13 Chapter 9 – Pierre Auguste Renoir & Edgar Degas

Megan Bylsma

Audio recording of chapter opening segment:

Audio recording of the full chapter can be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1U2bEjx-pvp7Hp__MDGvh-Fm57qiIUQcd/view?usp=sharing

There are two kinds of Impressionism – Landscape Impressionism and Urban Impressionism. Landscape Impressionism is easily showcased in the work of Claude Monet, with is regular and careful studies of light in nature. The Urban Impressionists were interested in similar things as Monet, but they were more closely tied to the ideals put forward by Baudelaire – the idea that modern day heroes exist and deserve examination. The combination of the idea of the value of daily life and the Realist approach to depicting light, the Urban Impressionists captured the life of the city and two major proponents of this approach were Pierre Auguste Renoir and Edgar Degas.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

While Edgar Degas embraced the depiction of urban life to the forsaking of all other depictions of existence (he hated working in natural light and was one of the very few Impressionists who preferred painting indoors under electric or gas light) Pierre Auguste Renoir was not so interested in the impacts of artificial light on subjects as he was on depicting humans. He was first a landscape painter but when a friendship with a wealthy landowner ended Renoir’s access to landscapes he wanted to paint also ended, so he moved his focus to subjects closer at hand – people.

Renoir’s paintings feature human interaction and human existence through the eyes of an Impressionist who valued light and colour. He straddled the landscape genre and the figurative tradition and in his work the impact of the landscape practices of Impressionism on urban human subjects is clearly seen.

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “How to recognize Renoir: The Swing,” in Smarthistory, April 8, 2018, https://smarthistory.org/renoir-swing/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

When artists like Pierre-Auguste Renoir painted portraits of real people, their work became embedded with clues about cultural beliefs at a particular moment in time — including notions of beauty, propriety, status, and gender. In this portrait by Renoir, the artist captured the likeness of Madame Charpentier with her two children in an intimate setting within the family’s elegant Parisian townhouse.

This work is one of several commissioned by Georges Charpentier, an influential publisher and an early collector of Renoir’s work. In this portrait, Renoir depicts Marguérite Charpentier seated on a richly patterned settee alongside her two children and the family’s large Newfoundland dog in a small room filled with precious objects including Japanese screens, crystal and porcelain. Renoir’s palette is lush and his brushwork confident; the careful composition with its strong diagonals invites the viewer into this private space.

This large-scale work received favorable reviews when it was exhibited in a prominent position at the Salon of 1879 in Paris, and Renoir later acknowledged the efforts of Madame Charpentier in helping him gain subsequent portrait commissions. However, in the decades after its initial reception, viewers have often been surprised to learn that one of the children is a boy, since both children are dressed alike. This essay analyzes the garments and accessories worn by Madame Charpentier and her children as markers of status and gender at that time in history. Gender —the cultural construction of identity that distinguishes man from woman and boy from girl —is typically represented through the fashioning of the body, including the clothing and accessories, the styling of the hair and the wearing of makeup or other body modifications.

In this portrait, Madame Charpentier is dressed in a long-sleeved black silk afternoon dress expansively trimmed with lace. Each element of her dress is indicative of her stature as the wife of a wealthy man.

Her close-fitting dress is floor length, with a train that pools on the floor beside her to reveal her white ruffled underskirt. The dress has no bustle, but rather is flat-backed; this style of dress was in fashion for a brief interval of two or three years towards the end of this decade, and this small detail marks the wearer as a close follower of fashion.

Marguerite has added several pieces of jewelry to her ensemble to signal the family’s wealth, including pearl earrings, a daisy brooch pinned to her left shoulder, two heavy gold bangles on both wrists, and several rings on her fingers.

The color of the dress signals chic, rather than mourning; black was a fashionable color for an elegant afternoon dress that would be worn to receive visitors or go visiting in one’s social circle. Madame Charpentier was known for her sophisticated literary salons in which she entertained writers like Flaubert and Zola, and this formal daywear dress would be suitable for just such a gathering.

