6.4 Handling Conflict Better

Identifying Conflict Patterns

As mentioned, much of the research on conflict patterns has been done on couples in romantic relationships, but the concepts and findings are applicable to other types of relationships. So far in this chapter, we have already looked at some common causes of conflict and conflict management styles and behaviours. Next, we will look at four common triggers for conflict viewed from the perspective of oneself as the communicator and what can be done to avoid them in your own communication with others. The four common triggers for conflict are criticism, demand, cumulative annoyance, and rejection (Jacobson et al., 2000). We will discuss each of these and then strategies you can use to avoid them. These strategies can also be used to decrease, or resolve conflict, in other situations as well.

We all know from experience that criticism, or comments that evaluate another person’s personality, behaviour, appearance, or life choices, can lead to conflict. Comments do not have to be meant as criticism to be perceived as such. If Gary comes home from college for the weekend and his mom says, “Looks like you put on a few pounds,” she may view this as a statement of fact based on observation. Gary, however, may take the comment personally and respond negatively back to his mom, starting a conflict that will last for the rest of his visit. A simple but useful strategy to manage the trigger of criticism is to follow the old adage, “Think before you speak.” In many cases, there are alternative ways to phrase things so they are taken less personally, or we may determine that our comment doesn’t need to be spoken at all. The majority of the thoughts that we have about another person’s physical appearance, whether positive or negative, do not need to be verbalized. Ask yourself, “What is my motivation for making this comment?” and “Do I have anything to lose by not making this comment?” If your underlying reasons for asking are valid, perhaps there is another way to phrase your observation. If Gary’s mom is worried about his eating habits and health, she could wait until they’re eating dinner and ask him how he likes the food choices at school and what he usually eats.

Demands also frequently trigger conflict, especially if the demand is viewed as unfair or irrelevant. It’s important to note that demands rephrased as questions may still be perceived as demands. Tone of voice and context are important factors here. When you were younger, you may have asked a parent, teacher, or elder for something and heard back, “Ask nicely.” As with criticism, thinking before you speak and before you respond can help manage demands and minimize conflict. Demands are sometimes met with withdrawal rather than a verbal response. If you are doing the demanding, remember that a higher level of information exchange may make your demand clearer or more reasonable to the other person. If you are being demanded of, responding calmly and expressing your thoughts and feelings are likely more effective than withdrawing, which may escalate the conflict.

Cumulative annoyance is a building of frustration or anger that occurs over time, eventually resulting in a conflict interaction. For example, your friend shows up late to drive you to class three times in a row. You didn’t say anything the previous times, but on the third time you say, “You’re late again! If you can’t get here on time, I’ll find another way to get to class.” Cumulative annoyance can build up like a pressure cooker, and as it builds up, the intensity of the conflict also builds. Criticism and demands can also play into cumulative annoyance. We have all probably let critical or demanding comments slide, but if they continue, it becomes difficult to hold back, and most of us have a breaking point. The problem here is that all the other incidents come back to your mind as you confront the other person, which usually intensifies the conflict. You’ve likely been surprised when someone has blown up at you because of cumulative annoyance or when someone you have blown up at didn’t know there was a problem building. A good strategy for managing cumulative annoyance is to monitor your level of annoyance and occasionally let some steam out of the pressure cooker by processing through your frustration with a third party or directly addressing what is bothering you with the source.

No one likes the feeling of rejection. Rejection can lead to conflict when one person’s comments or behaviours are perceived as ignoring or invalidating the other person. Vulnerability is a component of any close relationship. When we care about someone, we verbally or nonverbally communicate. We may tell our best friend that we miss them or plan a home-cooked meal for our partner who is working late. The vulnerability that underlies these actions comes from the possibility that our relational partner will not notice or appreciate them. When someone feels exposed or rejected, they often respond with anger to mask their hurt, which ignites a conflict. Managing feelings of rejection is difficult because it is so personal, but controlling the impulse to assume that your relational partner is rejecting you and engaging in communication rather than reflexive reaction can help put things in perspective. If your partner doesn’t get excited about the meal you planned and cooked, it could be because they are physically or mentally tired after a long day. The concepts discussed in Chapter 2 can be useful here; for example, perception checking, taking inventory of your attributions, and engaging in information exchange to help determine how each person is punctuating the conflict are useful ways of managing all four of the triggers we’ve discussed.

Serial Arguing

Interpersonal conflict may take the form of serial arguing, which is a repeated pattern of disagreement over an issue. Serial arguments do not necessarily indicate negative or troubled relationships, but any kind of patterned conflict is worth paying attention to. There are three patterns that occur with serial arguing: repeating, mutual hostility, and arguing with assurances (Johnson & Roloff, 2000).

