Module 2: Creating a Course Syllabus and Structure for Online Teaching (Light)

The light version of this module is designed to assist you in building community and student engagement in your online course.

Welcome to the module, Creating a Course Syllabus and Structure for Online Teaching. This module will focus on the course syllabus and its role in ensuring both instructors and students understand their roles, responsibilities, and expectations (academic and social) during the delivery of the course. The following material will outline both the required (we have an academic policy that identifies required information for a course syllabus here at the University of Lethbridge) and suggested contents of a course syllabus, as well as a variety of examples and ideas to consider when designing and delivering a course in a fully-online delivery model.

Welcome to the module, Creating a Course Syllabus and Structure for Online Teaching. This module will focus on the course syllabus and its role in ensuring both instructors and students understand their roles, responsibilities, and expectations (academic and social) during the delivery of the course. The following material will outline both the required (we have an academic policy that identifies required information for a course syllabus here at the University of Lethbridge) and suggested contents of a course syllabus, as well as a variety of examples and ideas to consider when designing and delivering a course in a fully-online delivery model. Please note: If you would like feedback on your activity, please post it to the general discussion forum for peer feedback. Otherwise, there is no expectation that you complete the activity designed in this module.

If you want to delve deeper into the topic, you can access the comprehensive module with additional activities and resources here.

Instructions:

- Read through the guiding questions.

- Section 1: Essential Elements

- Discover what the U of L identifies as required components of the course syllabus

- Section 2: Other Items to Consider

- Examine other possible items you could include in your syllabus

- Section 3: Crafting Course Outcomes

- Learn about what course outcomes are and how to create them

- Section 4: Designing for Online Delivery

- Examine some different aspects to consider when presenting your material and resources online for your students

- Section 5: Sample Activity

- Share all or a portion of your course syllabus with the group via our Moodle sharing area for feedback

- Section 1: Essential Elements

Time: Depending on your level of engagement, this module should take approximately 2-3 hours.

- What are the University of Lethbridge essential course syllabus elements?

- What are some of the optional elements that could/should be considered including?

- What needs to be considered when creating a course syllabus for online delivery vs or face-to-face (F2F)?

- What are the things that need to be considered in order to ensure that the course syllabus (and subsequent activities and assessments) are accessible to all students?

- How do I need to structure the course content in order to ensure a cohesive learning experience for my students?

Section 1: Essential Elements

The course syllabus is both a central guiding document for any course as well as a contract between yourself (as the instructor) and your students. As such, the course outline needs to include enough information for our students to know what to expect from our course while also ensuring they understand expectations (for delivery and assessment) for the upcoming term.

The University of Lethbridge has two policy documents (Assessment of Student Learning Policy and Procedures – Undergraduate Students and Assessment of Student Learning Policy and Procedures – Graduate Students) that outline requirements for a course syllabus. You may choose to link to these directly in your syllabus.

These policies clearly outline required information. The statements (pg. 2) in the grey boxes are taken directly from the policy:

1.2 The course outline includes the following essential elements:

1.2.1 The instructor’s name and contact information, course number, section and title, and the Department, Faculty or School.

1.2.2. Where, when, and how students may seek assistance from the instructor.

Clear lines of communication are vital in any classroom, but in an online classroom, it is essential that the methods of communication are both accessible and reliable (for both student and instructor). No matter what communication methods you use, test them out with your students to ensure that everyone is able to contact you via these methods BEFORE they need to.

1.2.3. A list of required reading materials, supplies, and expenses for events outside of regular classes, and, where the instructor requires the study of material that cannot be specified at the outset of the course, and explicit statement to that effect.

1.2.4. Relative weights of all work used to determine a final grade. Where attendance or other forms of class participation are required, the criteria for these measures should be explicitly stated.