In Renoir’s portrait, the children — Georgette, age six, and Paul, age three — are dressed in identical sleeveless, open-neckline, dropped-waist short dresses made of pale blue moiré silk trimmed with white silk. Both children have similar hairstyles with shoulder-length wavy hair. The only discernible difference in their attire is their footwear; Georgette wears shoes with a small heel, while Paul wears flat shoes with a mid-foot strap. These children, dressed alike in their expensive and elegantly trimmed silk frocks, are fashionable accessories for their elegant mother.

Audio recording continued:

The identical dresses worn by the Charpentier children in this painting reveal a little-known aspect of nineteenth-century western dress codes in which infants and young children were dressed alike in dresses or petticoats until about age four or five. At this time in history, when doing laundry was a tedious and lengthy process, having young children wear petticoats or frocks until they were toilet-trained made sense from a practical standpoint. As well, infants and young children were seen as asexual beings and for this reason were dressed alike. For example, in the fashion plate shown here, the child is dressed in a jacket and skirt that could be worn by either boy or girl.

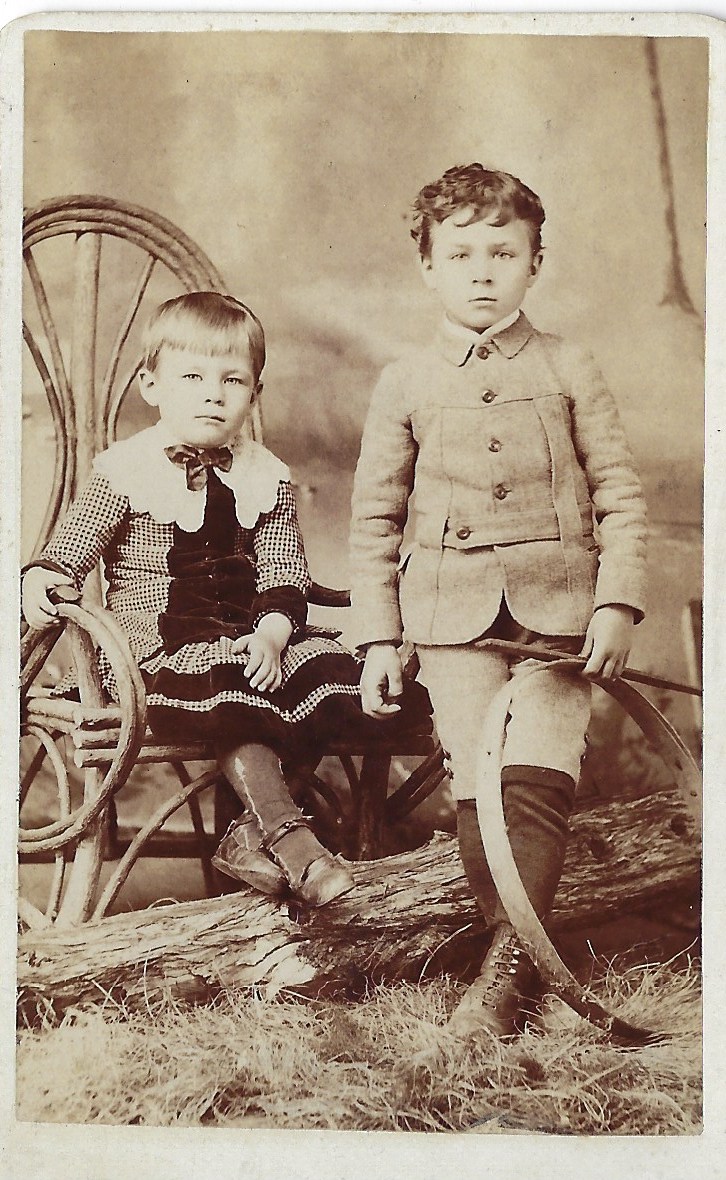

Photographs from the time also capture many young boys dressed in petticoats or a tunic and skirt, including this undated photo of two young boys. The younger boy is wearing a checked ensemble consisting of a tunic and a skirt trimmed in velvet while his older brother wears a wool suit consisting of a jacket worn with knickerbockers.

The transition from petticoats and dresses into short pants and then trousers took on symbolic importance as a rite of passage for a boy, but the age at which this occurred was a matter of individual choice,…as every mother is desirous that her little ones should be seen at their best, it will be her pride and pleasure to exercise her taste and judgement in this direction. As quoted by Clare Rose, “Age-related clothing codes for boys in Britain, 1850-1900,” Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion, vol. 2 (2015), pp.139.

