2.3 Self-Perception

Just as our perception of others affects how we communicate, so does our perception of ourselves. But what influences our self-perception? How much of our “self” is a product of our own making and how much of it is constructed based on how others react to us? How do we present ourselves to others in ways that maintain our sense of self or challenge how others see us? We will begin to answer these questions in this section as we explore self-concept, self-esteem, and self-presentation.

Self-Concept

Self-concept refers to the overall idea of who a person thinks they are. If I said, “Tell me who you are,” your answers would be clues to how you see yourself—your self-concept. Each person has an overall self-concept that might be a short list of the overarching characteristics they find important. But each person’s self-concept is also influenced by context, meaning that we think differently about ourselves depending on the situation we are in. In some situations, personal characteristics, such as our abilities, personality, and other distinguishing features, will best describe who we are. You might think of yourself as laid back, traditional, funny, open-minded, or driven, or you might label yourself a leader or a thrill-seeker. In other situations, our self-concept may be tied to group or cultural membership. For example, you might consider yourself a member of a book club, a gamer, or a sports geek.

Our self-concept is also formed through our interactions with others and their reactions to us. The concept of the looking-glass self, also known as reflected appraisal, explains that we see ourselves reflected in other people’s reactions to us and then form our self-concept based on how we believe other people see us (Wallace & Tice, 2012). This reflective process of building our self-concept is based on what other people have actually said, such as “You’re a good listener,” and other people’s actions, such as coming to you for advice. These thoughts evoke emotional responses that feed into our self-concept. For example, you may think, “I’m glad that people can count on me to listen to their problems.”

We also develop our self-concept through comparisons to other people. Social comparison theory states that we describe and evaluate ourselves in terms of how we compare to other people. Social comparisons are based on two dimensions: superiority/inferiority and similarity/difference (Hargie, 2021). In terms of superiority and inferiority, we evaluate characteristics such as attractiveness, intelligence, athletic ability, and so on. For example, you may judge yourself to be more intelligent than your brother or less athletic than your best friend, and these judgements are incorporated into your self-concept. This process of comparison and evaluation isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it can have negative consequences if your reference group isn’t appropriate.

Reference groups are the groups we use for social comparison, and they typically change based on what we are evaluating. In terms of athletic ability, many people choose unreasonable reference groups with which to engage in social comparison. If a someone wants to get into better shape and starts an exercise routine, they may be discouraged by difficulty keeping up with the aerobics instructor or their running partner and judge themselves as inferior, which could negatively affect their self-concept. Using as a reference group people who have only recently started a fitness program but have shown progress could help maintain a more accurate and hopefully positive self-concept.

We also engage in social comparison based on similarity and difference. Since self-concept is context specific, similarity may be desirable in some situations and difference more desirable in others. Factors like age and personality may influence whether or not we want to fit in or stand out. Although we compare ourselves to others throughout our lives, adolescence usually brings new pressure to be similar to or different from particular reference groups. Think of all the cliques in high school and how people voluntarily or involuntarily broke off into groups based on popularity, interest, culture, or grade level. Some kids in your high school may have wanted to fit in with and be similar to students in the marching band, as shown in Image 2.5, but be different from the football players. Conversely, athletes were probably more apt to compare themselves, in terms of similar athletic ability, to other athletes rather than to the kids in the band. But social comparison can be complicated by perceptual influences. As we learned earlier, we organize information based on similarity and difference, but these patterns don’t always hold true. Even though students involved in athletics and students involved in arts may seem very different, a dancer or singer may also be very athletic, perhaps even more so than a member of the football team. As with other aspects of perception, there are positive and negative consequences of social comparison.