1.2.5. How the final letter grade for the course will be determined if percentages are used.

1.2.6. Due dates, approximate due dates, or the approximate frequency of graded work.

1.2.7. Penalties for late work, if appropriate.

1.2.8. A reminder that students in the course are subject to the student discipline policy for academic offences (undergraduate) or student discipline policy for academic offences (graduate) and student discipline policy for non-academic offences in accordance with the policies.

1.2.9. If instructors use a University-approved plagiarism detection service to determine the originality of student papers, notice must be provided in the course outline. Student work may be stored in the database of the service, and if students object to such storage, they must advise the instructor in sufficient time that other techniques may be used to confirm the integrity of written work.

The final entry in this section of the document speaks directly to the contractual nature of the course syllabus. Many people erroneously believe that once the course outline is passed out to the class, it is set in stone. This is not the case. There is language in our policies to allow for modification of the course outline – as long as it is in the best interest of the students – and should be done in consultation with students. This statement may even be included in your course syllabus (if you choose), so that it is clear that modifications can be made under certain situations if they are in the best interest of the students. That final passage states that:

Section 2: Other Items to Consider

Outside of the required components that are defined by the Assessment of Student Learning Policy and Procedures, there are a number of items that are well worth considering including. These items include the following:

- A territorial acknowledgment

- Liberal Education statement

- Student accommodation statement

- Technical Requirements for the course statement

- Communications expectations statement

The University of Lethbridge has a long-standing relationship with the Blackfoot Confederacy. The formation of the Iikaisskini (ee-GUS-ganee) Gathering Place on campus is meant to be a gathering place for all on campus to share stories, teachings, and wisdom. The name Iikaisskini means “low horn” and is named in honor of Leroy Little Bear (BA, JD, HON. DAS, HON. LL.D) and his tireless service to the University. To help acknowledge and welcome our Indigenous students into our classrooms, a territorial acknowledgment statement has been written for both our main campus in Lethbridge, as well as a dedicated version for our Calgary campus. This statement highlights our ties to the Indigenous peoples and land that our campuses inhabit, and their inclusion helps to remind all of our students of this connection. A short form of the statement that would be appropriate (for the main campus) for inclusion might be:

A version for our Calgary campus might be:

The most current acknowledgment statements can be located here – https://www.uleth.ca/sites/default/files/2019/08/final_territorial_statements_june_2019.pdf

The University of Lethbridge was founded on the principles of Liberal Education. With the recent revitalization of this foundation and the formation of the School of Liberal Education (2017), inclusion of a Liberal Education statement might be helpful for your students. Here is a sample (written by the School of Liberal Education) of a statement that you might want to consider including:

Liberal education has been a community tradition at the University of Lethbridge since its founding. Our principle of Liberal Education is based on four pillars:

- Encouraging breadth of knowledge

- Facilitating connections across disciplines

- Developing critical thinking skills so that our graduates can adapt to ever-changing employment and social conditions

- Emphasizing engaged citizenship in our communities at all levels from the local to the global

More information about our School of Liberal Education can be found here – https://www.uleth.ca/liberal-education

Student Accommodations Statement:

The University of Lethbridge has a very clear policy on Academic Accommodations of Learning for Students with Disabilities. In addition, the Accommodated Learning Centre has a wealth of information (for both Faculty and Students). Including a brief statement acknowledging that your classroom is an accommodating environment will also help those students who require accommodation feel more welcome and included. This statement might look something like this:

In addition to the needs of students who have an identified disability, paying attention to when designing your course material and activities can be very beneficial to ALL of your students. We will spend more time discussing Universal Design for Learning in the Comprehensive version, Option 3: Designing for Online Delivery.

Technical Requirements of the Course:

Normally, students require little beyond the required textbook and the ability to make their way to class regularly in order to participate in a face-to-face class. Moving to online delivery brings with it other requirements that should be clearly communicated in the course outline for students. This means thinking about the types of activities you intend to engage the students in (and what is going to be required to participate in those activities). Some questions to consider include the following:

- Will you be holding synchronous (real-time) lectures?

