5.4 Emotions and Relationships

Have you ever been at a movie and let out a bellowing laugh and snort only to realize no one else is laughing? Have you ever become uncomfortable when someone cries in class or in a public place? Emotions are clearly personal because they often project what we’re feeling on the inside to those around us whether we want it to show or not (University of Minnesota, 2016). Emotions are also interpersonal in that another person’s show of emotion usually triggers a reaction from us—perhaps support if the person is a close friend or awkwardness if the person is a stranger. Emotions are central to any interpersonal relationship, and it’s important to know what causes and influences emotions so we can better understand our own emotions and better respond to others when they display emotions (University of Minnesota, 2016).

Emotions are physiological, behavioural, and communicative reactions to stimuli that are cognitively processed and experienced as emotional (Planalp et al., 2006). This definition includes several important dimensions of emotions. First, emotions are often internally experienced through physiological changes such as increased heart rate, a tense stomach, or a cold chill (University of Minnesota, 2016). These physiological reactions may not be noticeable to others and are therefore intrapersonal unless we exhibit some change in behaviour that clues others into our internal state or we verbally or nonverbally communicate our internal state (University of Minnesota, 2016). Sometimes our behaviour is voluntary—we ignore someone, which may indicate we are angry with them—or involuntary—we fidget or avoid eye contact while talking because we are nervous. When we communicate our emotions, we call attention to ourselves and express information to others that may inform how they should react. For example, when someone we care about displays behaviours associated with sadness, we are likely to know that they need support (Planalp et al., 2006). We learn, through socialization, how to read and display emotions, though some people are undoubtedly better at reading emotions than others. However, as with most aspects of communication, we can all learn to become more competent with increased knowledge and effort (University of Minnesota, 2016).

Primary emotions are innate emotions that are experienced for short periods of time and appear rapidly, usually as a reaction to an outside stimulus, and are experienced similarly across cultures (University of Minnesota, 2016). The primary emotions are joy, distress, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust. Members of a remote tribe in New Guinea, who had never been exposed to Westerners, were able to identify these basic emotions when shown photographs of Americans making corresponding facial expressions (Evans, 2001).

Secondary emotions are not as innate as primary emotions, and they do not have a corresponding facial expression that makes them universally recognizable (University of Minnesota, 2016). These emotions are processed by a different part of the brain that requires higher-order thinking, so they are not reflexive. Secondary emotions are love, guilt, shame, embarrassment, pride, envy, and jealousy (Evans, 2001). These emotions develop over time, take longer to fade away, and are interpersonal because they are most often experienced in relation to real or imagined others. You can be fearful of a the dark but feel guilty about an unkind comment made to your mother or embarrassed at the thought of doing poorly on a presentation in front of an audience (University of Minnesota, 2016). Because these emotions require more processing, they are more easily influenced by thoughts and can be managed, which means we can become more competent communicators by becoming more aware of how we experience and express secondary emotions (University of Minnesota, 2016). Although there is more cultural variation in the meaning and expression of secondary emotions, they are still universal in that they are experienced by all cultures. It’s hard to imagine what our lives would be like without emotions, and, in fact, many scientists believe we wouldn’t be here without them. These emotions are not always felt in isolation, meaning that they often present together and can be conflicting. For example, you can be both joyful and sad at the same time, something that is often referred to as having mixed emotions (University of Minnesota, 2016).

Understanding Emotions

To start our examination of the idea of emotions and feelings and how they relate to harmony and discord in a relationship, it is important to differentiate between emotions and feelings. Emotions are our physical reactions to stimuli in the outside environment. They can be objectively measured by blood flow, brain activity, and nonverbal reactions to things because they are activated through neurotransmitters and hormones released by the brain. Feelings are the conscious experience of emotional reactions. They are our responses to thoughts and interpretations given to emotions based on experiences, memory, expectations, and personality. So, there is a relationship between emotions and feelings, but the two things are different.