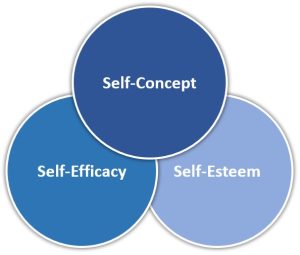

We generally want to know where we fall in terms of ability and performance as compared to others, but what people do with this information and how it affects self-concept varies. Not all people feel they need to be at the top of the list, but some won’t stop until they get the high score on the video game or set a new record in a track-and-field event. Some people strive to be first chair in the clarinet section of the band, while another person may be content to be second chair. We place evaluations on our self-concept based on many factors, and some of these bring in the concepts of self-esteem and self-efficacy, which are components of our self-concept, as can be seen in Image 2.6.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem refers to the judgements and evaluations we make about our self-concept. Although self-concept is a broad description of the self, self-esteem is more specifically an evaluation of the self (Byrne, 1996). If you were again prompted to “Tell me who you are” and then were asked to evaluate (that is, label as good/bad, positive/negative, desirable/undesirable) each of the things you listed about yourself, you would reveal clues about your self-esteem. Like self-concept, self-esteem has both general and specific elements. Generally, some people are more likely to evaluate themselves positively, whereas others are more likely to evaluate themselves negatively (Brockner, 1988). More specifically, our self-esteem varies across our lifespan and across contexts.

How we judge ourselves affects our communication and our behaviours, but not every negative or positive judgement carries the same weight. The negative evaluation of a trait that isn’t very important for our self-concept will likely not result in a loss of self-esteem. For example, you may not be very good at drawing. Although you may appreciate drawing as an art form, you might not consider drawing ability to be a very big part of your self-concept, and if someone criticized your drawing ability, your self-esteem wouldn’t really be affected. On the other hand, you may consider yourself to be good at your job, and you may have spent considerable time and effort developing and improving the skills you need in your work. If your job skills are important to your self-concept and someone critiqued your ability, your self-esteem might definitely be hurt. This doesn’t mean that we can’t be evaluated on something we find important. Even though your job may be very important to your self-concept, you are likely regularly evaluated on it by your superiors and your co-workers. Most of that feedback is likely in the form of constructive criticism, which can still be difficult to receive, but when taken in the spirit of self-improvement, it is valuable and may even enhance your self-concept and self-esteem. In fact, in professional contexts, people with higher self-esteem are more likely to work harder based on negative feedback, are less negatively affected by work stress, are able to handle workplace conflict better, and are better able to work independently and solve problems (Brockner, 1988). Self-esteem isn’t the only factor that contributes to our self-concept; perceptions about our competence also play a role in developing our sense of self.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to the judgements people make about their ability to perform a task in a specific context (Bandura, 1997). Judgements about our self-efficacy influence our self-esteem, which in turn influences our self-concept. The following example also illustrates these interconnections:

Pedro did a good job on his first college speech. During a meeting with his instructor, Pedro indicates that he is confident going into the next speech and thinks he will do well. This skill-based assessment is an indication that Pedro has a high level of self-efficacy related to public speaking. If he does well on the speech, the praise from his classmates and instructor will reinforce his self-efficacy and lead him to positively evaluate his speaking skills, which will contribute to his self-esteem. By the end of the course, Pedro likely thinks of himself as a good public speaker, which may then become an important part of his self-concept.

Throughout these points of connection, it’s important to remember that self-perception affects how we communicate, behave, and perceive other things. Pedro’s increased feeling of self-efficacy may give him more confidence in his delivery, which will likely result in positive feedback that reinforces his self-perception. He may start to perceive his instructor more positively since they share an interest in public speaking, and he may begin to notice other people’s speaking skills more during class presentations and public lectures. Over time, he may even start to think about changing his major to communication or pursuing career options that incorporate public speaking, which would further integrate being “a good public speaker” into his self-concept. You can hopefully see that these interconnections can create powerful positive or negative cycles. Although some of this process is under our control, much of it is also shaped by the people in our lives.