- What platform will you be utilizing to conduct these lectures?

- Will that platform work on a cell phone, a tablet, older computers?

- How fast of an internet connection will be required in order to participate in this type of lecture?

- What types of activities will you be asking the students to engage in?

- Will additional software be required in order to engage in these activities?

- Will students require library access to complete activities/assignments?

A sample technical requirements statement could look something like the following:

![]() Additional statements may be needed to allow for the design of your course and the activities/assignments in which you will be engaging students. For example, if you are making use of an external interactive tool to engage students, you will want to include a sentence that identifies this tool and any registration or downloads that need to be performed in order to make use of that tool.

Additional statements may be needed to allow for the design of your course and the activities/assignments in which you will be engaging students. For example, if you are making use of an external interactive tool to engage students, you will want to include a sentence that identifies this tool and any registration or downloads that need to be performed in order to make use of that tool.

Communication in an online course is absolutely vital to ensure student engagement and ultimately success. Creating clear lines of communication are very important but just as important are the guidelines and expectations for those lines of communication. Creating multiple pathways for communication to take place (both between student and instructor as well as student to student) encourages students to engage in the course and material. The use of email, discussion forums, and online office hours are all methods to help make yourself more accessible to students.

Some things to consider are the expectations associated with each of these forms of communication. For example, if you are encouraging the use of email, you may consider the following:

- How long should they expect to wait for a response?

- Do you have times of the day that you dedicate to checking and responding to emails?

- What information do you need in an email to ensure that you are able to quickly answer the question (course title, section, assignment)?

If you are utilizing discussion forums, here are some additional considerations:

- What is the etiquette that you want them to observe in discussions with each other?

- What is an appropriate question for this forum and what should be handled in a more personal and direct manner?

- How often should students be checking a forum like this to address questions?

- Is participation in this type of forum tied to marks in the course?

A great infographic to help outline 15 Rules of Netiquette for Online Discussion Boards can be found here. (Online Education for Higher Ed – Touro College).

If you are going to make use of online office hours, consider the following:

- How will you manage multiple students who want to meet with you at the same time?

- What platform are you going to use for this?

- Will that platform be a barrier for your students?

Section 3: Crafting Course Outcomes

A great deal has been written about what a learning outcome (Bloom, 1956; Allan, 1996; Hussey & Smith, 2002) is as well as the difference between a learning outcome and a course objective. Unfortunately, there is not a great deal of consistency with the use of language when it comes to outcomes vs objectives or even goals. For the purpose of this resource (and the work that we do at the Teaching Centre), we are going to use the following definitions to describe the terms goals, objectives and learning outcomes (as identified by the Undergraduate Education and Academic Planning group at San Francisco State University)

This section gives you the opportunity to craft your own course outcomes as you work through the following topics:

- Define goals, objectives, and outcomes

- Examine learning taxonomies

- Gain practice writing learning outcomes

- Additional resources

Goal – A goal is a broad definition of student competence. Examples of these goals include:

- Students will be competent in critical questioning and analysis.

- Students will have an appreciation of the necessity and difficulty of making ethical choices.

- Students will know how to make connections among apparently disparate forms of knowledge.

Objective – A course objective describes what a faculty member will cover in a course. They are generally less broad that goals and broader than student learning outcomes. Examples of objectives include:

- Students will gain an understanding of the historical origins of art history.

- Students will read and analyze seminal works in 20th Century American literature.

- Students will study the major U.S. regulatory agencies.

A few key points:

- Course objectives are often a description of what the Faculty member/instructor will cover in the course

- Learning outcomes are student-focused and written in such a way that they are measurable/observable

- Identify the most frequently encountered endings for nouns, adjectives and verbs, as well as some of the more complicated points of grammar, such as an aspect of the verb

- Read basic material relating to current affairs using appropriate reference works, where necessary.