Being emotional is an inherent part of being human. However, the way we communicate about emotion can make emotion seem negative. Have you ever said, “Don’t feel that way” or “I shouldn’t feel this way”? When we negate our own or someone else’s emotions, we are negating ourselves or that person and dismissing the right to have emotional responses (University of Minnesota, 2016). At the same time, though, no one else can make you “feel” a specific way—our emotions are our emotions. They are how we interpret and cope with life. A person may set up a context where you experience an emotion, but you are the one who is still experiencing that emotion and allowing yourself to experience that emotion. If you don’t like “feeling” a specific way, then you can change it. We all have the ability to alter our emotions. Altering our emotional states (in a proactive way) is how we get through life (University of Minnesota, 2016). Maybe you just broke up with a romantic partner and listening to music helps you work through the grief you are experiencing. Someone else may need to openly communicate about how they are feeling in an effort to work through their emotions. Everyone has a different way of processing their emotions (University of Minnesota, 2016).

Attempting to deny that an emotion exists is not an effective way to process emotions (University of Minnesota, 2016). Think of this like a balloon. With each breath of air, you blow into the balloon. Eventually, the balloon will get to a point where it cannot handle any more air, and it explodes. Humans can be the same way with emotions when we bottle them up inside. The final breath of air in our emotional balloon doesn’t have to be big or intense, but it can still cause tremendous emotional outpouring that is often very damaging to the person and their interpersonal relationships (University of Minnesota, 2016). Research has demonstrated that handling negative emotions during conflicts within a marriage can lead to faster de-escalations of conflicts and faster conflict mediation between spouses (Levenson et al., 2014).

Functions of Emotions

Intrapersonal Functions of Emotions

Emotions are rapid information-processing systems that help us act with minimal thinking (Tooby & Cosmides, 2008). Problems associated with birth, battle, and death have occurred throughout history, and emotions evolved to aid humans in adapting to those situations rapidly and with minimal conscious cognitive effort. If we did not have emotions, we could not make rapid decisions about whether to attack, defend, flee, care for others, reject food, or approach something useful, all of which have been functionally adaptive in human history and helped us to survive. For instance, drinking spoiled milk or eating rotten eggs has negative consequences for our welfare. The emotion of disgust, however, helps us immediately take action by not ingesting bad food in the first place or by vomiting it out. This response is adaptive because it ultimately aids in our survival and allows us to act immediately without much thinking. In some instances, taking the time to sit and rationally think about what to do—calculating cost-benefit ratios in one’s mind—is a luxury that might cost one’s life. Emotions evolved so that we can act without that depth of thought.

Emotions Prepare the Body for Immediate Action

Emotions prepare us for behaviour. When triggered, emotions orchestrate systems such as perception, attention, inference, learning, memory, goal choice, motivational priorities, physiological reactions, motor behaviours, and behavioural decision making (Tooby & Cosmides, 2008). Emotions simultaneously activate certain systems and deactivate others in order to prevent the chaos of competing systems operating at the same time, allowing for coordinated responses to environmental stimuli (Levenson, 1999). For instance, when we are afraid, our bodies shut down temporarily unneeded digestive processes, resulting in saliva reduction (a dry mouth), blood flows disproportionately to the lower half of the body, the visual field expands, and air is breathed in, all preparing the body to flee. Emotions initiate a system of components that includes subjective experience, expressive behaviours, physiological reactions, action tendencies, and cognition, all for the purpose of specific actions—the term “emotion” is, in reality, a metaphor for these reactions.

One common misunderstanding when thinking about emotions is the belief that emotions must always directly produce action. This is not true. Emotion certainly prepares the body for action, but whether someone actually engages in action is dependent on many factors, such as the context within which the emotion has occurred, the target of the emotion, the perceived consequences of one’s actions, previous experiences, and so on (Baumeister et al., 2007; Matsumoto & Wilson, 2008). Thus, emotions are just one of many determinants of behaviour, although an important one.

Emotions Influence Thoughts

Emotions are also connected to thoughts and memories. Memories are not just facts that are encoded in our brains; they are coloured with the emotions felt at the times the memories occurred (Wang & Ross, 2007). Thus, emotions serve as the neural glue that connects those disparate facts in our minds. That is why it is easier to remember happy thoughts when happy, and angry times when angry. Emotions serve as the basis of many attitudes, values, and beliefs that we have about the world and the people around us. Without emotions, those attitudes, values, and beliefs would just be statements without meaning—emotions give those statements meaning. Emotions influence our thinking processes, sometimes in constructive ways, but sometimes not. It is difficult to think critically and clearly when we feel intense emotions and easier when we are not overwhelmed with emotions (Matsumoto et al., 2006).

