5 Chapter 4 – British Romanticism and the Picturesque Tradition

Britain

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- Identify the works of Benjamin West, Henry Fuseli, William Blake – British Romantics

- Explain the six types of painting categories and how they generally ranked in Britain as compared to France at the same time

- Define the Picturesque Tradition and Picturesque Composition

- Recognize and explain the satirical works of Thomas Rowlandson

- List and define the 7 categories of landscape painting

- Recognize the works of J.M.W. Turner, John Martin, and John Constable – the British Landscape Romantics

Chapter opening in audio

Let’s start this chapter with something really fun. Dictionary definitions!

If you see the word ‘Sublime’ what do you generally see the word to mean? (All jokes about less than perfect limes aside, I mean.)

Oxford Lexico defines ‘sublime’ as:

Merriam-Webster defines it as:

“a: lofty, grand, or exalted in thought, expression, or manner

b: of outstanding spiritual, intellectual, or moral worth

c: tending to inspire awe usually because of elevated quality (as of beauty, nobility, or grandeur) or transcendent excellence.

2: beautiful or impressive enough to arouse a feeling of admiration and wonder.”[2]

Webster’s 1828 dictionary defines it as:

“1. High in place; exalted aloft.

2. High in excellence; exalted by nature; elevated.

3. High in style or sentiment; lofty; grand.

4. Elevated by joy; as sublime with expectation.

5. Lofty of mein; elevated in manner.

SUBLI’ME, noun A grand or lofty style; a style that expresses lofty conceptions.”[3]

In Wikipedia’s entry regarding the Sublime in philosophy:

“What is “dark, uncertain, and confused” moves the imagination to awe and a degree of horror. While the relationship of sublimity and beauty is one of mutual exclusivity, either can provide pleasure. Sublimity may evoke horror, but knowledge that the perception is a fiction is pleasureful.”[4]

“Burke defines the sublime as “whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger… Whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror.” Burke believed that the sublime was something that could provoke terror in the audience, for terror and pain were the strongest of emotions. However, he also believed there was an inherent “pleasure” in this emotion. Anything that is great, infinite or obscure could be an object of terror and the sublime, for there was an element of the unknown about them.”[6]

In his book The World as Will and Representation from 1818, Arnold Schopenhauer outlined the difference between Beauty and the Sublime as follows:

Feeling of Beauty – Light is reflected off a flower. (Pleasure from a mere perception of an object that cannot hurt observer).

Weakest Feeling of Sublime – Light reflected off stones. (Pleasure from beholding objects that pose no threat, yet themselves are devoid of life).

Weaker Feeling of Sublime – Endless desert with no movement. (Pleasure from seeing objects that could not sustain the life of the observer).

Sublime – Turbulent Nature. (Pleasure from perceiving objects that threaten to hurt or destroy observer).

Full Feeling of Sublime – Overpowering turbulent Nature. (Pleasure from beholding very violent, destructive objects).

Fullest Feeling of Sublime – Immensity of Universe’s extent or duration. (Pleasure from knowledge of observer’s nothingness and oneness with Nature).

Excerpted from: Ben Pollitt, “John Martin, The Great Day of His Wrath,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/martin-the-great-day-of-his-wrath/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

It’s pretty clear that something that is ‘sublime’ is more than just a really good tasting piece of pie when it comes to the Arts. The idea of the Sublime often relates to exciting, emotional, and uplifting vistas – like mountain scenes where unbridled nature sits in unbending grandeur in the face of puny human existence. But it is also the idea of something experiential. It calls to mind the reaction in the mind and soul of the viewer as they look at something bigger and more powerful than themselves. And in this understanding of the all-enveloping nature of the natural scene before them the viewer feels a kind of horror.

America’s Raphael – Benjamin West

Benjamin West was known in Britain as America’s Raphael, but don’t worry, this didn’t go to his head. He only named his first born son Raphael, but that’s probably just a coincidence. Right?

Born in the U.S, West claimed in Britain that he was largely self taught. The story he told of his art upbringing reads more like an origin story of epic feats of mastery than a simple artist’s training. His story was that he taught himself everything he knew after the American Indians taught him how to mix pigments and his mother’s praising kiss of a childhood drawing motivated him to make more art. Stories like this make good tales but they really build into the idea of the artist as genius, sprung full formed from Creativity’s head. It’s not that West’s story is likely false. It is possibly true, but when you hear stories like that take them with a good dose of skepticism and recognize that while heroes do exist, they often aren’t nearly as heroic as we want them to be. Lest it seem that we are underselling the hurdles that West’s early-American background caused, it should definitely be highlighted that West did not present himself as a well-schooled man. He was born in Pennsylvania and when, later in life, he was president of the British Royal Academy, he could barely spell. But it really does beg a question: how did a young artist who swore he had immense lack of access to European-type education find his way into the very highest levels of British society?

Well, the answer lies in, well, lies.

As Dr. Brian Zygmont explains;

In 1760, two wealthy Philadelphian families paid for the young Benjamin West’s passage to Italy so he could learn from the great European artistic tradition. He was only 21 years old. He arrived in the port of Livorno during the middle of April and was in Rome no later than 10 July. West remained in Italy for several years and moved to London in August of 1763. He found quick success in England and was a founding member of the Royal Academy of Art when it was established in 1768. West was clearly intoxicated by the cosmopolitan London and never returned to his native Pennsylvania. West’s fame and importance today rest on two important areas:

- West as teacher

West taught two successive generations of American artists. All of these men travelled to his London studio and most returned to the United States. Indeed, a list of those who searched out his instruction comprises a “who’s who” list of early American artists, - West as history painter

If his role as a teacher was the first avenue to West’s fame, surely his history painting is the second. Of the many he completed, The Death of General Wolfe is certainly the most celebrated.

In this painting, West departed from conventions in two important regards. Generally, history paintings were reserved for narratives from the Bible or stories from the classical past. Instead, however, West depicted a near-contemporary event, one that occurred only seven years before. The Death of General Wolfe depicts an event from the Seven Years’ War (known as the French and Indian War in the United States), the moment when Major-General James Wolfe was mortally wounded on the Plains of Abraham outside Quebec.

