14 Chapter 9 – Claude Monet

The Changes in the Art of Claude Monet during the Times of his Mental Challenges

Kelsey Robinson

Audio recording of the full chapter can be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1RndV6kokslefxNXXDR5WCHc0c0jxUIA6/view?usp=sharing

Like poets with words, artists exhibit their ideas, feelings and emotions through their work. Claude Monet is no exception to this. Monet’s step into what would later be called “Impressionism” was also a step into a more stylization of the world as felt through the artist. Through time, feelings and emotions change and so do an artist’s portrayal of the world as a result. Monet went through some difficult times in his life that would ultimately have an effect on his work. Through this paper I am to demonstrate Claude Monet’s changes in his art as a result of the mental struggles he dealt with. In early August of 1867, Monet’s first son Jean was born in Paris.[1] By this point in his career while Monet had already been painting for over twenty years he was not completely financially stable and was struggling with money.[2] By 1868 he and his family had to move out of Paris and his son and future wife Camille stayed with friends in the country because of his money problems.[3] Money and the stress of a new child eventually caused him to break down mentally and attempted to commit suicide by jumping into the River Seine[4]. We can see that his mental health may have been declining since the birth of his son as seen through the subjects in his paintings after the birth. In The Cradle – Camille with the Artist’s son Jean (1867) Monet paints his son who was only a few months old in his light blue and flowered bassinet next to Camille. This is one of the first paintings we see of Monet’s son.

Before Jean was born we can see that Monet had been painting areas in Sainte-Adresse such as The Beach at Sainte-Adresse (1867) and some portraits such as Portrait of Ernest Cabade (1867). However after Jean’s arrival and after the Cradle Portrait we see that Monet begins to focus on still lives mostly consisting of Pears, Grapes and dead birds. French artist’s in the late 19th Century used the term Nature Mort to describe still lives as the term translates to “Dead Nature”.[5] Monet focused on these still life’s into 1868 and eventually began shifting back into landscapes where he focused on the snow and ice on the Seine in his two works: Ice Floes on the Seine at Bougival (1867-1868) and Snow on the River (1867-1868).

I believe that these works reflect Monet’s feelings at the time that would lead him to the act of attempting suicide and the struggles he was working through afterward. The cold and dreariness of his winter landscapes coupled with the still life’s that were most likely painted from his home represent his depression during this time. Monet worked primarily en plein air before finishing his pieces later in his studio[6]. Because of this painting technique it made Monet very aware of the colours and shadows that the land could take on, however instead of focusing on the colour that could be created during winter, he chose a more subdued colour pallet with less dramatic lighting. This shift away from brighter tones and dull overcast scenes may have been a reflection of Monet’s inner feelings. Eventually Monet began to paint with more bright colours and dramatic lighting, especially seen in works after Madame Gaudibert (1868) were his financial circumstances began to look up.[7] He began to paint with more varied pallets and more intense lighting and shadows. This would signal an increase in his value of life as he would marry the mother of Jean, and love of his life, Camille Doncieux in 1870 and paint Impression, Sunrise in 1874 which would begin the era of Impressionism in the art world.[8]

In 1878 Monet’s second son was born and due to already troubling health problems his wife Camille‘s health declined drastically and she died in 1879.[9] Monet over the years with Camille, he had painted numerus portraits of her, usually surrounded by bright or light colours but while on her deathbed Monet painted her portrait once again, Camille Monet on her Deathbed (1879). All of his colours are very muted and dull. Later in his life he would explain the emotions that he had felt while painting the work,

“I found myself staring at [my wife’s] tragic countenance, automatically trying to identify the sequence, the proportion of light and shade in the colors that death had imposed on [her] immobile face. Shades of blue, yellow, gray, and I don’t know what. . . . In spite of myself, my reflexes drew me into the unconscious operation that is but the daily order of my life. Pity me, my friend.”[10]

Monet describes how his artistic reflexes took him away from the moment and he studied her as if a simple landscape or another one of his casual portraits, and not of his now deceased wife who he loved dearly. The act of taking himself out of the moment suggest that his sadness was so great that he didn’t want to feel it. His artistic mind took control of the situation and made it seem like any other painting.

