit educational foundation. He is recognized for his Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS), which is used in intercultural training programs in many countries. Dr. Bennett is the author of several books and many articles on intercultural competence and global leadership. Currently, he is an adjunct professor of intercultural studies in Italy and teaches graduate programs in Switzerland, Austria, and China. Dr. Bennett continues to create and deliver domestic and international diversity programs for various corporations, universities, and other organizations. |

When you hear the word “culture,” what do you think about? Culture is an umbrella term that is used in a lot of different contexts. Almost every day, we hear about trends and fads in popular culture and the media. In the business world, companies pride themselves on having a unique corporate culture. We might describe a sophisticated friend who has an appreciation for beauty and the finer things in life as being very “cultured.”

For our exploration, culture can be thought of as “the learned and shared values, beliefs, and behaviours of a community of interacting people” (Bennett, 2001, p. 1). Culture includes language, food, dress, music, arts, literature, and the group’s customs, beliefs, attitudes, and values.

Cultural groups can include ethnic, religious, or social communities, to name a few. Bennett (2004) further defined possible cultural groups explaining that

“the traditional definition of culture allows us to consider many of the well-known groups defined in diversity work as cultures, including those based on nationality, ethnicity, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation, economic status, education, profession, religion, organization, and any other differences learned and shared by a group of interacting people” (p. 2).

This broad definition of cultural groups suggests just how complex our cultural identities are.

Culture and Identity

Any discussion or exploration of culture must recognize that culture significantly influences personal identity. Like culture, the term “identity” is commonly used in various contexts but means different things to different people. Because the word is used so often, many people assume that others know what they mean when they use the word. A proper definition that captures the actual complexities of the concept has never really been agreed upon (Fearon, 1999, p. 35).

In the late 1950s, Erik Erikson started the conversation on identity, and his definition of identity is still the most relevant and accepted today (Fearon, 1999, p. 35). Erikson is a German American psychologist known for his theory on human psychological development and for coining the term “identity crisis” (Schaetti, 2000, p. 5). Erikson broadly defined identity as an essential self-organizing principle that evolves throughout our lives. Further, he argued that identity gives us a sense of stability within ourselves and when interacting with others. It allows people to differentiate themselves from others and to act uniquely and independently.

Bonny Norton (1997), a leader in the field of identity and language learning, defines identity as “how people understand their relationship to the world, how that relationship is constructed across time and space, and how people understand their possibilities for the future” (p. 410).

While Erikson’s definition of identity focuses on the internal dynamic, Norton’s definition draws attention to the external ways in which our identity is shaped. Both definitions, however, emphasize the relational nature of identity; identity is about how we view ourselves in relation to others and the world around us.

Learning Activity 1: Reflection – Analogies for Culture

The images above represent ways culture can be thought about or viewed. Like the water to the fish in the fishbowl, the influence of our own culture is often not apparent to us. Eyeglasses represent the fact that we all wear our own cultural lenses when interpreting an event or situation. In the same way an onion has layers to be peeled back, layers of culture shape people. Understanding an individual requires peeling back the layers.

To sum up, these analogies give us insight into our own worldview and how the cultural lens through which we see the world is often invisible to us. Importantly, every individual has unique life experiences and a cultural identity shaped from and layered by their membership in numerous communities. It is an understanding of and appreciation for the complexity of an individual’s culture that is a beginning place for the development of intercultural competence.

Objective and Subjective Culture

Edward T. Hall’s (1976) Iceberg Model of culture is valuable for understanding the nuanced components of culture. If you have ever seen an iceberg, you will know that only a tiny portion of the iceberg is visible from the surface. Much of the iceberg exists under the surface.

Hall’s Iceberg Model aptly makes the comparison to how culture works, and indeed, culture can be thought of like an iceberg. It is relatively easy to observe and learn many superficial aspects of culture such as language, traditional dress, foods, and music. It is much more challenging to observe and understand cultural elements that are not visible from the surface. These hidden facets of cultures, which influence core values and behaviours, are only revealed upon deeper examination over time.

Hall’s Cultural Iceberg Video

Watch the video (1:30 min) below to learn more about Hall’s Iceberg Model.