Secondly, many—including Sir Joshua Reynolds and West’s patron, Archbishop Drummond—strongly urged West to avoid painting Wolfe and others in modern costume, which was thought to detract from the timeless heroism of the event. They urged him to instead paint the figures wearing togas. West refused, writing, “the same truth that guides the pen of the historian should govern the pencil [paintbrush] of the artist.”

Yet despite West’s interest in “truth,” there is little to be found in The Death of General Wolfe. Without doubt, the dying General Wolfe is the focus of the composition. West paints Wolfe lying down at the moment of his death wearing the red uniform of a British officer. A circle of identifiable men attend to their dying commander. Historians know that only one—Lieutenant Henry Browne, who holds the British flag above Wolfe—was present at the General’s death.

Clearly, West took artistic license in creating a dramatic composition, from the theatrical clouds to the messenger approaching on the left side of the painting to announce the British victory over the Marquis de Montcalm and his French army in this decisive battle. Previous artists, such as James Barry, painted this same event in a more documentary, true-to-life style. In contrast, West deliberately painted this composition as a dramatic blockbuster.

This sense of spectacle is also enhanced by other elements, and West was keenly interested in giving his viewers a unique view of this North American scene. This was partly achieved through landscape and architecture. The St. Lawrence River appears on the right side of the composition and the steeple represents the cathedral in the city of Quebec. In addition to the landscape, West also depicts a tattooed Native American on the left side of the painting. Shown in what is now the universal pose of contemplation, the Native American firmly situates this as an event from the New World, making the composition all the more exciting to a largely English audience.

Perhaps most important is the way West portrayed the painting’s protagonist as Christ-like. West was clearly influenced by the innumerable images of the dead Christ in Lamentation and Depositions paintings that he would have seen during his time in Italy. This deliberate visual association between the dying General Wolfe and the dead Christ underscores the British officer’s admirable qualities. If Christ was innocent, pure, and died for a worthwhile cause—that is, the salvation of mankind—then Wolfe too was innocent, pure, and died for a worthwhile cause; the advancement of the British position in North America. Indeed, West transforms Wolfe from a simple war hero to a deified martyr for the British cause. This message was further enhanced by the thousands of engravings that soon flooded the art market, both in England and abroad.

Excerpted and adapted from: Dr. Bryan Zygmont, “Benjamin West, The Death of General Wolfe,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/benjamin-wests-the-death-of-general-wolfe/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

“Noble Savage” – emergence of a stereotype in audio

“Noble Savage” – emergence of a stereotype

If you look up the phrase “Noble Savage” on Wikipedia, a detail of Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe pops up. The depiction of the tattooed North American Indian who calmly contemplates the noble sacrifice of Wolfe’s martyrdom is a philosophical stereotype that occurs in art frequently, but is especially popular in art of the 1800s in Europe.

Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant use movies to explain the concept of the “noble savage”:

One of the defining concepts of primitivism is that of the “noble savage,” an oxymoronic phrase often attributed to the eighteenth-century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, although he never used it. Now recognized as a stereotype, the noble savage is a stock character of literature and the arts who may lack education, technology, and cultural refinement, but who lives according to universal natural law and so is inherently moral and good. Many popular books and films exemplify the concept of the noble savage, including Tarzan, The Gods Must Be Crazy, Dances With Wolves, and Avatar.

In Avatar, for example, the indigenous, blue-skinned Na’vi are technologically inferior to the humans who come to mine their Eden-like world for resources, but they are morally superior and closer to nature. Although the Na’vi are loosely based on Native Americans, it is important to remember that the primitivist concept of the noble savage is essentially mythic, not documentary.

Excerpted from: Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant, “Primitivism and Modern Art,” in Smarthistory, March 7, 2020, accessed September 19, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/primitivism-and-modern-art/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC:BY-NC-SA

Where Benjamin West’s earlier work was very influenced by the Neo-Classical tradition, his later works fit firmly within the parameters of Romanticism. Death on the Pale Horse is a Romantic Biblical painting: it has all the stormy, gothick, impetuous, terrifying, titillating elements of a Gothick Sublime painting. And to create a fully immersive viewing experience, it was also absolutely enormous. Almost 15 feet by 25 feet!

The story depicted is based on the vision in the Book of Revelation in chapter 4, verse 8:

“And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him. And power was given unto them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth.”

Now this painting is called Death on the Pale Horse, but really all four horses of the Apocalypse are there. The White horse with the ruler. The Red horse with War. The black horse with the balances in his hand – Famine.

Death on the Pale Horse was a painting hated by the king of England, but loved by West. [7] The king of England found it repulsive its chaos, while Jacques-Louis David who saw it in Paris 1802, said it was a cheap replica of Peter-Paul Rubens work for the 1600s.[8] Because of the French Revolution Romanticism came later to France than it did to England and therefore this Romantic style of painting would have seemed horribly emotional compared to the Neo-Classical work so honoured in France. The first version of this painting by West was completed the same year as David’s Oath of Horatii.[9]

Henry Fuseli in audio

Henry Fuseli

In 1755 a horrendous earthquake shook Lisbon and shattered the lives of countless people. The sheer force of this quake defied logic and explanation; its unimaginable affects cracked the smooth surface of [the] common-sense” of an entire era founded on common sense, rationality and science.[10] “It is arguable that the Romantic Movement first showed itself as an expression of fear” and this fear is extremely evident in one of the first Romantic paintings – Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare.“[11] Fuseli’s painting is a perfect specimen to showcase the Romantic Movement’s themes – specifically the themes of iconography, sexual desire, fear and the irrationality in dreams.[12] More specifically, The Nightmare reveals Fuseli’s personal themes of desire, love’s betrayal and the mysteries of his psyche.

It is important to note, before analyzing Fuseli’s The Nightmare, that there are two versions of this painting. Both were painted by the same artist and are titled the same thing and contain very similar imagery. However, the second version, from 1791, contains some

iconographical significant differences from the 1781 version. To speak of one of these versions is to also consider the other. To speak of meaning in one painting requires comparison and corroboration from the other.