- Make themselves understood in basic everyday communicative situations.

*retrieved from https://ueap.sfsu.edu/sites/default/files/assets/docs/student_learning_outcomes.pdf April 3rd, 2020.

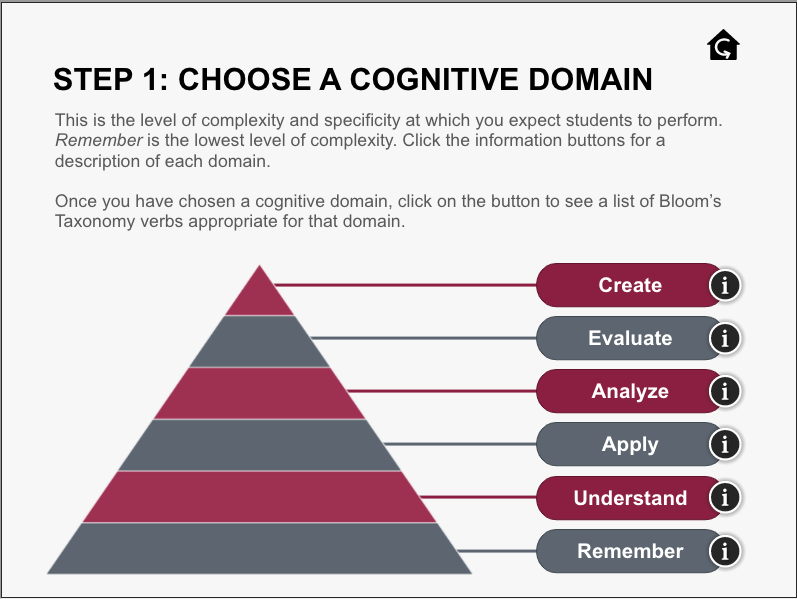

To write learning outcomes, we need to understand not only what we want our students to be able to demonstrate upon completion, but at which level we expect them to be able to complete it. Accordingly, we need a common language to identify possible levels of understanding. There are several educational taxonomies that will help us to find the language necessary to write these outcomes.

Here is a graphic that illustrates both the original Bloom’s Taxonomy and the revised version of 2000:

There are several other taxonomies that might be of interest when thinking about how learning objectives can be written/framed. Some of the other prominent taxonomies are:

- The Six Facets of Understanding by Wiggins and McTighe (1998) – discussed in detail in their Understanding by Design book. Here is a link to a whitepaper published by the ASCD.

- The SOLO (Structure of Observed Learning Outcomes) taxonomy by Biggs and Collis (1982) – outlined in their book Evaluating the quality of learning: the SOLO taxonomy (structure of the observed learning outcome). Here is a link to an overview of the SOLO taxonomy created by Future Learn.

- The Taxonomy of Significant Learning by Fink (2003) – published in his book Creating Significant Learning Experiences. Here is a link to an overview of the Taxonomy of Significant Learning put together by the Peak Performance Centre.

The process of writing learning outcomes then becomes a matter of matching the level of skill/understanding that you expect your students to demonstrate with a specific area of understanding and how you will expect them to be able to demonstrate this to you (and themselves). There are many resources that can be extremely helpful in writing outcomes, but probably one of the easiest to use (and most visual) is this one by Arizona State University.

By following the steps in their outcome (they use the term objective) builder, you can quickly write learner-centred outcomes for your class.