The first pattern of serial arguing is repeating, which means reminding the other person of your complaint—that is, what you want them to start or stop doing. The pattern may continue if the other person repeats their response to your reminder. For example, if Marita reminds Kate that she doesn’t appreciate her sarcastic tone, and Kate responds, “I’m soooo sorry, I forgot how perfect you are,” then the reminder has failed to effect the desired change. A predictable pattern of complaint like this leads participants to view the conflict as irresolvable.

The second pattern of serial arguing is mutual hostility, which occurs when the frustration of repeated conflict leads to negative emotions and increases the likelihood of verbal aggression. Again, a predictable pattern of hostility makes the conflict seem irresolvable and may lead to relationship deterioration.

Whereas the first two patterns of serial arguing entail an increase in pressure on the participants in the conflict, the third pattern offers some relief. If people in an interpersonal conflict offer verbal assurances of their commitment to the relationship, then the problems associated with the other two patterns may be improved. Even though the conflict may not be solved in the interaction, the verbal assurances of commitment imply that there is a willingness to work on solving the conflict in the future, which provides a sense of stability that can benefit the relationship. Although serial arguing is not necessarily bad within a relationship, if the pattern becomes more of a vicious cycle, it can lead to alienation, polarization, and an overall toxic climate, and the problem may seem so irresolvable that people feel trapped and terminate the relationship (Jacobson et al., 2000). There are some negative but common conflict reactions we can monitor and try to avoid, which may also help prevent serial arguing.

Conflict Pitfalls

Two common conflict pitfalls are one-upping and mindreading (Gottman, 1994). One-upping is a quick reaction to communication from another person that escalates the conflict. If Samar comes home late from work and Nicki says, “I wish you would call when you’re going to be late,” and Sam responds, “I wish you would get off my back,” the reaction has escalated the conflict. Mindreading is communication in which one person attributes something to the other using generalizations. If Samar says, “You don’t care whether I come home at all or not!” she is presuming to know Nicki’s thoughts and feelings. Nicki is likely to respond defensively, perhaps saying, “You don’t know how I’m feeling!” One-upping and mindreading are often reactions that are more reflexive than deliberate. Nicki may have received bad news and was eager to get support from Samar when she arrived home. Although Samar perceives Nicki’s comment as criticism and justifies her comments as a reaction to Nicki’s behaviour, Nicki’s comment could actually be a sign of their closeness, in that Nicki appreciates Samar’s emotional support. Samar could have said, “I know, I’m sorry, I was on my cellphone for the past hour with a client who had a lot of problems to work out.” Taking a moment to respond mindfully rather than reacting with a knee-jerk reflex can lead to information exchange, which could deescalate the conflict.

De-escalating Conflict

Validating the person with whom you are in conflict can be an effective way to de-escalate conflict. Although avoiding or retreating may seem like the best option at the moment, one of the key negative traits found in married couples’ conflicts was withdrawal. Often validation can be as simple as demonstrating good listening skills discussed earlier in this book by making eye contact and giving verbal and nonverbal back-channel cues like saying “Mmm-hmm” or nodding your head (Gottman, 1994). This doesn’t mean that you have to give up your own side in a conflict or that you agree with what the other person is saying; rather, you are hearing the other person out, which validates them and may also give you some more information about the conflict that could minimize the likelihood of a reaction rather than a response.

As with all the aspects of communication competence we have discussed so far, you cannot expect that everyone you interact with will have the same knowledge of communication. But it often only takes one person with conflict management skills to make an interaction more effective. Remember that it’s not the quantity of conflict that determines a relationship’s success, it’s how the conflict is managed, and one person’s competent response can de-escalate a conflict. Now we will turn to a discussion of negotiation steps and skills as a more structured way to manage conflict.

Negotiating

We negotiate daily. We may negotiate with an instructor to make up a missed assignment or with our friends to plan activities for the weekend. Negotiation in interpersonal conflict refers to the process of attempting to change or influence conditions within a relationship. The negotiation skills discussed here can be adapted to all types of relational contexts, from romantic partners to co-workers. The stages of negotiating are pre-negotiation, opening, exploration, bargaining, and settlement (Hargie, 2011).