According to some critics, The Nightmare holds social and political implications; however, Frederick Antal the author of Fuseli Studies, considers Fuseli to not have been sufficiently politically- minded” to consciously convey a political message in his art.”[13] Though it is true that Fuseli’s image was used by many political caricaturists after its exhibit in the 1783 Royal Academy exhibition, Fuseli was likely not expressing a political view as much as he was exorcising private demons and psychological obsessions.

The title is one of the first things to consider when beginning to dissect the meaning of this work. In the 1700’s a dream that was classified as a ‘nightmare’ was a special sort of dream that is distinctly different from the catch-all meaning of the term today.[14] The term comes from the combining of night and the word ‘mara‘ – which was a spirit that tormented and suffocated sleepers. A nightmare, in Fuseli’s time, was clinically defined as a type of sleep paralysis, when the “principle symptom is someone or something sitting on the chest.”[15]

The Nightmare is a painting that depicts a dream. True to its era, it shows both the person dreaming and the dream they are experiencing. A woman dressed in a diaphanous white robe or night dress lies prostrate across and almost off the bed. The room is one that would have been considered to be conservatively contemporary during the time it was painted – the Rococo era.[16] Through an opening in the bed-chamber curtains a horse head appears, looking into the room with strangely globular, dead eyes. On the woman’s mid-section sits a strange and horrible creature. This creature, in the 1781 rendition, is a horrible ape-man that casts the shadow of an owl. In the 1791 version, this creature has changed into something even more demonic – a cat-ape creature that is clenching a pipe between his hideously grinning teeth. While these entities are in the room with this dreaming, sleeping woman they are not what she is seeing in her dream – they are symbols of the terror and suffocating oppression which she feels.”[17]

A viewer of The Nightmare knows that these creatures are not what the sleeper is seeing because of the furniture in the painting and the position of the sleeping woman. The mirror, in the 1791 version, has been moved so that the viewer can see that it holds no reflection. Because it holds no images, even though it is angled in a way “that could reflect the figure of the incubus squatting on the sleeper’s stomach”, the viewer is to understand that this creature is not present in the corporeal world.”[18] As well, the incorporation of a mirror into a nightmare painting would reference the literary work of the English writer, John Locke (whom Fuseli would be aware of), who stated that those who do not remember their dreams are like looking-glasses they receive a variety of images…but retains none.”[19] The final clue that these creatures are not being seen by the sleeper is her position across the bed. Her position is such, that even if her eyes were to open she could see neither horse nor demon.”[20]

An important part of the painting that the viewer can not see when viewing the 1781 version, is the unfinished portrait of a woman that is on the back of the canvas. This portrait is believed to be the portrait of Anna Landolt, with whom Fuseli fell hopelessly in love.[21] Due to this woman’s presence on the back of such a violently erotic painting, it is important to understand her relationship with Henry Fuseli. While Fuseli had been in Zurich visiting a friend, he had met his friend’s niece – Anna. Unfortunately, for Fuseli, she was already engaged to a merchant and it is unclear as to what extent she was aware of Fuseli’s attraction, as he was naturally very shy and below her in economic status.[22] As well, letters that reveal his passion are all addressed to Anna’s uncle. In one of the letters, Fuseli relates an erotic dream that he had dreamt of Anna and himself stating that she was now completely his and anyone who got in the way was committing adultery.[23] Fuseli had worked himself into a fever pitch that seems to have culminated with The Nightmare. It is not a broad jump to consider the woman in The Nightmare to be “a projection of Anna Landolt.”[24] As Nicolas Powell, author of Fuseli: The Nightmare, relates that even if the woman on the back of the canvas is not Anna Landolt, it is evident that “The Nightmare was inspired by his hopeless passion for her, the painting is deeply impregnated with Fuseli’s obsessive, ambivalent sexual feelings.”[25] Because of Fuseli’s feelings for Anna and his dreams about her, The Nightmare is a “deliberate allusion to traditional images of Cupid and Psyche meeting in her bedroom at night; here the welcomed god of love has been transformed into a demonic incubus of erotic lust.”[26]

Henri Fuseli part 2 in audio

The horse, which the creature rode into the room on, is an ancient and important symbol. A horse in a painting is “associated with sexual energy, impetuous desire or lust,” and this is especially true in Fuseli’s painting.[27] It is an “ancient masculine symbol of sexuality” that is often “associated with the devil.”[28] A very noticeable difference between the 1781 and the 1791 paintings is colour of the horse – in the early version it is a dark horse and in the later it is white. The black horse is a representation of death, while the white horse is “a solar symbol of light, life and spiritual illumination.”[29] The change in colour of the horse could be a manifestation of the changing ideas of the Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) group, with which Fuseli was associated. By the beginning of the 1780’s, Sturm und Drang had become aware of new theories of electricity and electromagnetic impulses from books that had been published.”[30] “The moment of Terror” that the Romantics sought to depict had become a “violent electrical discharge, with its accompanying light and smell.[31] Thus, on a symbolic level, a horse that was the black of death, would become white – a symbol of light. On a less theoretical level, during a shot of lightning, even things that had previously been a very dark colour will reflect enough of the light to appear to be a ghastly and ghostly white colour.

It is not completely unthinkable to see the second version of the painting to be painted in the light of a sheet lightning strike.[32] The first version of the painting is rich with colour, especially red, but everything contains what could be perceived as the ‘correct’ sort of colour. However, the second version is almost completely monochromatic. With the exception of the tiniest bit of pinkish pigment in the sleeper’s skin, the entire painting is shades of grey. This sudden shift into a monochromatic palette could be easily understood to be due to Fuseli’s and Sturm und Drang‘s ideas of electricity and lightning.

This reference to electricity would also refer back to the clinical definition of a nightmare. While the nightmare was a form of sleep paralysis, the treatise on electricity had found that a paralyzed limb could be made to move through the application of an electrical

shock.”[33] Thus, a painting of a nightmare with the light of electrical lightning would be a circular reference to the new sciences of the time.