The following additional resources may be of interest but are not required:

- Constructing a Course Outline or Syllabus (Teaching Centre, University of Lethbridge)

- Foundations of a Course Outline Template (Ryerson University)

- List of Measurable Verbs used to Assess Learning Outcomes (Clinton Community College)

- Blooms Taxonomy of Measurable Verbs (PDF) (Utica College)

Section 4: Designing for Online Delivery

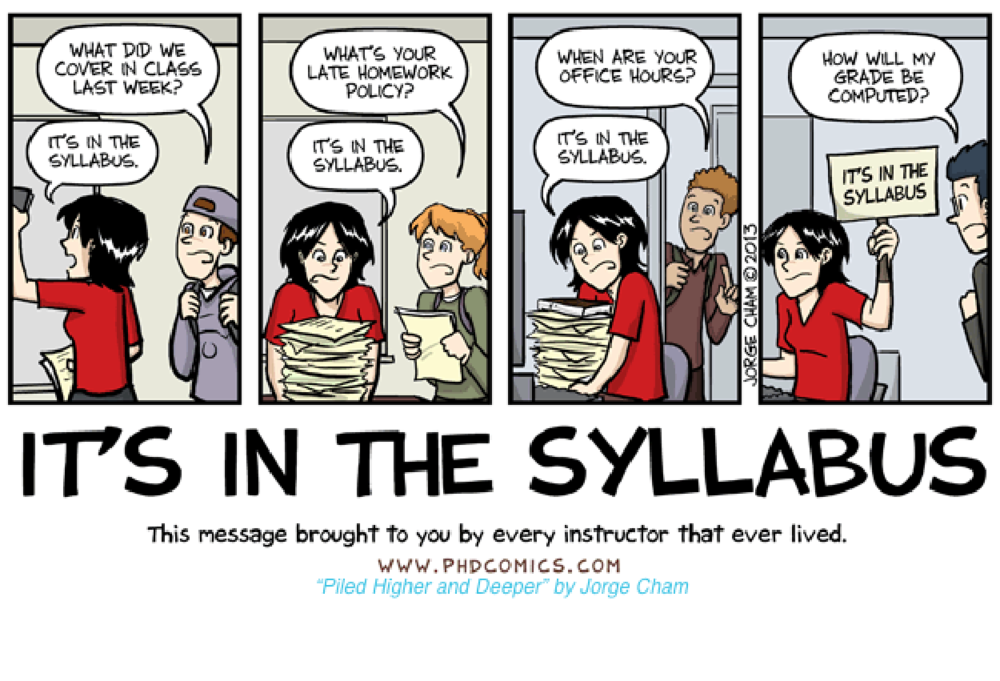

Whether you create your course syllabus as the starting point for designing your online course or after you have created the structure of the course, it is important to understand that the syllabus is the entry point into your course. In many of our courses, we discuss the syllabus at the beginning of the course and then expect students to refer back to it throughout. But do they? How many student interactions go just like this:

To combat this unfortunate reality for many, consider turning your course syllabus into not only something more useful for students but also something that is referenced throughout your course (both directly and indirectly). Creating your course syllabus in such a way that you can link back to specific parts of it will help students remember the role it has in helping explain the structure of the course. The idea of creating a “warm” syllabus has been an idea that has been discussed in a number of articles written for the Association for Psychological Science. One such article titled Creating the Foundation for a Warm Classroom Climate (January, 2011), discusses the impact that the tone of the course syllabus can have on setting the tone for the entire course.

There are many different ways in which a course syllabus can be presented to students. How about considering a course syllabus that is laid out as a graphic organizer of sorts – with all of the key information presented on the first page in an easy to view layout. The Visual Communication Guy has an excellent tutorial on turning your syllabus into an infographic (Aug 14, 2017) that is worth reading if you are interested in going this route with your syllabus. Another example of this can be found here.

Another possibility is creating what Michelle Pacansky-Brock calls a Liquid Syllabus. A liquid syllabus is a version of your syllabus that is mobile-friendly (displays well on a mobile device). She writes about it in an article posted to the Teaching Without Walls website (Aug 13, 2014) and also summarizes her ideas in this brief YouTube video (2 minutes 48 seconds).