In the pre-negotiation stage, you want to prepare for the encounter. If possible, let the other person know you would like to talk to them and preview the topic, so they will also have the opportunity to prepare. Although it may seem awkward to “set a date” to talk about a conflict, if the other person feels like they were blindsided, their reaction could be negative. Make your preview simple and non-threatening by saying something like, “I’ve noticed that we’ve been arguing a lot about who does what chores around the house. Can we sit down and talk tomorrow when we both get home from class?” Obviously, it won’t always be feasible to set a date if the conflict needs to be handled immediately because the consequences are immediate or if you or the other person has limited availability. In that case, you can still prepare, but make sure you allow time for the other person to digest and respond. During this stage, you also want to figure out your goals for the interaction by reviewing your instrumental, relational, and self-presentation goals. Is getting something done, preserving the relationship, or presenting yourself in a certain way the most important? For example, you may highly rank the instrumental goal of having a clean house, the relational goal of having pleasant interactions with your roommate, or the self-presentation goal of appearing nice and cooperative. Whether your roommate is your best friend from high school or a stranger the school matched you up with could determine the importance of your relational and self-presentation goals. At this point, your goal analysis may lead you away from negotiation—avoiding can be an appropriate and effective conflict management strategy. If you decide to proceed with the negotiation, you will want to determine your ideal outcome and your bottom line or the point at which you decide to break off the negotiation. It’s very important that you realize there is a range between your ideal and your bottom line, and that remaining flexible is key to a successful negotiation—remember that by using collaboration, a new solution could be found that you didn’t think of.

In the opening stage of the negotiation, you want to set the tone for the interaction because the other person will be likely to reciprocate. Generally, it is good to be cooperative and pleasant, which can help open the door for collaboration. You also want to establish common ground by bringing up overlapping interests and using “we” language. It would not be useful to open the negotiation with “You’re such a slob! Didn’t your mom ever teach you how to take care of yourself?” Instead, you might open the negotiation by making small talk about classes that day, then move into the issue at hand. You could set a good tone and establish common ground by saying, “We both put a lot of work into setting up and decorating our space, but now that classes have started, I’ve noticed that we’re really busy and some chores are not getting done.” With some planning and a simple opening like that, you can move into the next stage of negotiation.

There should be a high level of information exchange in the exploration stage. The overarching goal in this stage is to get a panoramic view of the conflict by sharing your perspective and listening to the other person. In this stage, you will likely learn how the other person is punctuating the conflict. Although you may have been mulling over the mess for a few days, your roommate may just now become aware of the conflict. They may also inform you that they usually clean on Sundays but didn’t get to last week because they unexpectedly had to visit their parents. The information that you gather here may clarify the situation enough to end the conflict and cease negotiation. If negotiation continues, the information will be key as you move into the bargaining stage.

The bargaining stage is where you make proposals and concessions. The proposal you make should be informed by what you learned in the exploration stage. Flexibility is important here because you may have to revise your ideal outcome and bottom line based on new information. If your plan was to have a big cleaning day every Thursday, you may now want to propose that your roommate clean on Sunday while you clean on Wednesday. You want to make sure your opening proposal is reasonable and not presented as an ultimatum. “I don’t ever want to see a dish left in the sink” is different from “When dishes are left in the sink too long, they stink and get gross. Can we agree to not leave any dishes in the sink overnight?” Through the proposals you make, you could end up with a win-win situation. If there are areas of disagreement, however, you may have to make concessions or compromise, which can be a partial win or a partial loss. If you hate doing dishes but don’t mind emptying the trash and recycling, you could propose assigning those chores based on preference. If you both hate doing dishes, you could propose that each person be responsible for washing their own dishes right after they use them. If you really hate dishes and have some extra money, you could propose using disposable (and hopefully recyclable) dishes, cups, and utensils.

In the settlement stage, you want to decide on one of the proposals, then summarize the chosen proposal and any related concessions. It is possible that each party can have a different view of the agreed-upon solution. If your roommate thinks you are cleaning the bathroom every other day, and you plan to clean it on Wednesdays, then there could be future conflict. You could summarize and ask for confirmation by saying, “So, it looks like I’ll be in charge of the trash and recycling, and you’ll load and unload the dishwasher. Then I’ll do a general cleaning on Wednesdays, and you’ll do the same on Sundays. Is that right?” Lastly, you’ll need to follow up on the solution to make sure it’s working for both parties. If your roommate goes home again next Sunday and doesn’t get around to cleaning, you may need to go back to the exploration or bargaining stage.

Forgiveness

Individuals tend to experience a wide array of complex emotions following a relational transgression. These emotions are shown to have utility as an initial coping mechanism. For example, fear can result in a protective orientation following a serious transgression, sadness results in contemplation and reflection, and disgust causes us to repel from the source. However, beyond the initial situation, these emotions can be detrimental to one’s mental and physical state. As a result, forgiveness is viewed as a more productive means of dealing with a transgression, along with engaging the one who committed the transgression.