Emotions Motivate Future Behaviours

Because emotions prepare our bodies for immediate action, influence thoughts, and can be felt, they are important motivators of future behaviour. Many of us strive to experience feelings of satisfaction, joy, pride, or triumph in our accomplishments and achievements. At the same time, we also work very hard to avoid strong “negative” feelings; for example, once we have felt the emotion of disgust when drinking spoiled milk, we generally work very hard to avoid having those feelings again. For example, we might check the expiration date on the label before buying the milk, smell the milk before drinking it, or watch to see if the milk curdles in a cup of coffee before drinking it. Emotions, therefore, not only influence immediate actions, but also serve as an important motivational basis for future behaviours.

Interpersonal Functions of Emotions

Emotions are expressed both verbally through words and nonverbally through facial expressions, voices, gestures, body postures, and movements. We constantly express emotions when interacting with others, and others can reliably judge those emotional expressions (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002; Matsumoto, 2001). Thus, emotions have signal value to others and influence others and our social interactions. Emotional expressions communicate information to others about our feelings, intentions, relationship with the target of the emotions, and the environment.

Emotional Expressions Facilitate Specific Behaviours in Perceivers

Because facial expressions of emotion are universal social signals, they contain meaning not only about the psychological state but also about that person’s intent and subsequent behaviour. This information affects what the perceiver is likely to do. People observing fearful faces, for instance, are more likely to produce approach-related behaviours, whereas people who observe angry faces are more likely to produce avoidance-related behaviours (Marsh et al., 2005). Even the subliminal presentation of smiles produces increases in how much beverage people pour and consume and how much they are willing to pay for it; the presentation of angry faces decreases these behaviours (Winkielman et al., 2005). Also, emotional displays evoke specific, complementary emotional responses from observers; for example, anger evokes fear in others (Dimberg & Ohman, 1996; Esteves et al., 1994), whereas distress evokes sympathy and aid (Eisenberg et al., 1989).

Expressing Emotions

Emotion sharing involves communicating the circumstances, thoughts, and feelings surrounding an emotional event; it usually starts immediately following an emotional episode (University of Minnesota, 2016). The intensity of the emotional event corresponds with the frequency and length of the sharing, with high-intensity events being told more often and over a longer period of time (University of Minnesota, 2016). Research shows that people communicate with others after almost any emotional event, positive or negative, and that emotion sharing offers intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits because individuals feel inner satisfaction and relief after sharing, and social bonds are strengthened through the interaction (Rimé, 2007).

Our social bonds are enhanced through emotion sharing because the support we receive from our relational partners increases our sense of closeness and interdependence (University of Minnesota, 2016). We should also be aware that our expressions of emotion are infectious owing to emotional contagion, or the spreading of emotion from one person to another (Hargie, 2011). Think about a time when someone around you got the giggles and you couldn’t help but laugh along with them, even if you didn’t know what was funny. While those experiences can be uplifting, the other side of emotional contagion can be unpleasant. We’ve probably all worked with someone or had a family member who couldn’t seem to say anything positive, and others react by becoming increasingly frustrated with them (University of Minnesota, 2016).

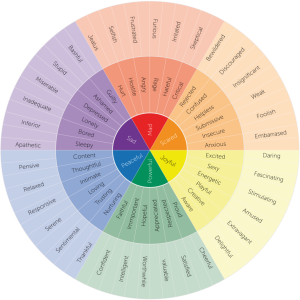

To verbally express our emotions, it is important that we develop an emotional vocabulary (University of Minnesota, 2016). The more specific we can be when verbally communicating our emotions, the less ambiguous they will be for the person decoding our message. As we expand our emotional vocabulary, we are able to convey the intensity of the emotion we’re feeling, whether it is mild, moderate, or intense. For example, happy is mild, delighted is moderate, and ecstatic is intense; ignored is mild, rejected is moderate, and abandoned is intense (Hargie, 2011). Aside from conveying the intensity of your emotions, you can also verbally frame your emotions in a way that allows you to have more control over them (University of Minnesota, 2016).