As mentioned before, the first version of the painting is alive with the colour red. It is almost the only colour in the room other than white. Fuseli’s use of this colour was not a simple stylistic choice. In his Aphorisms on Art, from 1818, Fuseli stated that colors can have stimulating or relaxing affects, much like music.[34] Of the colour red, in particular, Fuseli said that “scarlet or deep crimson rouses [and] determines.”[35] Symbolically, red was an “active and masculine colour of …energy, aggression, danger…emotion, passion.. [and] strength”; it was the colour most associated with sexuality and was “the colour of arousal”; it is important then, to notice that the woman is completely encircled by red fabric.[36] It is the colour of the curtains as well as the colour of the blanket that is under her. However, it is interesting to note that while she is engulfed in red, the only colour to actually touch her in the 1781 version is white – the colour of purity. Fuseli’s aggressive desires, while encompassing her, have no impact on the actual state of her pureness in his eyes.

The female sleeper is completely surrounded and overtaken by masculine sexuality. She is encompassed by the masculine, sexual colour red. The masculine and sexual image of the incubus sits on her, overcoming her with his gothick allure and hideousness.[37] The horse is what brought the incubus to her and it also is a male sexuality symbol. To further show masculine sexuality, the 1791 version of the painting has the incubus playing a pipe or flute, which is a phallic symbol of masculine sexuality.[38] Her passive posture of sexual acceptance shows that she is completely overcome by this overwhelming masculine presence.[39] A circumstantial detail of interest is the sleeper’s single adornment on her nightgown. A tiny yellow heart is pressed against her chest. Yellow is sometimes seen to be the traditional colour of betrayal, cowardice, and disloyalty- could this be a reference to her ‘betraying heart’?

Fuseli’s The Nightmare is a painting that shows the desires of its creator, reveals the betrayal of unrequited love and contains the mysteries of his psyche.[40] It shows his sexual lust and passion for Anna Landolt and reveals his angst over the un-reciprocated desires. It displays his sadistic/masochistic predilection of dominant and submissive relationships – something that can also be seen in his drawings.[41] It also shows the emotional irrationality and fear so prevalent in Romantic painting. The Nightmare was considered to be a highly disturbing painting in its time and it “continues to hold the modern observer.because it represents an everyday – or every night- phenomenon in terms which are instantly comprehensible”; it would seem that Fuseli made a raid on what Jung was to call the ‘collective unconscious’.”[42]

William Blake section audio

William Blake

William Blake is famous today as an imaginative and original poet, painter, engraver and mystic. But his work, especially his poetry, was largely ignored during his own lifetime, and took many years to gain widespread appreciation.

The third of six children of a Soho hosier, William Blake lived and worked in London all his life. As a boy, he claimed to have seen ‘bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars’ in a tree on Peckham Rye, one of the earliest of many visions. In 1772, he was apprenticed to the distinguished printmaker James Basire, who extended his intellectual and artistic education. Three years of drawing murals and monuments in Westminster Abbey fed a fascination with history and medieval art.

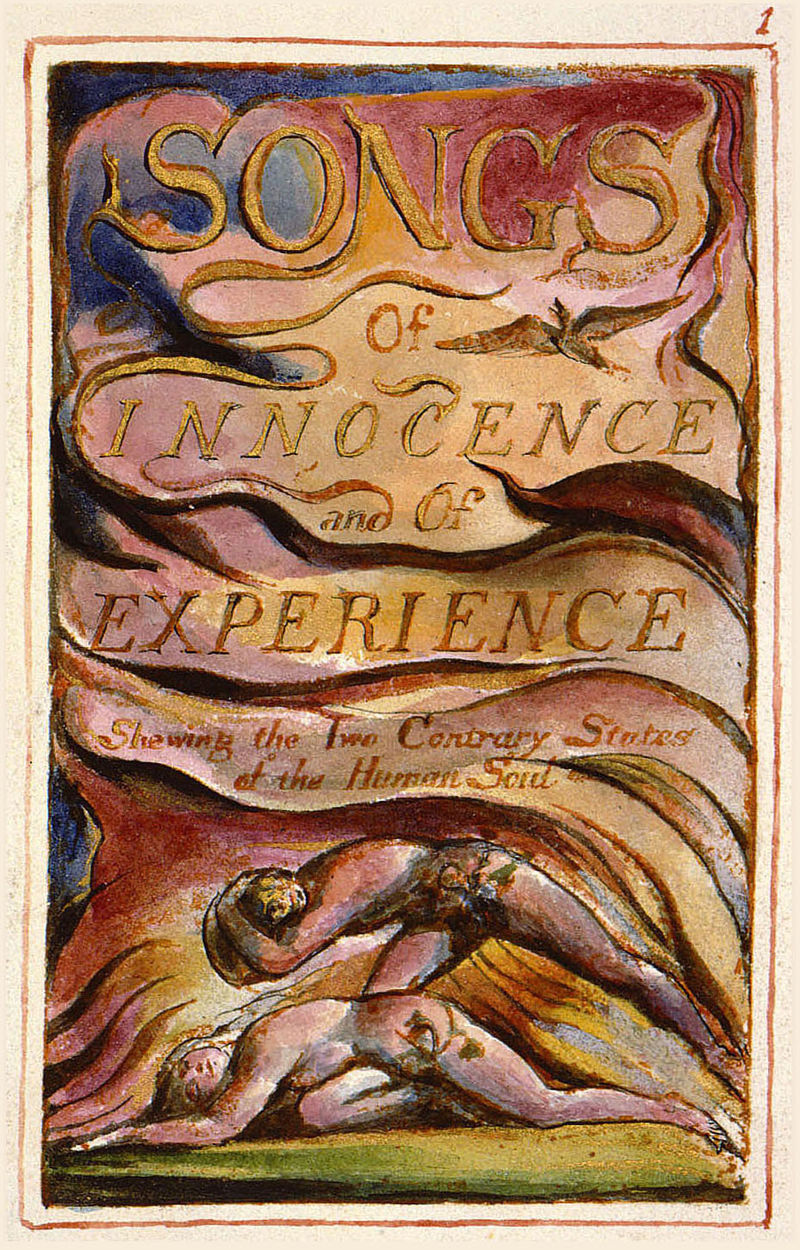

In 1782, he married Catherine Boucher, the steadfast companion and manager of his affairs for the whole of his checkered, childless life. He taught Catherine to read and write, as well as how to make engravings. Much in demand as an engraver, he experimented with combining poetry and image in a printing process he invented himself in 1789. Among the spectacular works of art this produced were ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’, ‘Visions of the Daughters of Albion’, ‘Jerusalem’, and ‘Songs of Innocence and Experience’.