After this portrait he once again turned to painting still life’s or, Nature Morte “Dead Nature”[11]. Monet painted vases, fruits and dead pheasants, subjects that he could do from home, no doubt because of his sadness over the loss of his wife. I believe the still life’s were a way to continue painting while also staying in the comforts of one’s home. He painted still life’s until 1880 when he began to study landscapes again.[12] Much like after his suicide attempt in 1868, he didn’t go directly back to still life’s of grassy fields or colourful landscapes but instead focused on the harsh landscapes of winter for some time. Another example of Monet giving off a still and dull landscape through a mostly greyscale pallet. After so many years of painting, Monet would have understood the way light and colour effected the mood of a scene and known that no colour is neutral when it comes to the way it feels to the viewer.[13]

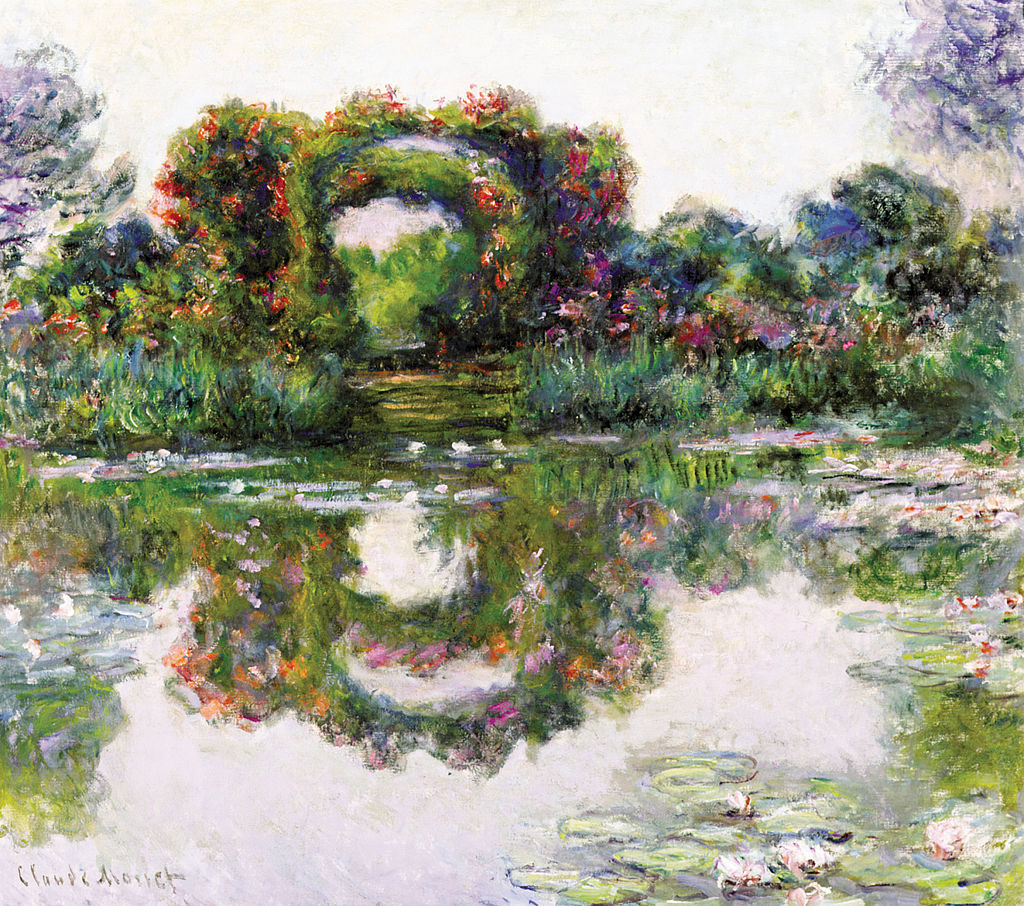

1912 Monet began to develop cataracts, a cloudy area that forms within the lens of the eye that obstructs ones sight.[14] Due to this, his work began to change dramatically. His delicate brushstrokes soon turned more abstract and chunky. We see this change through his multiple paintings of flowers from 1914 to 1917. [15]

Monet complained of muddy and weaker colours and even noting that his paintings were becoming darker as well.[16] There is no doubt that the effects of cataracts would also effect the artist’s mental health as this disease was taking away his ability to work. His work slowed as a result of this despondency as the work was not up to his standers due to his difficulty in seeing the true colours. Many of his paintings turned to more monochromatic blue tones as seen in The Japanese Bridge (1918-1924) and The Japanese Bridge (1917-1920) as a result of his cataract surgery, before drastically changing to vibrant red hues, most likely after another eye procedure sometime in 1923 or 1924, as seen in his multiple Japanese Bridge pieces from 1918-1924.[17] These red paintings also show more of the abstract style that Monet had taken on due to the poor eyesight. After some time and trying different methods to improve his vision, he was finally able to return to his preferred style with harmonious colours and gentle details, telling the viewers that his drastic shift to the harsh reds and hard brushstrokes were not an artistic decision but one that came out of necessity in order to adapt with his changing vision[18].

Claude Monet had struggled with many different emotion heavy events in his lifetime and his art during those times showed his mental progression and coping abilities. During financial struggles and the death of a loved one coupled with depression Monet exhibited more still life’s done in a personal space before transitioning back into landscapes through winter scenes that he painted as dull and still. Monet also exhibited his ability to work through disheartening results of cataracts and connected procedures which showed his thirst for painting as a lifestyle that helped him through tough times. The ways that Monet used light, colour and subject matter in his paintings were both a way for his fascination with light and colour to shine through as well as a way to exhibit his emotions and work through difficult times in his life. Monet, like many artists, view their art as not simply pretty pictures but a way to communicate their feelings about a subject with the world around them through varying means.