Forgiving is not the act of excusing or condoning. Rather, it is the process whereby negative emotions are transformed into positive emotions for the purpose of bringing emotional normalcy to a relationship. In order to achieve this transformation, the offended party must forgo retribution and claims for retribution.

Dimensions of Forgiveness

The link between reconciliation and forgiveness involves exploring two dimensions of forgiveness: intrapsychic and interpersonal. The intrapsychic dimension relates to the cognitive processes and interpretations associated with a transgression (that is, a person’s internal state), whereas interpersonal forgiveness is the interaction between relational partners. Total forgiveness is defined as including both the intrapsychic and interpersonal components to bring about a return to the conditions prior to the transgression. To only change one’s internal state is silent forgiveness, and only having interpersonal interaction is considered hollow forgiveness.

However, some scholars contend that these two dimensions (intrapsychic and interpersonal) are independent because the complex nature associated with forgiveness involves variations of both dimensions. For example, a partner may not relinquish negative emotions yet choose to remain in the relationship because of other factors (e.g., children or financial concerns). Conversely, a person may grant forgiveness and release all the negative emotions directed towards their partner but exit the relationship because trust cannot be restored. Given this complexity, research has explored whether the transformation of negative emotions to positive emotions eliminates the negative effect associated with a given offence. The conclusions drawn from this research suggest that no correlation exists between forgiveness and unforgiveness. Put simply, although forgiveness may be granted for a given transgression, the negative effect may not be reduced by a corresponding amount.

Predictors of Forgiveness

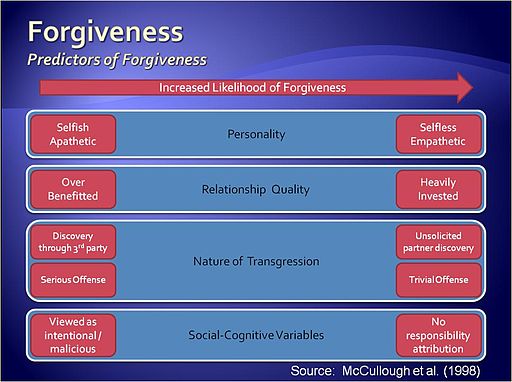

McCullough et al. (1998) outlined the predictors of forgiveness into four broad categories:

- Personality traits of both partners

- Relationship quality

- Nature of the transgression

- Social-cognitive variables

We will discuss these predictors of forgiveness below; they are illustrated in Image 6.7.

Personality Traits of Both Partners

Forgivingness is defined as one’s general tendency to forgive transgressions. However, this tendency differs from forgiveness, which is a response associated with a specific transgression. The characteristics of the forgiving personality as described by Emmons (2000) are as the following:

- Does not seek revenge; effectively regulates the negative effect

- Strong desire for a relationship free of conflict

- Shows empathy towards the offender

- Does not personalize the hurt associated with the transgression

In terms of personality traits, agreeableness and neuroticism (that is, instability, anxiousness, and aggression) show consistency in predicting forgivingness and forgiveness. Because forgiveness requires one to discard any desire for revenge, a vengeful personality tends to not offer forgiveness and may continue to harbour feelings of vengeance long after the transgression occurred.

It has also been shown that agreeableness is inversely correlated with motivations for revenge and avoidance, and positively correlated with benevolence. A person who demonstrates the personality trait of agreeableness is prone to forgiveness and has a general disposition of forgivingness. Conversely, neuroticism was positively correlated with avoidance and vengefulness but negatively correlated with benevolence. Consequently, a neurotic personality is less likely to forgive or to have a disposition of forgivingness.

Although the personality traits of the offended person have a predictive value of forgiveness, the personality of the offender also has an effect on whether forgiveness is offered. Offenders who show sincerity when seeking forgiveness and are persuasive in downplaying the impact of the transgression will have a positive effect on whether the offended party will offer forgiveness. Narcissistic personalities, for example, may be categorized as persuasive transgressors. The narcissist will downplay their transgressions, seeing themselves as perfect and seeking to save face at all costs. Such a dynamic suggests that personality determinants of forgiveness may involve not only the personality of the offended person, but also that of the offender.

Relationship Quality

The quality of a relationship between offended and offending partners can affect whether forgiveness is both sought and given. In essence, the more invested someone is in a relationship, the more prone that person is to minimize the hurt associated with transgressions and seek reconciliation.