Excerpted from: “William Blake,” in LumenLearning: English Literature II, accessed September 19, 2020, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/atd-bhcc-englishlit/chapter/biography-william-blake/

Lumen Learning material is shared via the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (CC: BY 4.0)

Blake experimented with relief etching, a method he used to produce most of his books, paintings, pamphlets and poems. The process is also referred to as illuminated printing, and the finished products as illuminated books or prints. Illuminated printing involved writing the text of the poems on copper plates with pens and brushes, using an acid-resistant medium. Illustrations could appear alongside words in the manner of earlier illuminated manuscripts. He then etched the plates in acid to dissolve the untreated copper and leave the design standing in relief (hence the name).

This is a reversal of the usual method of etching, where the lines of the design are exposed to the acid, and the plate printed by the intaglio method. Relief etching was intended as a means for producing his illuminated books more quickly than via intaglio. The pages printed from Blake’s plates were hand-coloured in watercolours and stitched together to form a volume. Blake used illuminated printing for most of his well-known works, including Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Book of Thel, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Jerusalem.[43]

Excepted and adapted from: Wikipedia, September 19, 2020, s.v. “William Blake.”

Wikipedia material is shared via a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License CC: BY SA license

British Landscape Painting in audio

British Landscape Painting

British Landscape painting has its roots in land ownership. Before the era of democratized literacy, new land owners would commission painters to paint their land – the painting would then be kept as a land deed. Sometimes the land owner and his family would be included in the painting foreground, but these paintings were always about the reproduction of the land owner’s boundaries (not unlike aerial photos of farmland in the twentieth century). When military endeavours came to Canada, landscape painters – both in the French and British troops – were part of the military and many high ranking officers were highly trained in landscape sketching. Part of this was that old tradition of ownership via reproduction, but also there was the more practical need for record of terrain to help with map making.

Eventually landscape painting in Britain was no longer a tool – it was considered an art form and it was a perfect vehicle for Romanticism and the Sublime. But bear in mind that the old idea that ‘what you see you own’ was (and is) quite prominent in the British perspective of the world and no matter how dramatic a Romantic Landscape may have been, that cultural aspect was often present in some way.

Watercolour made for the perfect medium for painting on the spot. Watercolour painting rose to prominence in the 1700’s. The best academies, particularly the British Woolwich Military Academy, placed great emphasis on introducing field officers to drawing and painting, a vital talent when planning attacks or sieges. These men, invariably from the upper classes, took this skill into their civilian lives and the idea of keeping a personal sketching or painting journal became part of the expected accomplishments of a classical education.

The Grande Tour

The Picturesque

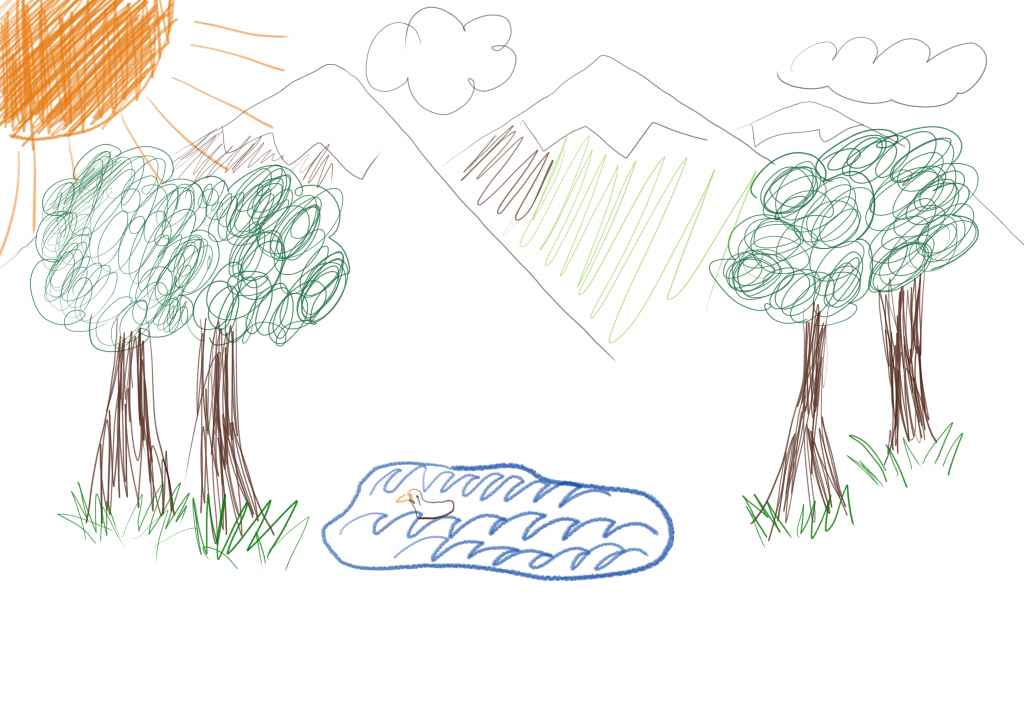

It was late in the 1700s that Rev. William Gilpin used the term ‘Picturesque’ to describe a kind of painting – previously the word had meant ‘like a picture’ but in Gilpin’s usage it had a prescribed and particular meaning. For Gilpin, the picturesque fell somewhere between beautiful and sublime, and both texture and composition were important in a “correctly picturesque” scene. According to his prescription, the texture of the scene should be rough, intricate, varied, or broken, and without obvious straight lines. The composition could work as a unified whole, incorporating several elements: a dark foreground with untamed growth and rocks or a front screen or side screens of trees or bushes or other foliage element, a brighter middle distance usually consisting of some kind of body of water but not always, and at least one further, less distinctly depicted distance. A ruin of some kind would add interest, but was not necessary. A low viewpoint, which tended to emphasize the Sublime, was always preferable to a perspective from a high vantage point (although this rule was open to interpretation).The rules generally meant:

- the foreground should be rocky and unkempt, and if not, then at least darkened.