Tailoring guides from this time reveal an age-related progression of attire for boys from petticoats indicated before age 3; jackets with skirts suggested for ages 3 to 6; tunic over trousers for boys aged 6-12; short wool jackets and trousers for ages 12-15; and suits for boys over age 15.

With the emergence of department stores and mass-production methods for clothing in the latter part of the nineteenth century, the options for boys expanded, but there was also a significant shift in ideals of masculinity that resulted in a marked restriction in the types of clothing and the colors available for boys. As historians including Jo Paoletti have observed, by about 1920, it was seen as highly inappropriate for boys to wear dresses, lace, ruffles, and other feminine-coded garments details or colors.

Renoir’s portrait of the Charpentier family reminds us that the dress codes that signal gender are linked to culture as well as a specific time and place in history. The idea that boys do not wear dresses dates back only about a century. Gender is a culturally specific notion — something that is learned rather than innate. Interpreting a painting such as this one by Renoir requires careful observation and reflection of the inherent biases of our own standpoint in culture.

Adapted and Excerpted from: Dr. Ingrid E. Mida, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Madame Charpentier and Her Children,” in Smarthistory, October 18, 2019, https://smarthistory.org/renoir-charpentier/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party,” in Smarthistory, November 12, 2015, accessed November 6, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/renoir-luncheon-of-the-boating-party/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

Edgar Degas

Degas painted La Belle Epoch– the beautiful era – which is the end of the 1800s.

Just by way of personal anecdote:

It’s la belle epoch and it’s generally pronounced “lah bell e pauk” but when said quickly it can sound like “la belly park.” As a student I heard the words during lectures, but since there were no text on the slides I never saw the words written and the term was never explained. Hearing “The Belly Park” was the subject of Degas’ paintings, I understood this to mean that Degas painted an exciting and new locale in the heart of Parisian society. The Belly Park – an electric and modern place in Paris somewhere.

Much to my eternal chagrin it was years later that I realized that “The Belly Park” was actually la belle epoch and it was a time, not a place. It was a way of life, not a location. It was a beautiful era, not an new development site in Paris.

Just as a technical aside: Degas wasn’t really an Impressionist at heart but don’t tell the Art Historians! Degas exhibited with the Impressionists and valued many of the same things they did, but his philosophy and approach to art was, in some ways, radically different than the other Impressionists. Whereas other Impressionists were interested in light, Degas was in many ways all about line and this becomes more and more clear in his Late Bathers series.

Degas used incredibly innovative compositions. Much of his approach was attributed to Japonisme, Japanese prints, and photography. He studied Japanese prints for their compositional techniques but also looked to photography as he felt it was a way to capture “movement in its exact truth.” Sometimes he would physically cut his canvases to get a better cropped look to relate more to the kind of composition a camera might capture and to look like it was an unplanned and free composition. But that was just artful cropping on Degas’ part. “No art was less spontaneous than mine,” Degas once said. Every aspect was carefully constructed and he rarely worked outside of his studio as he made endless preparatory drawings and studies for his works, sometimes making hundreds for a single final painting. He chose dancers and horses as his most frequent subjects because he wanted to convey the sense of beauty of movement and horses and dancers had perfect musculature and athleticism.

He, like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse who would come after him, could draw like an old master thanks to the advice given to him by Ingres in his youth – advice that he should draw and draw some more. The harshest critics had to congratulate him on his ability to draw and may have been able to accept, in a small way, the avant-garde because of his ties to the old masters techniques as well. Degas was a bit of a bridge between the old established ways of art and the new styles emerging in the later parts of the 1800s.

As he aged he began constructing perspective in ways that would be influential and important for the avant-garde that came after him.

Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “Edgar Degas, At the Races in the Countryside,” in Smarthistory, December 4, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/edgar-degas-at-the-races-in-the-countryside/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “Edgar Degas, The Dance Class,” in Smarthistory, November 25, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/edgar-degas-the-dance-class/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

Self-Reflection Question 9.1

- Baudelaire’s call to paint the ‘modern day hero’ was answered by the Impressionists. Do you feel that they were successful in this? Do you feel that there is still a place for Baudelaire’s ideas in the 21st century?