It’s important to distinguish among our emotional states and how we interpret an emotional state. For example, you can feel sad or depressed because those are feelings. However, you cannot feel alienated because this is not a feeling. Your sadness and depression may lead you to perceive yourself as alienated, but alienation is a perception (that is, a thought rather than an emotion) of one’s self and not an actual emotional state. There are several evaluative terms that people ascribe to themselves, usually in the process of blaming others for their feelings, that they label as emotions, but which are in actuality evaluations and not emotions. Examples of these include words such as abandoned, pressured, unappreciated, unwanted, intimidated, and unwanted. Instead, using actual emotional words will communicate your feelings effectively. Most of us have a very limited emotional vocabulary. Think about it—how many emotion words can you even list? And more importantly, how many emotional experiences can you appropriately label? One of the best ways to improve your ability to be assertive is to improve your emotional vocabulary. A great tool for this is a Feelings Wheel as shown in Image 5.5 below.

As you can see, there are a lot of words that can be used to describe our emotions. One of the world’s leading experts in emotions is Susan David, and her research shows that we need to have an emotional vocabulary of at least 30 words in order to accurately experience, express, and ultimately work through our emotions. The video below is a TedTalk by Susan David in which she discusses the importance of expressing, and not denying, our emotions.

(TED, 2018)

The points below give examples of effective ways in which to share your emotions, including describing the emotions, the behaviour that triggered the emotions, and the “why” behind them.

- The emotion(s): Explicitly state the emotion(s) you are experiencing. The more specific you can be, the more likely the other person will be to understand what you are feeling. Here, it is important to have a rich and nuanced emotional vocabulary to better understand and express these emotions to others because emotions can be mild, moderate, or intense. For example, consider the difference between the terms sad, melancholy, and despondent. Use the Feelings Wheel above (Image 5.5) to identify feelings.

- The behaviour: Just as it is important to be able to describe a specific emotion, it is likewise important to describe the specific behaviour(s) that triggered the emotion. For example, if your roommate leaves dirty dishes on the kitchen counter, you may feel annoyed. When describing the behaviour, you should state only what you have observed, objectively and specifically, and not in an evaluative or accusatory manner. “Leaving dirty dishes in the kitchen” is an appropriate way to describe behaviour, whereas “acting like a jerk” is an evaluation of that behaviour and is not very conducive to a productive interaction. Instead, you could say, “I feel annoyed when dirty dishes are left in the kitchen,” versus “I feel annoyed when you act like a jerk.” The latter statement also contains a “you” statement rather than an “I” statement.

- The “why”: Finally, it’s useful to include a “why” in your “I” statement. Consider expressing a reason for why the behaviour bothers you and leads to your particular emotional reaction. The why offers an explanation, interpretation, effect, or consequence of the behaviour. One example might be “I feel annoyed when dirty dishes are left around the kitchen because it attracts cockroaches.” When describing the why, avoid “you” language. For example, saying “I feel sad when our plans are broken because you are neglecting me” still inserts that problematic “you,” which suggests blame and could lead to the other person becoming defensive. Instead, consider something like “I feel sad when our plans are broken because I want to spend more time together.”

“You” can easily creep into all three parts of an “I” message and can be tricky to avoid at first, so you may want to mentally rehearse or even write down what you plan to say. Also, it is a good idea to repeat the statement back to yourself and think about how you might respond if someone said the exact same thing to you in a similar situation. If it would cause you to react negatively or defensively, revise your statement.

You might find that, in some situations, avoiding “you” may not be productive. At times, it might be useful to share the thoughts you attach to another person’s behaviour. You can share your perspective by using a phrase such as “I took it to mean ….” In this case, “you” might show up in your interpretation. However, you can reduce the potential for defensiveness by using language that reflects tentativeness and ownership. An example of this is “I’m confused about the dishes being left because it seems out of the norm for you, and I’m wondering if something is going on.” Another example might be “I get frustrated when the dishes are left on the counter because I remember talking about this before, and I think I’m not being heard.” We will learn more about language and actions that contribute to and reduce defensiveness in future chapters. Understanding and asserting our emotions is important and challenging work.