- the sides should have trees framing, possibly a screen of trees creeping into the foreground.

- the mid-ground should be bright, with water if possible. Maybe some ruins or possibly some calm animals or people – never working hard, mostly in leisure. If working then working picturesquely.

- the background should contain aerial perspective of hills or mountains.

- All should be unkempt and untouched looking – the wild and foreboding wilderness or the quaint forgotten past. Never manicured, never contrived.

Which sounds like a strict set of rules that would have fallen out of fashion, right? Yet, all these landscape photos follow many of the rules of the Picturesque. While it is true that not every landscape photo or painting in existence follows a Picturesque composition, many of the landscapes that, even in the twenty-first century, are considered the most ‘beautiful’ follow Rev. Gilpin’s suggestions.

This is a passage from a book, printed in Britain in 1827 by a woman named Jane Webb Loudon, a friend of John “Mad” Martin who we’ll get to later, set in the far flung future (2126) where women of the royal court wear trousers and things are run by steam (yes, this is sort of a steampunk book – although not so much about the steam as about galvanized mummies) called The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century. Which isn’t the sort of book you’d expect to have much in common with the picturesque tradition, and yet…

“The windows of the library opened to the ground, and looked out upon a fine terrace, shaded by a verandah, supported by trelliswork, round which, twined roses mingled with vines. Below, stretched a smiling valley, beautifully wooded, and watered by a majestic river winding slowly along; now lost amidst the spreading foliage of the trees that hung over its banks, and the shining forth again in the light as a lake of liquid silver. Beyond, rose hills majestically towering to the skies, their clear outline now distinctly marked by the setting sun, as it slowly sank behind them, shedding its glowing tints of purple and gold upon their heathy sides; whilst some of its brilliant rays even penetrated through the leafy shade of the veranda, and danced like summer lightning…”[44]

Sound like something you’ve seen recently?

Maybe the photos, the description in an old steampunk book, and some old paintings don’t convince you that the Picturesque is still a well-loved and culturally relevant compositional device. Perhaps you feel that these examples have been hand-picked (they were). But consider, if you will, what a child draws when given the opportunity. Children will draw what they experience and what they are familiar with, so the compositions they will create by default are heavily influenced by the culture and environment they grow up in.

The Picturesque part 2 in audio

When I was a child, this was the kind of drawing I would draw when I wasn’t sure what to draw next (this is assuming I wasn’t ritualistically drawing all my family over and over like they were in peril of forgetting their children or sibling and also in the unlikely event that I had grown tired of drawing brides in fancy dresses). I grew up with the Rocky Mountains just on the edge of the horizon so my attempts at grand vistas always included them. However, children who grow up without mountains as part of their environment tend to not include mountains and will instead include rolling hills, or some other device to denote the horizon, but utilizing elements of the Picturesque appears to be common. It seems that many children in Canada, when drawing the landscape, will default to using Picturesque compositional devices. Is this because the Picturesque is an instinctual way to communicate the land? No, not at all. It is largely because of Canada’s connection to British traditions. Every free photo calendar from a grocery store or bank will have at least a few Picturesque landscape photos. So many inspiring computer wallpapers, nearly all the ‘good’ vacation photos, and a variety of moving Canada tourism commercials in Canada use this composition. As a former British colony some cultural communication devices don’t die when legal ties are cut.

Canada has a tradition of using the land as a way to bind the country together. Landscape painting was used as a way to seem to legally claim the lands that had been taken in breach of British law. Landscape painting was used as a way to call the diverse and widespread settlers of the country together. Landscape painting was used as a way to advertise the region’s riches of natural resources and alluring adventures. The Group of Seven were a group of seven settler artists (plus Tom Thompson) with the purpose of creating Canadian art. This ‘new’ Canadian art had to be:

- “Autochthonic” – Native. Born from the Land itself. Words like “Indigenous” and “Native” were words used to describe this new national art,

- Must be free of outside, European influences,

- First Nations must never appear (nor can French-Canadians), and as a result

- The group travelled by box car, although they were all more or less financially stable, on the newly completed CPR railway across Canada as a service to the government – ‘documenting’ the ‘wilderness.’[45]

Over a hundred years after Rev. Gilpin codified the rules of the Picturesque, on an entirely different continent, those same rules were being applied over and over to make highly marketable art and to strengthen cultural heritage.

Hierarchy of Painting Genres in Britain

Remember how painting genres were dealt with in a hierarchical order in France? It wasn’t much different in England – History painting was still at the top, Still Life at the bottom, Landscape and Portrait and Genre in the middle, but before this sudden interest in nature and the British Landscape, the lowly landscape painting was only slightly better than the painting of somebody’s dog.

- Painting Hierarchy

- Historical Painting

- Portrait

- Genre

- Landscape

- Animal

- Still Life

Self-Reflection Question 4.1

Create a time-line of the following events that have been covered and/or occurred during the time covered in chapters 1 through 4:

- French Revolution

- American Revolution

- Empire Style

- Neo-Classicism

- Bourbon Restoration Period

- French Romanticism

- Napoleonic Era

- Georgian Period

- Industrial Revolution

- Rococo

- British Romanticism

- Victorian Period

John Constable section audio

John Constable

Constable was born in East Bergholt, Suffolk and was largely self-taught. As a result, he developed slowly as an artist. While most landscapists of the day travelled extensively in search of picturesque or sublime scenery, Constable never left England. He had many children and his wife died; he had financial troubles and stayed close to home to take care of his family. By 1800 he was a student at the Royal Academy schools but only began exhibiting in 1802 at the Royal Academy in London. His paintings were not well respected in Britain, even as Romantic Landscape painting was becoming popular. But later at the Paris Salon (where his British Landscape won the gold medal). He later influenced the Barbizon School, the French Romantic movement, and the Impressionists.