McCullough et al. (1998) provides seven reasons for why someone in a relationship will seek to forgive:

-

- Has a high level investment in the relationship (e.g., children, joint finances)

- Views the relationship as a long-term commitment

- Has many common interests with their partner

- Is selfless in regard to their partner

- Is willing to take the viewpoint of their partner (has empathy)

- Assumes that the motives of their partner are in the best interests of the relationship (e.g., criticism is taken as constructive feedback)

- Is willing to apologize for transgressions

Relationship maintenance activities are a critical component to maintaining high-quality relationships. While being heavily invested tends to lead to forgiveness, a person may be in a skewed relationship where the partner who is heavily invested is actually under-benefitted. This leads to one partner being over-benefitted, meaning they are likely to take the relationship for granted and will not be as prone to exhibit relationship repair behaviours. As such, being mindful of the quality of a relationship will best position partners to address transgressions through a stronger willingness to forgive and seek to normalize the relationship.

Another relationship factor that affects forgiveness is the history of past conflict. If past conflicts ended badly (i.e., reconciliation or forgiveness was either not achieved or was only achieved after much conflict), partners will be less willing to seek out or offer forgiveness. Maintaining a balanced relationship in which neither partner is over- or under-benefitted has a positive effect on relationship quality and the tendency to forgive. In that same vein, a partner is are more likely to offer forgiveness if their partner had recently forgiven them for a transgression. However, if a transgression is repeated, resentment begins to build, which has an adverse effect on the offended partner’s desire to offer forgiveness.

Nature of the Transgression

The most notable feature of a transgression to have an effect on forgiveness is the seriousness of the offence. Some transgressions are perceived as being so serious that they are considered unforgivable. To counter the negative effect associated with a severe transgression, the offender may engage in repair strategies to lessen the perceived hurt. The offender’s communication immediately following a transgression has the greatest predictive value on whether forgiveness will be granted.

Consequently, offenders who immediately apologize, take responsibility, and show remorse have the greatest chance of obtaining forgiveness from their partner. Further, self-disclosure of a transgression yields much greater results than if a partner is informed of the transgression through a third party. By taking responsibility for one’s actions and being forthright through self-disclosure of an offence, partners may actually form closer bonds from the reconciliation associated with a serious transgression.

Social-Cognitive Variables

Attributions of responsibility for a given transgression may have an adverse effect on forgiveness. Specifically, if a transgression is viewed as intentional or malicious, the offended partner is less likely to feel empathy and forgive. Based on the notion that forgiveness is driven primarily by empathy, the offender must accept responsibility and seek forgiveness immediately following the transgression because apologies have been shown to elicit empathy from the offended partner. The resulting feelings of empathy in the offended partner may allow them to better relate to the guilt and loneliness their partner may feel as a result of the transgression. In this state of mind, the offended partner is more likely to seek to normalize the relationship through granting forgiveness and restoring closeness with their partner.

Relating Theory to Real Life

- Of the conflict triggers discussed (criticism, demands, cumulative annoyance, and rejection), which one do you find most often triggers a negative reaction from you? What strategies could you use to better manage the trigger and more effectively manage conflict?

- Apply the stages of negotiation to a situation that currently requires negotiation in your life, one from the past, or any imaginary situation.

- Forgiveness can be a complicated process. Consider a situation where either you were forgiven or you forgave someone else. Relate that situation to the theory above with reference to predictors of forgiveness. Were the predictors true?

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been reproduced or adapted from the following resource:

University of Minnesota. (2016). Communication in the real world: An introduction to communication studies. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, except where otherwise noted.

References

Emmons, R. A. (2000). Spirituality and intelligence: Problems and prospects. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 10(1), 57–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327582IJPR1001_6

Gottman, J. M. (1994). What predicts divorce? The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice. Routledge.

Jacobson, N. S., Christensen, A., Prince, S. E., Cordova, J., & Eldridge, K. (2000). Integrative behavioral couple therapy: An acceptance-based, promising new treatment for couple discord. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.2.351

Johnson, K. L., & Roloff, M. E. (2000). Correlates of the perceived resolvability and relational consequences of serial arguing in dating relationships: Argumentative features and the use of coping strategies. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 17(4–5), 676–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407500174011

Maricopa Community College District. (2016). Exploring relationship dynamics. Maricopa Open Digital Press. https://open.maricopa.edu/com110/, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

McCullough, M. E., Rachal, K. C., Sandage, S. J., Worthington, E. L., Jr., Brown, S. W., & Hight, T. L. (1998). Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(6), 1586–1603. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1586

Image Credits (images are listed in order of appearance)

Determinants of Forgiveness Graphic by Interpersonalcomm09, Public domain