GCPE BCGov. (2016, April 20). Cultural iceberg [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/woP0v-2nJCU

Adding to the iceberg analogy, Bennett (1998) refers to the two aspects of culture as big “C” and small “c” culture (p. 2). Big “C” Culture encompasses the institutions of society, including features such as art, literature, drama, music, and dance. It also consists of what would be commonly studied or included in a history course, features such as social, economic, political, and linguistic systems. Big “C” Culture is the more objective culture, or the top of Hall’s Iceberg Model. To Bennett, small “c” culture, on the other hand, is the less obvious. It is the day-to-day thinking and behaviour of a group of people—the learned and shared patterns resulting from groups of interacting people. It is how our values are determined and manifest themselves. Small “c” culture is the more subjective culture comparable to the bottom of Hall’s Iceberg Model.

Although understanding a lot about big “c” Culture, or objective culture, creates knowledge, it does not necessarily mean we can communicate well with a person of that culture. In other words, this type of knowledge alone does not equate to intercultural competence. When we consider developing and maintaining relations, understanding small “c” culture (the invisible part of the iceberg) is critical. We need to understand the beliefs, behaviours, and values of a group. As Bennett (2001) reminds us, “It is this type of subjective culture that allows us insight into the worldview of another rather than a more superficial understanding” (p. 2).

Learning Activity 2: Reflection – Working Across Cultures

What insights do the culture analogies give us about working across cultures effectively?

What is Intercultural Competence?

Below, Figure 1 illustrates the meaning of three key terms: multicultural, cross-cultural, and intercultural. Based on these images, how would you differentiate the three concepts?

Canada is well known and recognized for being a multicultural country. Yet, what does that mean, and is being multicultural enough? Schriefer (2016) defined a multicultural society as consisting of people from various cultures or ethnic groups. Being multicultural does not, however, mean that there is meaningful interaction between these different communities.

Differences may be appreciated and recognized in a cross-cultural society, but any change in interactions is on an individual level instead of societal change. Other groups are compared to the dominant culture, which is the standard, or “norm.”

Intercultural societies show deep comprehension and respect for differences. Members of an intercultural society learn and grow from one another. Interactions within the society lead to the mutual exchange of ideas and norms to build deeper relationships. In an intercultural society, no one is left unchanged.

Learning Activity 3: Reflection – Cultural Mindsets

- How might a multicultural mindset affect settlement work?

- How might a cross-cultural mindset affect settlement work?

- How might an intercultural mindset affect settlement work?

Now that we have defined our understanding of culture and intercultural societies, what does it mean to be interculturally competent? Intercultural competence is generally accepted as the ability to interact effectively and appropriately across different cultures (Bennett, 2014, p. 4). The term “intercultural” suggests an ability to go between or among cultures, while “competence” suggests the ability to be effective and appropriate.

According to Bennett (2014), there are three components of intercultural competence—cognitive, affective, and behavioural (p. 5). From an intellectual standpoint, the most essential cognitive competency is our cultural self-awareness. It is difficult to appreciate the worldview of others without first becoming aware of our own cultural worldview. The most crucial affective competence is curiosity about other cultures. Part of intercultural competence is indeed learning about other cultures—both the superficial as well as the more profound ideas of the culture. Finally, according to Bennett, the most critical behavioural competency is empathy. Importantly, empathy in the context of intercultural competence is not the ability to see ourselves in another’s shoes, but the ability to see the world from another’s worldview.

“Cultural self-awareness refers to our recognition of the cultural patterns that have influenced our identities and that are reflected in the various culture groups to which we belong, always acknowledging the dynamic nature of both culture and identity.”

(Bennett, 2014, p. 5)

From Bennett’s competencies, we can see that intercultural competence is much more than a technical skill set to learn, but a mindset to embody. Furthermore, it begins which cultural self-awareness, which leads us to our first activity.