The verbal and nonverbal feedback we get from people affects our feelings of self-efficacy and our self-esteem. As we saw in the example above, being given positive feedback can increase our self-efficacy, which may make us more likely to engage in a similar task in the future (Hargie, 2021). Obviously, negative feedback can lead to decreased self-efficacy and a declining interest in engaging with the activity again. In general, people adjust their expectations about their abilities based on feedback they get from others. Positive feedback tends to make people raise their expectations for themselves, and negative feedback does the opposite, which ultimately affects behaviours and creates the cycle. When feedback from others is different from how we view ourselves, additional cycles may develop that impact self-esteem and self-concept.

Self-Discrepancy Theory

Self-discrepancy theory states that people have beliefs about and expectations for their actual and potential selves that do not always match up with what they experience (Higgins, 1987). To understand this theory, we have to understand the different “selves” that make up our self-concept—the actual, ideal, and ought selves. The actual self consists of the attributes that you or someone else believes you actually possess. The ideal self is made up of the attributes that you or someone else would like you to possess. The ought self consists of the attributes you or someone else believes you should possess.

These different selves can conflict with each other in various combinations. Discrepancies between the actual, ideal, and ought selves can be motivating in some ways and prompt people to act for self-improvement. For example, if your ought self should spend time volunteering for the local animal shelter, then your actual self may be more inclined to do so. Discrepancies between the ideal and ought selves can be especially stressful. For example, many professional women who are also mothers have an ideal view of self that includes professional success and advancement. They may also have an ought self that includes a sense of duty and obligation to be a full-time mother. The actual self may be someone who does fairly well at both but doesn’t quite live up to the expectations of either. These discrepancies do not just create cognitive unease—they also lead to emotional, behavioural, and communicative changes.

The following is a summary of the four potential discrepancies among the selves:

- Actual vs. own ideals: We have an overall feeling that we are not achieving our desires and hopes, which leads to feelings of disappointment, dissatisfaction, and frustration.

- Actual vs. others’ ideals: We have an overall feeling that we are not achieving significant others’ desires and hopes for ourselves, which leads to feelings of shame and embarrassment.

- Actual vs. own ought: We have an overall feeling that we are not meeting our duties and obligations, which can lead to feeling that we have fallen short of our own moral standards.

- Actual vs. others’ ought: We have an overall feeling that we are not meeting what others see as our duties and obligations, which leads to feelings of agitation, including fear of potential punishment.

Influences on Self-Perception

We have already learned that other people influence our self-concept and self-esteem. Although the interactions we have with individuals and groups are definitely important to consider, we must also note the influence that larger, more systemic forces have on our self-perception. Another term often used is our perceived self, which is our subjective appraisal of personal qualities that we ascribe to ourselves (American Psychological Association, 2023). Social and family influences, culture, and the media all play a role in shaping who we think we are and how we feel about ourselves. Although these are powerful socializing forces, there are ways to maintain some control over our self-perception.

Social and Family Influences

Various forces help socialize us into our respective social and cultural groups and play a powerful role in presenting us with options about who we can be. Although we may like to think that our self-perception starts with a blank canvas, our perceptions are limited by our experiences and various social and cultural contexts.

Parents, as shown in Image 2.7, and peers shape our self-perception in both positive and negative ways. Feedback that we get from significant others, which includes close family, can lead to positive or negative views of our self (Hargie, 2021). In the past few years, however, there has been a public discussion and debate about how much positive reinforcement people should give others, especially children. The following questions have been raised: Has our current generation been overpraised? Is the praise given warranted? What are the positive and negative effects of praise? What is the end goal of the praise? Let’s briefly look at this discussion and its connection to self-perception.