Designing an Online Course

Creating a well structured, inviting, and engaging learning experience for students is about much more than simply having engaging content. The entirety of the course — from the introduction of the course and materials to the course syllabus to the structure, design, and layout — contributes to the student learning experience (and to student success). Most often we are not creating course material from scratch for online delivery; rather, we are re-purposing material that was created for a face-to-face delivery online. This brings with it specific challenges and considerations:

- How will online delivery impact what/how I present to the students?

- How will working online impact the students’ ability to complete tasks?

- How will I engage students in their learning and with each other?

- How much time will these activities take in an online environment?

- How will I balance (real-time) vs interaction with the students?

In addition to these questions, we should also consider how we present this information to students.

A great deal has been written about how to design an effective online course (for a variety of audiences). An article title Designing Effective Online Courses: 10 Considerations (Burns, 2016) for the eLearning Industry outlines the following 10 key points. She indicates a good online course needs to have the following attributes:

- Grounded in an understanding of the learning process

- Based on the needs of the adult learners

- Links theory and practice

- Accommodates a wide range of learning styles

- Accessible to all

- Flexibly designed

- Flexibly delivered

- Provides for flexible assessment

- Utilizes a variety of media

- Promotes interactivity

An article titled 4 Expert Strategies for Designing an Online Course published to Inside Higher Ed (Rottmann & Rabidoux, 2017) outlines the following 4 strategies:

- Involve the learner – find ways to engage the students in the learning process. Find ways to get students interacting with the material (and each other) as part of the course.

- Make collaboration work – find ways to engage students in meaningful peer collaboration. Clear expectations and the time to engage with each other (as well as support for the tools being used) will help.

- Develop a clear, consistent structure – a well designed course draws the learner into the experience. A clearly laid out structure that is repeated from module/section to module/section helps. Breaking the material down into more manageable sections can help make it easier to work through for students.

- Reflect and revise – there are several models that can help gather feedback on the course and make revisions. The key is to be open to feedback – even seek it out from students.

These are great tips, but what does this look like within the confines of a course? What are some of the things that you can do within the University of Lethbridge Moodle environment that will help to create an inviting environment for the students? A few simple steps that can help make Moodle a bit more inviting for students are listed below:

- Use graphics (where appropriate) to help make the content a bit more visual (less text-heavy). The use of labels in Moodle can also be helpful to provide context and information around the activity and resource links.

- Use short video clips to help build community but to also help introduce topic sections or explain instructions. Support these with close captioning or a transcript of the video (for accessibility). These can help give the content more of a personal feel and help the students get to know you a bit.

- Break content sections into clear, manageable chunks for students.

- Be consistent with how you layout/present your material from section to section (so students quickly learn what to expect).

Examples

Here are a few samples from one of our FLOf course:

Ultimately, there is no “right” way to accomplish this. It comes down to what works for you (and your students), the content that you are presenting, and your approach to teaching. It often takes some experimentation to find an approach that works for you.

Additional Resources:

The following resources might help you get more familiar with some of the content that you can place into Moodle and some of the ways in which you can format content for a more inviting presentation to your students:

- Changing Topic Titles in Moodle (moodleanswers.com support site)

- Adding and Removing Sections in Moodle (moodleanswers.com support site)

- Embedding a YouTube Video in Moodle (moodleanswers.com support site)

- Building Custom Content in Moodle (moodleanswers.com support site)

Section 5: Sample Activity

We would like to encourage you to share all (or part) of the syllabus that you have been working on with the larger group OR ask questions about portions of your syllabus of the others in the course.

Sample activity: Course Syllabus

Time: Approximately 30 minutes

For this activity, you can take the course syllabus (all or part of) that you are working on and post it to the course discussion forum for feedback from others.

Instructions:

Step 1: Decide if you want to share the entire course syllabus or just a portion of it.

Step 2: Post your syllabus to our course discussion forum for feedback OR pose questions about the syllabus that you are working on and would like some input on.

Step 3: Spend a little bit of time taking a look at the syllabi or questions that others have posed and feel free to respond to a few.