In a time when so much of our communication is electronically mediated, it is likely that we will communicate emotions through the written word in an email, text, or instant message (University of Minnesota, 2016). We may also still resort to pen and paper when sending someone a thank-you note, a birthday card, or a sympathy card. Communicating emotions through the written (or typed) word can have advantages such as time to compose your thoughts and convey the details of what you’re feeling (University of Minnesota, 2016). There are also disadvantages in that important context and nonverbal communication can’t be included. Elements such as facial expressions and tone of voice offer much insight into emotions that may not be expressed verbally (University of Minnesota, 2016). Immediate feedback is also lacking from written communication. Sometimes people respond immediately to a text or email, but think about how frustrating it is when you text someone and they don’t get back to you right away. If you’re in need of emotional support or want validation for an emotional message you just sent, waiting for a response could end up negatively affecting your emotional state and your relationship (University of Minnesota, 2016).

Debilitative Emotions

Debilitative emotions are harmful and difficult emotions that detract from effective functioning. This is the opposite of facilitative emotions, which are emotions that would contribute to our effective functioning. The level, or intensity, of the emotion we are feeling, determines our response to the emotion. There is a difference between “a little upset” and “irate.” Debilitative emotions can affect our ability to interpret emotions, and most involve communication that has led to conflict. Some intensity in emotion can be constructive, but too much intensity makes the situation worse. The other part of debilitative emotions is their duration. Again, there is a difference between “momentarily” feeling a certain way and “forever” feeling a certain way. When something happens, sometimes you feel like your whole life has crashed down on you and that there’s no way to pick up the pieces. One unexpected, disappointing situation does not have to completely change the core of your being. This can result in rumination, which is repeatedly thinking about or dwelling on negative thoughts and emotions. If something bad does happen, a strategy for working through these emotions is to give yourself a few days to think it over. It’s still important to recognize your feelings, as well as understand them, instead of completely brushing them off. After those few days are over, you may realize that there’s much more out there and remind yourself about what makes you happy and the goals you want to accomplish. Some debilitative emotions take a long time to recover from, but allowing yourself to let go of grudges so that they don’t affect your future communication and interpersonal relationships is important for emotional health.

Most emotions are the result of our way of thinking. Debilitative emotions arise from accepting a number of irrational thoughts that are called fallacies. These fallacies lead to illogical and false conclusions that in turn become debilitative emotions. We may not be aware of these thoughts, which makes them very powerful.

Here are some fallacies that lead to the arousal of debilitative emotions:

- Fallacy of Perfection: This fallacy is thinking we should be able to handle every situation perfectly with no room for error. We constantly strive for an unrealistic goal of perfection. We may think that others will not appreciate us if we are not “perfect,” which makes it difficult for us to admit our mistakes. Although it’s tempting to try to appear perfect, the costs of such deception are very high. If others ever find you out, they’ll see you as being phony. This illusion of perfection will lower your self-confidence because nothing and no one is perfect and may hinder others from liking you. Like everyone else, you make mistakes from time to time, and there is no reason to hide this.

- Fallacy of Helplessness: This fallacy is being convinced that powers beyond a person’s control can determine their satisfaction or happiness. For example, when people say “I don’t know how” or “I can’t do anything about it,” they are expressing helplessness or an unwillingness to change—the “can’ts” are really justifications for not wanting to change. For instance, lonely people tend to attribute their poor interpersonal relationships to uncontrollable causes. This irrational thinking increases debilitative emotions and empowers them.

- Fallacy of Catastrophic Expectations: The fallacy is people working on the assumption that if something bad can possibly happen, it will; that is, they imagine the worst possible catastrophic consequences. For example, someone may think “If I speak about this issue, everyone will laugh at me.” This in turn creates harmful debilitative emotions and a self-fulfilling prophecy will begin to build. For instance, a study revealed that people who believed that their romantic partners would not change for the better were likely to behave in ways that contributed to the breakup of the relationship.