Whether or not praise is warranted is very subjective and is specific to each person and context, but in general, questions have been raised about the potential negative effects of too much praise. Motivation is the underlying force that drives us to do things. Sometimes we are intrinsically motivated, meaning that we want to do something for the love of doing it or for the resulting internal satisfaction. At other times, we are extrinsically motivated, meaning that we do something to receive a reward or avoid punishment. If you put effort into completing a short documentary film for a class because you love filmmaking and editing, you have been largely motivated by intrinsic forces. If you complete the documentary because you want an “A” and know that if you fail, your parents will not give you money for your spring break trip, then you are motivated by extrinsic factors. Both can, of course, effectively motivate us. Praise is a form of extrinsic reward, and if there is an actual reward associated with the praise, like money or special recognition, some people speculate that intrinsic motivation will suffer. But what’s so good about intrinsic motivation? Intrinsic motivation is more substantial and long-lasting than extrinsic motivation and can lead to the development of a work ethic and a sense of pride in one’s abilities. Intrinsic motivation can move people to accomplish great things over long periods of time and be happy despite the effort and sacrifices made; extrinsic motivation dies when the reward stops. Additionally, too much praise can lead people to have a misguided sense of their abilities. Instructors who are reluctant to fail students who produce poor-quality work may be setting those students up to be shocked when their supervisor at work criticizes their abilities or output when they are in a professional situation (Hargie, 2021).

Communication patterns develop between parents and children that are common to many verbally and physically abusive relationships. Many children may also receive comparison based motivation from parents that may be discouraging but is not necessary abusive, however, this communication style can result in similar consequences. Such patterns can have negative effects on a child’s self-efficacy and self-esteem. Attributions are links we make to identify the cause of a behaviour. In the case of aggressive, or abusive, parents, they are not able to distinguish between mistakes and intentional behaviours, often seeing honest mistakes as intentional misbehaviours and reacting negatively to the child. Such parents also communicate generally negative evaluations to their child by saying, for example, “You can’t do anything right!” or “You’re a bad child.” When children exhibit positive behaviours, these parents are more likely to use external attributions that diminish the achievement of the child by saying something like, “You only won because the other team was off their game.” In general, this form of parents have unpredictable reactions to their children’s positive and negative behaviour, which creates an uncertain and often scary climate for a child that can lead to lower self-esteem and erratic or aggressive behaviour. The cycles of praise and blame are just two examples of how the family as a socializing force can influence our self-perceptions.

Culture

How people perceive themselves varies across cultures. For example, many cultures exhibit a phenomenon known as the self-enhancement bias, meaning that they tend to emphasize an individual’s desirable qualities relative to other people (Loughnan et al., 2011). But the degree to which people engage in self-enhancement varies. A review of many studies in this area found that people in Western countries such as Canada and the United States were significantly more likely to self-enhance than people in countries such as Japan. Many scholars explain this variation using a common measure of cultural variation that claims people in individualistic cultures are more likely to engage in competition and openly praise accomplishments than people in collectivistic cultures. The difference in self-enhancement has also been tied to economics, with scholars arguing that people in countries with greater income inequality are more likely to view themselves as superior to others or want to be perceived as superior to others (even if they don’t have economic wealth) in order to conform to the country’s values and norms. This holds true because countries with high levels of economic inequality, such as the United States, typically value competition and the right to boast about winning or succeeding, whereas countries with more economic equality, like Japan, have a cultural norm of modesty (Loughnan et al., 2011). The video below discusses individualistic and collectivistic cultures and how complex communication between these different cultures can be.

(Rockson, 2016)

There are some general differences in terms of gender and self-perception that relate to self-concept, self-efficacy, and envisioning ideal selves. As with any cultural differences, these are generalizations that have been supported by research, but they do not represent all individuals within a group. Regarding self-concept, men are more likely to describe themselves in terms of their group membership, and women are more likely to include references to relationships in their self-descriptions. For example, a man may note that he is a fan of the Edmonton Oilers hockey team, an enthusiastic skier, or a member of a philanthropic organization, and a woman may note that she is a mother of two, a marathon runner, or a loyal friend. Socialization and the internalization of societal norms for gender differences accounts for much more of our perceived differences than do innate or natural differences between genders.