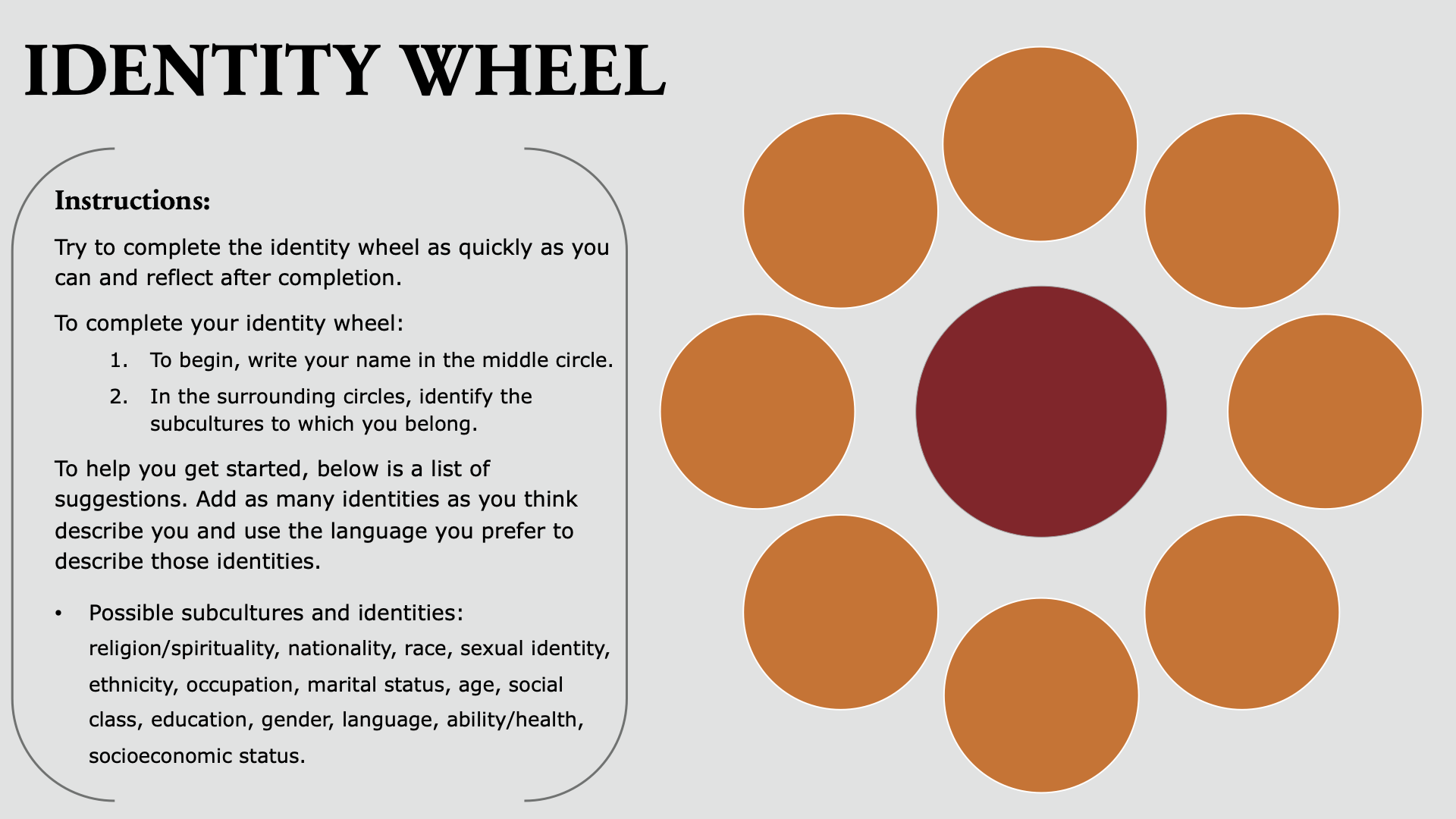

Learning Activity 4: Cultural Self-Awareness – The Identity Wheel

Intercultural competence is an intentional process. Before attempting to understand our interactions in intercultural settings, it is crucial as settlement professionals that we first have a clearer view of how our own culture has shaped our identity and the lens we use to see the world.

As we start thinking about our own personal cultural identity, creating an identity wheel is a valuable reflective exercise. As previously discussed, identity is how we see ourselves in relation to the world. It is the characteristics and roles that make us recognizable as members of cultural groups. Because we all belong to numerous cultural groups, we possess numerous identities. These groups or cultures in which we exist and which shape our identities make up the identity wheel. The goal of this activity is to identify the various cultures or subcultures that mould our identity.

Instructions

Access a PDF version of the Identity Wheel that you can edit to complete this activity here.

Post-Activity Reflection

- Which identity did you write first?

- Are there any identities that you had not thought of before today? Why do you think that is?

- Which aspects of your identity feel especially meaningful to you and why? Which aspects feel less meaningful to you and why?

- What identities have the most substantial effect on how you perceive yourself? On how others perceive you?

- Are there identities you would like to learn more about?

- How did it feel to define yourself this way?

Image Credits (images are listed in order of appearance)

A30Y5W by KoiQuestion, CC BY-SA 2.0

Eyeglasses by Kent Landerholm, CC BY-SA 2.0

Mixed onions by Colin, CC BY-SA 3.0

Schneider, S., & Heinecke, L. (2019). The need to transform science communication from being multicultural via cross-cultural to intercultural. Advances in Geosciences, 46, 11–19. DOI: 10.5194/adgeo-46-11-2019

Self-awareness by Guian Bolisay, CC BY 2.0 Generic licence