- Fallacy of Overgeneralization: This fallacy comprises two types. The first type of overgeneralization occurs when a belief is based on a limited amount of evidence. For instance, saying, “I’m so stupid, I can’t even figure out how to download music onto my smartphone.” The second type overgeneralization takes place when we exaggerate shortcomings. For example, when we say, “You never listen to me” or “You are always late.” These statements are inevitably false (events seldom “always” or “never” occur), and saying things like this lead to nothing other than anger and debilitative emotions.

Culture and Emotions

Although our shared past dictates some universal similarities in emotions, triggers for emotions and the norms for displaying emotions vary widely. Certain emotional scripts that we follow are socially, culturally, and historically situated (University of Minnesota, 2016). Take the example of falling in love. Westerners may be tempted to critique the practice of arranged marriages in other cultures and question a relationship that isn’t based on falling in love. However, arranged marriages have historically been a part of Western culture, and the emotional narrative of falling in love has only recently become a part of that culture. Even though we know that compatible values and shared social networks rather than passion are more likely to predict the success of a long-term romantic relationship, Western norms privilege the emotional role of falling in love in our courtship narratives and practices (Crozier, 2006). While this example shows how emotions tie into larger social and cultural narratives, rules and norms for displaying emotions affect our day-to-day interactions (University of Minnesota, 2016).

Display rules are sociocultural norms that influence emotional expression (University of Minnesota, 2016). These rules influence who can express emotions, which emotions can be expressed, and how intense the expressions can be. In individualistic cultures, where personal experience and self-determination are values built into cultural practices and communication, expressing emotions is viewed as a personal right. In fact, the outward expression of our inner states may be exaggerated because getting attention from those around us is accepted and even expected in individualistic cultures such as those in Canada and the United States (Safdar et al., 2009). In collectivistic cultures, emotions are viewed as more interactional and less individual, which ties them into social context rather than into an individual right to free expression. An expression of emotion reflects on the family and cultural group rather than only on the individual (University of Minnesota, 2016), so emotional displays are more controlled. Maintaining group harmony and relationships is a primary cultural value, which is very different from the more individualistic notion of having the right to get something off your chest (University of Minnesota, 2016).

There are also cultural norms regarding which types of emotions can be expressed (University of Minnesota, 2016). In individualistic cultures, especially in the Canada and United States, there is a cultural expectation that people will exhibit positive emotions (University of Minnesota, 2016). People seek out happy situations and communicate positive emotions even when they do not necessarily feel them. Being positive implicitly communicates that you have achieved your personal goals, have a comfortable life, and have a healthy inner self (Mesquita & Albert, 2007). In these individualistic cultures, failure to express positive emotions could lead others to view you as a failure or to recommend psychological help or therapy. The cultural predisposition to express positive emotions is not universal. The people who live on the island of Ifalik in the Pacific do not encourage the expression of happiness because they believe it will lead people to neglect their duties (Mesquita & Albert, 2007). Similarly, collectivistic cultures may view expressions of positive emotions negatively because someone is bringing undue attention to themselves, which could upset group harmony and potentially elicit jealous reactions from others (University of Minnesota, 2016).

Emotional expressions of grief also vary among cultures and are often tied to religious or social expectations (Lobar et al., 2006). Thai and Filipino funeral services often include wailing, a more intense and loud form of crying, which shows respect for the deceased (University of Minnesota, 2016). The intensity of the wailing varies based on the importance of the individual who died and the closeness of the relationship between the mourner and the deceased. Therefore, close relatives like spouses, children, or parents would be expected to wail louder than distant relatives or friends (University of Minnesota, 2016).

This section has provided an overview of many aspects of emotions and how they tie into our relationships. Another related and important concept in reference to emotions is our emotional intelligence (EQ), which will be discussed on the next page.

Relating Theory to Real Life

- In what situations would you be more likely to communicate emotions through electronic means rather than in person? Why?

- Can you think of a display rule for emotions that is not mentioned in the chapter? What is it and why do you think this norm developed?

- When you are trying to determine someone’s emotional state, what nonverbal communication do you look for and why?

- Which of the fallacies that often lead to debilitative emotions do you more commonly experience? Provide an example of when that happened.