Media

The representations we see in the media also affect our self-perception. The vast majority of media images include idealized representations of attractiveness. Despite the fact that the images of people we see in glossy magazines and on movie screens are not typically what we see when we look at the people around us in a classroom, at work, or at the grocery store, many of us continue to hold ourselves to unrealistic standards of beauty and attractiveness. Movies, magazines, and television shows are filled with beautiful people, and less-attractive actors, when they are present in the media, are typically portrayed as the butt of jokes, villains, or only as background extras (Patzer, 2008). Aside from overall attractiveness, the media also offers narrow representations of acceptable body weight or shape.

In terms of self-concept, media representations offer us guidance on what is acceptable or unacceptable and valued or not valued in our society. Media messages, in general, reinforce cultural stereotypes related to race, gender, age, sexual orientation, ability, and class. People from historically marginalized groups must look much harder than those in dominant groups to find positive representations of their identities in media. As a critical thinker, it is important for you to question media messages and to examine who is included and who is excluded.

Advertising, in particular, encourages people to engage in social comparison, regularly communicating to us that we are inferior because we lack a certain product or that we need to change some aspect of our life to keep up with and be similar to others. For example, for many years, advertising targeted at women instilled in them a fear of having a dirty house, selling them products that promised to keep their house clean, make their family happy, and impress their friends and neighbours. Now messages tell us to fear becoming old or unattractive, selling products to keep our skin smooth and clear, which will in turn make us happy and popular.

Self-Presentation

How we perceive ourselves manifests in how we present ourselves to others and how we communicate with others on a daily basis. Self-presentation, also referred to as presenting self, is the process of strategically concealing or revealing personal information to influence others’ perceptions (Human et al., 2012). We engage in this process daily and for different reasons. Although people occasionally intentionally deceive others in the process of self-presentation, in general, we try to make a good impression while still remaining authentic. Since self-presentation helps us meet our instrumental, relational, and identity needs, we stand to lose quite a bit if we are caught intentionally misrepresenting ourselves. As communicators, we sometimes engage in more subtle forms of inauthentic self-presentation. For example, a person may state or imply that they know more about a subject or situation than they actually do in order to seem intelligent or “in the loop.” During a speech, a speaker may rely on a polished and competent delivery to distract from a lack of substantive content. These cases of strategic self-presentation may not ever be found out, but communicators should still avoid them because they do not live up to the standards of ethical communication.

Consciously and competently engaging in self-presentation can have benefits because we can provide others with a more positive and accurate picture of who we are. People who are skilled at impression management are typically more engaging and confident, which allows others to pick up on more cues from which to form impressions (Human et al., 2012). Being a skilled self-presenter draws on many of the practices used by competent communicators, including becoming a higher self-monitor. When self-presentation skills and self-monitoring skills combine, communicators can simultaneously monitor their own expressions, the reactions of others, and the situational and social context (Sosik et al., 2002).

There are two main types of self-presentation: prosocial and self-serving (Sosik et al., 2002). Prosocial self-presentation entails behaviours that present a person as a role model and make the person more likeable and attractive. For example, a supervisor may call on her employees to uphold high standards for business ethics, model that behaviour in her own actions, and compliment others when they exemplify those standards. Self-serving self-presentation entails behaviours that present a person as highly skilled, willing to challenge others, and someone not to be messed with. For example, a supervisor may publicly take credit for the accomplishments of others or publicly critique an employee who failed to meet a particular standard. In summary, prosocial strategies are aimed at benefiting others, whereas self-serving strategies benefit oneself at the expense of others.

In general, we strive to present a public image that matches our self-concept, but we can also use self-presentation strategies to enhance our self-concept (Hargie, 2021). When we present ourselves in order to evoke a positive evaluative response, we are engaging in self-enhancement. In the pursuit of self-enhancement, a person might try to be as appealing as possible in a particular area or with a particular person to gain feedback that will enhance their self-esteem. For example, a singer might train and practise for weeks before singing in front of a well-respected vocal coach but not invest as much effort in preparing to sing in front of friends. Although positive feedback from friends is beneficial, positive feedback from an experienced singer could enhance a person’s self-concept. Self-enhancement can be productive and achieved competently, or it can be used inappropriately. Using self-enhancement behaviours just to gain the approval of others or out of self-centredness may lead people to communicate in ways that are perceived as phony or overbearing and end up making an unfavourable impression (Sosik et al., 2002).