Watch a video that analyzes Constable’s The Haywain here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PVmczLwlU00&feature=youtu.be

Studying the English painter John Constable is helpful in understanding the changing meaning of nature during the industrial revolution. He is, in fact, largely responsible for reviving the importance of landscape painting in the 19th century. A key event, when it is remembered that landscape would become the primary subject of the Impressionists later in the century.

Landscape had had a brief moment of glory amongst the Dutch masters of the 17th century. Ruisdael and others had devoted large canvases to the depiction of the low countries. But in the 18th century hierarchy of subject matter, landscape was nearly the lowest type of painting. Only the still-life was considered less important. This would change in the first decades of the 19th century when Constable began to depict his father’s farm on oversized six-foot long canvases. These “six-footers” as they are called, challenged the status quo. Here landscape was presented on the scale of history painting.

Why would Constable take such a bold step, and perhaps more to the point, why were his canvases celebrated (and they were, by no less important a figure than Eugène Delacroix, when Constable’s The Hay Wain was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1824)?

The Hay Wain does include an element of genre (the depiction of a common scene), that is the farm hand taking his horse and wagon (or wain) across the stream. But this action is minor and seems to offer the viewer the barest of pretenses for what is virtually a pure landscape. Unlike the later Impressionists, Constable’s large polished canvases were painted in his studio.

He did, however, sketch outside, directly before his subject. This was necessary for Constable as he sought a high degree of accuracy in many specifics. For instance, the wagon and tack (harness, etc.) are all clearly and specifically depicted, The trees are identifiable by species, and Constable was the first artist we know of who studied meteorology so that the clouds and the atmospheric conditions that he rendered were scientifically precise.

Constable was clearly the product of the Age of Enlightenment and its increasing confidence in science. But Constable was also deeply influenced by the social and economic impact of the industrial revolution.

Prior to the 19th century, even the largest European cities counted their populations only in the hundreds of thousands. These were mere towns by today’s standards. But this would change rapidly. The world’s economies had always been based largely on agriculture. Farming was a labour intensive enterprise and the result was that the vast majority of the population lived in rural communities. The industrial revolution would reverse this ancient pattern of population distribution. Industrial efficiencies meant widespread unemployment in the country and the great migration to the cities began. The cities of London, Manchester, Paris, and New York doubled and doubled again in the 19th century. Imagine the stresses on a modern day New York if we had even a modest increase in population and the stresses of the 19th century become clear.

Industrialization remade virtually every aspect of society. Based on the political, technological and scientific advances of the Age of Enlightenment, blessed with a bountiful supply of the inexpensive albeit filthy fuel, coal, and advances in metallurgy and steam power, the northwestern nations of Europe invented the world that we now know in the West. Urban culture, expectations of leisure, and middle class affluence in general all resulted from these changes. But the transition was brutal for the poor. Housing was miserable, unventilated and often dangerously hot in the summer. Unclean water spread disease rapidly and there was minimal health care. Corruption was high, pay was low and hours inhumane.

What effect did these changes have on the ways in which the countryside was understood? Can these changes be linked to Constable’s attention to the countryside? Some art historians have suggested that Constable was indeed responding to such shifts. As the cities and their problems grew, the urban elite, those that had grown rich from an industrial economy, began to look to the countryside not as a place so wretched with poverty that thousands were fleeing for an uncertain future in the city, but rather as an idealized vision.

The rural landscape became a lost Eden, a place of one’s childhood, where the good air and water, the open spaces and hard and honest work of farm labour created a moral open space that contrasted sharply with the perceived evils of modern urban life. Constable’s art then functions as an expression of the increasing importance of rural life, at least from the perspective of the wealthy urban elite for whom these canvases were intended. The Hay Wain is a celebration of a simpler time, a precious and moral place lost to the city dweller.

Excerpted and adapted from: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Constable and the English landscape,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/constable-and-the-english-landscape/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC:BY-NC-SA

Joseph Mallord William Turner in audio

Joseph Mallord William Turner

James Mallord William Turner was a child prodigy who had no idea he would develop into one of the premier Romantic Landscape painters of his time. At age 14 he was accepted into the Royal Academy by Sir Joshua Reynolds and by age 16 or 17 he was creating watercolour pieces like the one above. By the age of 21 he was exhibiting oil paintings, starting with Fisherman at Sea, with the Academy.

Turner was financially independent, although not due to family money as he was born into a staunchly lower-middle class family, and as an established artist he travelled extensively every year. Basically, he was the opposite of Constable, who was one year his junior. He was also very popular with the Academy because of his technical abilities and his ability to innovate. As with most who rise to fame based on innovation, his good name in the mainstream art world didn’t last forever. Starting out as highly talented artist meant that he also became a bit of an egotist and pushed his artistic innovations further than made his fellow Academy members (and the critics) comfortable. However, during his earlier years he found a name for himself as a painter of Seascapes. He also found good fortune in painting real-world events – contemporary history paintings of the sea.

Ambiguity was on Turner’s mind when he began work on his painting, whose full title is The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last berth to be broken up, 1838. He was familiar with the namesake ship, HMS Temeraire, as were all Britons of the day. Temeraire was the hero of the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, where Napoleon’s forces were defeated, and which secured British naval dominance for the next century.

By the late 1830s, however, Temeraire was no longer relevant. After retiring from service in 1812 she was converted into a hulk, a ship that can float but not actually sail. She spent time as a prison ship, housing ship, and storage depot before she was finally decommissioned in 1838 and sent up the River Thames to a shipyard in London to be broken into scrap materials. That trip on the Thames was witnessed by Turner, who used it as inspiration for his famous painting.