![By Claude Monet - musée Marmottan-Monet [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79058340](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Claude_Monet_-_Le_Pont_japonais_W1933_-_Mus%C3%A9e_Marmottan-Monet.jpg/1024px-Claude_Monet_-_Le_Pont_japonais_W1933_-_Mus%C3%A9e_Marmottan-Monet.jpg)

Bibliography

Aricchio, Laura, “Claude Monet (1840-1926).” The Met Museum. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, October 2004. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cmon/hd_cmon.htm.

Conway, Bevil R. “Color Consilience: Color through the Lens of Art Practice, History, Philosophy, and Neuroscience.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1251, no. 1 (March 2012): 77–94. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06470.x.

Gedo, Mary M. “Mme Monet on Her Deathbed”. JAMA 288, no. 8 (2002): 928. doi:10.1001/jama.288.8.928

Gruener, Anna. “The Effect of Cataracts and Cataract Surgery on Claude Monet.” British Journal of General Practice 65, no. 634 (2015): 254-255.

Hajar, Rachel. “Eye Disease and Visual Perspective in Painting.” Heart Views 17, no. 1 (January 2016): 41. https://search-ebscohostcom.ezproxy.ardc.talonline.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=115557633.

“Jean Monet (Son of Claude Monet),” Wikipedia. April 24, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Monet_(son_of_Claude_Monet)

“List of Paintings by Claude Monet,” Wikipedia. October 29, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_paintings_by_Claude_Monet

“Monet, Khalo and Van Gogh, Their Art and Mental Illness.” Bipolar Disorders 20 (March 2, 2018): 37–38. doi:10.1111/bdi.25_12616.

Nikolić, Ljubiša, and Vesna Jovanović. “Cataract, Ocular Surgery, Aphakia, and the Chromatic Expression of the Painter Jovan Bijelić.” Vojnosanitetski Pregled: Military Medical & Pharmaceutical Journal of Serbia 73, no. 11 (November 2016): 1003–9. doi:10.2298/VSP150313126N.

Nicolas Pioch, “Monet, Claude” WebMuseum. September 19, 2002. https://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/monet/early/gaudibert/

Stewart, Mary. Launching the Imagination. New York: McGraw Hill Education, 2019.

- “Jean Monet (Son of Claude Monet),” Wikipedia. April 24, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Monet_(son_of_Claude_Monet) ↵

- “Monet, Khalo and Van Gogh, Their Art and Mental Illness.” Bipolar Disorders 20 (March 2, 2018): 37–38. ↵

- “Jean Monet (Son of Claude Monet),” Wikipedia. April 24, 2020. ↵

- “Monet, Khalo and Van Gogh, Their Art and Mental Illness.” Bipolar Disorders 20 (March 2, 2018): 37–38. ↵

- Mary M. Gedo, “Mme Monet on Her Deathbed”. JAMA 288, no. 8 (2002) ↵

- Bevil R. Conway “Color Consilience: Color through the Lens of Art Practice, History, Philosophy, and Neuroscience” ↵

- Nicolas Pioch, “Monet, Claude” WebMuseum. September 19, 2002. https://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/monet/early/gaudibert/ ↵

- Laura Aricchio, “Claude Monet (1840-1926).” The Met Museum. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, October 2004. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cmon/hd_cmon.htm. ↵

- Mary M. Gedo, “Mme Monet on Her Deathbed”. JAMA 288, no. 8 (2002) ↵

- Mary M. Gedo, “Mme Monet on Her Deathbed”. JAMA 288, no. 8 (2002) ↵

- Mary M. Gedo, “Mme Monet on Her Deathbed”. JAMA 288, no. 8 (2002) ↵

- “List of Paintings by Claude Monet,” Wikipedia. October 29, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_paintings_by_Claude_Monet ↵

- Mary Stewart, “Launching the Imagination” (New York; McGraw Hill, 2019) 58 ↵

- Rachel Hajar, “Eye Disease and Visual Perspective in Painting.” Heart Views, 17, no. 1 (2016) 41. ↵

- “List of Paintings by Claude Monet,” Wikipedia. October 29, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_paintings_by_Claude_Monet ↵

- Anna Gruener, “The Effect of Cataracts and cataract surgery on Claude Monet.” British Journal of General Practice, 65, no. 634 (2015) ↵

- Nikolić, Ljubiša, and Vesna Jovanović. “Cataract, Ocular Surgery, Aphakia, and the Chromatic Expression of the Painter Jovan Bijelić.” Vojnosanitetski Pregled: Military Medical & Pharmaceutical Journal of Serbia 73, no. 11 (November 2016): ↵

- Anna Gruener, “The Effects of Cataracts and cataract Surgery on Claude Monet.” ↵