Impression Management

Impression management is a communication strategy that we use to influence how others view us. Basically, it’s the idea that we all have multiple ways that we could show up, and we show up differently depending on the situation.

For example, a doctor who coaches their child’s basketball team, volunteers at a small clinic, and also goes to a weekly book club is not likely to use the same communication strategies in all of these situations. Factors such as language, non-verbal communication, and self-disclosure that we bring to certain situations is all part of our impression management and will vary depending on the situation we find ourselves in.

Characteristics of Impression Management

- We construct different identities: These identities can vary depending on those around us, the situation, and our role at the time.

- Impression management can be deliberate or unconscious: We are not always aware of changes in communication strategies.

- Impression management varies by situation: This variation can be subtle or extreme, depending on the situation.

Watch the video below that discusses impression management and self-monitoring:

(Study Hall, 2023)

Relating Theory to Real Life

- Discuss at least one time when you had a discrepancy or tension between two of the three selves described by self-discrepancy theory (the actual, ideal, and ought selves). What effect did this discrepancy have on your self-concept and/or self-esteem?

- Take one of the socializing forces discussed above (family, culture, or media) and identify at least one positive and one negative influence that it has had on your self-concept and/or self-esteem.

- Discuss some ways that you might strategically engage in self-presentation to influence the impressions of others in an academic, professional, personal, and civic context.

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been reproduced or adapted from the following resource:

University of Minnesota. (2016). Communication in the real world: An introduction to communication studies. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, except where otherwise noted.

References

Adler, R. B., Rolls, J. A., & Proctor II, R. F. (2021). LOOK: Looking out, looking in (4th ed.). Cengage Learning.

American Psychological Association. (2023). APA dictionary of psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/perceived-self

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

Brockner, J. (1988). Self-esteem at work: Research, theory, and practice. D. C. Heath and Co.

Byrne, B. M. (1996). Measuring self-concept across the life span: Issues and instrumentation. American Psychological Association.

Hargie, O. (2021). Skilled interpersonal communication: Research, theory and practice (7th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003182269

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0033-295X.94.3.319

Human, L. J., Biesanz, J. C., Parisotto, K. L., & Dunn, E. W. (2012). Your best self helps reveal your true self: Positive self-presentation leads to more accurate personality impressions. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611407689

Loughnan, S., Kuppens, P., Allik, J., Balazs, K., de Lemus, S., Dumont, K., Gargurevich, R., Hidegkuti, I., Leidner, B., Matos, L., Park, J., Realo, A., Shi, J., Sojo, V. E., Tong, Y.-Y., Vaes, J., Verduyn, P., Yeung, V., & Haslam, N. (2011). Economic inequality is linked to biased self-perception. Psychological Science, 22(10), 1254–1258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417003

Patzer, G. L. (2008). Looks: Why they matter more than you ever imagined. AMACOM.

Rockson, T. (2016, November 22). Understanding collectivism and individualism [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RT-bZ33yB3c

Sosik, J. J., Avolio, B. J., & Jung, D. I. (2002). Beneath the mask: Examining the relationship of self-presentation attributes and impression management to charismatic leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 13(3), 217–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00102-9

Study Hall. (2023, January 18). Impression management and self-monitoring | Intro to human communication | Study Hall [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uDsLm3O-4GI

Wallace, H. M., & Tice, D. M. (2012). Reflected appraisal through a 21st-century looking glass. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 124–140). Guilford Press.

Image Credits (images are listed in order of appearance)

San Jose State University Marching Band Pit Percussionist by Pmlydon, CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 1.3 self-concept, self-efficacy, self-esteem by Stevy.Scarbrough, CC BY-SA 4.0