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been copied and adapted from the following resource:

Maricopa Community College District. (2016). Exploring relationship dynamics. Maricopa Open Digital Press. https://open.maricopa.edu/com110/, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, except where otherwise noted.

References

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., DeWall, C. N., & Zhang, L. (2007). How emotion shapes behavior: Feedback, anticipation, and reflection, rather than direct causation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 167–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868307301033

Crozier, W. R. (2006). Blushing and the social emotions: The self unmasked. Palgrave Macmillan.

Dimberg, U., & Ohman, A. (1996). Behold the wrath: Psychophysiological responses to facial stimuli. Motivation and Emotion, 20(2), 149–182. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/BF02253869

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Miller, P. A., Fultz, J., Shell, R., Mathy, R. M., & Reno, R. R. (1989). Relation of sympathy and distress to prosocial behavior: A multimethod study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(1), 55–66. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.57.1.55

Elfenbein, H. A., & Ambady, N. (2002). On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 205–235. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.203

Esteves, F., Dimberg, U., & Ohman, A. (1994). Automatically elicited fear: Conditioned skin conductance responses to masked facial expressions. Cognition and Emotion, 8(5), 393–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939408408949

Evans, D. (2001). Emotion: The science of sentiment. Oxford University Press.

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice. Routledge.

Levenson, R. W. (1999). The intrapersonal functions of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 13(5), 481–504. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/026999399379159

Levenson, R. W., Haase, C. M., Bloch, L., Holley, S. R., & Seider, B. H. (2014). Emotion regulation in couples. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 267–283). The Guilford Press.

Lobar, S. L., Youngblut, J. M., & Brooten, D. (2006). Cross-cultural beliefs, ceremonies, and rituals surrounding death of a loved one. Pediatric Nursing, 32(1), 44–50.

Marsh, A. A., Ambady, N., & Kleck, R. E. (2005). The effects of fear and anger facial expressions on approach- and avoidance-related behaviors. Emotion, 5(1), 119–124. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.119

Matsumoto, D. (2001). Culture and emotion. In D. Matsumoto (Ed.), The handbook of culture and psychology (pp. 171–194). Oxford University Press.

Matsumoto, D., Hirayama, S., & LeRoux, J. A. (2006). Psychological skills related to intercultural adjustment. In P. T. P. Wong & L. C. J. Wong (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 387–405). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-26238-5_16

Matsumoto, D., & Wilson, J. (2008). Culture, emotion, and motivation. In R. M. Sorrentino & S. Yamaguchi (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition across cultures (pp. 541–563). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-373694-9.00023-4

Mesquita, B., & Albert, D. (2007). The cultural regulation of emotions. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 267–283). The Guilford Press.

Planalp, S., Fitness, J., & Fehr, B. (2006). Emotion in theories of close relationships. In A. L. Vangelisti and D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. Cambridge University Press.

Rimé, B. (2007). Interpersonal emotion regulation. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 466–485). The Guilford Press.

Safdar, S., Friedlmeier, W., Matsumoto, D., Hee Yoo, S., Kwantes, C. T., & Kakai, H. (2009). Variations of emotional display rules within and across cultures: A comparison between Canada, USA, and Japan. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 41(1), 1–10. http://davidmatsumoto.com/content/2009SafdaretalCanadianJBehaviouralScience.pdf

TED. (2018, February 20). The gift and power of emotional courage | Susan David [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NDQ1Mi5I4rg

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2008). The evolutionary psychology of the emotions and their relationship to internal regulatory variables. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 114–137). The Guilford Press.

University of Minnesota. (2016). Communication in the real world: An introduction to communication studies. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Wang, Q., & Ross, M. (2007). Culture and memory. In S. Kitayama & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of cultural psychology (pp. 645–667). The Guilford Press.

Winkielman, P., Berridge, K. C., & Wilbarger, J. L. (2005). Unconscious affective reactions to masked happy versus angry faces influence consumption behavior and judgments of value. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(1), 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271309

Image Credits (images are listed in order of appearance)

Emotion collage by Jtneill, CC BY-SA 4.0

Young Woman Thinking by Petr Kratochvil, Public domain

The Feeling Wheel by Feeling Wheel, CC BY-SA 4.0