For many Britons, Temeraire was a powerful reminder of their nation’s long history of military success and a living connection to the heroes of the Napoleonic Wars. Its disassembly signaled the end of an historical era. Turner celebrates Temeraire’s heroic past, and he also depicts a technological change which had already begun to affect modern-day life in a more profound way than any battle.

Rather than placing Temeraire in the middle of his canvas, Turner paints the warship near the left edge of the canvas. He uses shades of white, grey, and brown for the boat, making it look almost like a ghost ship. The mighty warship is being pulled along by a tiny black tugboat, whose steam engine is more than strong enough to control its larger counterpart. Turner transforms the scene into an allegory about how the new steam power of the Industrial Revolution quickly replaced history and tradition.

Believe it or not, tugboats were so new that there wasn’t even a word for what the little ship was doing to Temeraire. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Turner’s title for his painting is the first ever recorded use of the word “tugged” to describe a steamship pulling another boat.

In addition to the inventive title, Turner included in the exhibition catalog the following lines of text, which he modified from a poem by Thomas Campbell’s “Ye Mariners of England”:

The flag which braved the battle and the breeze

No long owns herThis was literally true: Temeraire flies a white flag instead of the British flag, indicating it has been sold by the military to a private company. Furthermore, the poem acknowledges that the ship now has a different function. Temeraire used to be a warship, but no more.

In 1838 Temeraire was towed approximately 55 miles from its coastal dock to a London shipyard, and untold numbers of Britons would have witnessed the ship’s final journey. However, the Temeraire they saw only lightly resembled the mighty warship depicted by Turner. In reality her masts had already been removed, as had all other ornamentation and everything else of value on the ship’s exterior and interior. Only her barren shell was tugged to London.

Turner’s painting doesn’t show the reality of the event. He instead chose to depict Temeraire as she would have looked in the prime of her service, with all of its masts and rigging. This creates a dramatic juxtaposition between the warship and the tiny, black tugboat which controls its movements.

In fact there would have been two steamships moving Temeraire, but Turner exercised his artistic creativity to capture the emotional impact of the sight. Contemporary viewers recognized that The Fighting Temeraire depicts an ideal image of the ship, rather than reality.

Strong contrast is also visible in the way Turner applied paint to the various portions of his canvas. Temeraire is highly detailed. If you were to stand inches away from the painting, you would clearly see minuscule things like individual windows, hanging ropes, and decorative designs on the exterior of the ship. However, if you looked over to the sun and clouds you would see a heavy accumulation of paint clumped on the canvas, giving it a sense of chaos and spontaneity.

J. M. W. Turner part 2 in audio

Many works by Turner in this period of his life, like Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On) and Rain Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway (left), use the same effect, but The Fighting Temeraire stands out because of the naturalistic portrayal of the ship compared to the rest of the work.

Turner thought The Fighting Temeraire was one of his more important works. He never sold it, instead keeping it in his studio along with many of his other canvases. When he died in 1851 he bequeathed it and the rest of the paintings he owned to the nation. It quickly became seen as an image of Britain’s relationship to industrialization. Steam power has proved itself to be much stronger and more efficient than old technology, but that efficiency came with the cost of centuries of proud tradition.

Beyond its national importance, The Fighting Temeraire is also a personal reflection by the artist on his own career. Turner was 64 when he painted it. He’d been exhibiting at the Royal Academy of Arts since he was 15, and became a member at age 24, later taking a position as Professor of Painting. However, the year before he painted The Fighting Temeraire Turner resigned his professorship, and largely lived in secrecy and seclusion.

Although Turner remained one of the most famous artists in England until his death, by the late 1830s he may have thought he was being superseded by younger artists working in drastically different styles. He may have become nostalgic for the country he grew up in, compared to the one in which he then lived. Rain, Steam, and Speed – The Great Western Railway would reflect a similar interest in the changing British landscape several years later, focusing on the dynamic nature of technology. The Fighting Temeraire presents a mournful vision of what technology had replaced, for better or for worse.

Excerpted from: Dr. Abram Fox, “J. M. W. Turner, The Fighting Temeraire,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed September 20, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/turner-the-fighting-temeraire/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC:BY-NC-SA

By 1840, Turner’s innovations, which were not universally accepted as good workmanship by all, collided with the British Empire’s historical connections to slavery. Dredging up that shameful history, since slavery was now illegal in England, and combining it with Turner’s frenzied, brush-y style created an art-world scandal. And scandal and derision is not something Turner was used to. The young man who used to purposely delay finishing his paintings so he could put the finishing touches on them while they were being hung at a show (so he could hear the compliments and gather attention) was not in a position that was prepared for the newspapers ran biting, negative reviews about his work.

It would be unfair to judge the mainstream art world without establishing what they were expecting at the show. This piece, by Sir Edwin Landseer was the painting that took best in show in 1840 and it was the kind of lighthearted satire that viewers enjoyed. The dogs represent their various owners (or personalities) of the judicial system of London and while it may have been a slight jab at individuals in the legal profession, it was in no way a judgement of British culture as a whole. Unlike, Turner’s Slave Ship…

Throwing slaves overboard when a storm was coming was a common insurance fraud perpetrated by slave runners. Like other commodities and goods, slaves were insured against loss and damage by those that transported them. However, if they died of natural causes (like illness) during the journey, the insurance did not pay out. Therefore, it was common for slavers to see a storm coming and then throw overboard anyone who was ill, dying, or deceased and then claim them as lost at sea due to the storm. While this practice was no longer in practice by British ships (as slave running was now illegal), this was part of their cultural history. Lest viewers felt unprovoked by this image or were at a loss for its subject, Turner included an excerpt of an unfinished poem that he had written in 1812 titled Fallacies of Hope.

“Aloft all hands, strike the top-masts and belay;

You angry setting sun and fierce-edged clouds

Declare the Typhoon’s coming.

Before it sweeps your decks, throw overboard

The dead and dying- ne’er heed their chains

Hope, Hope, fallacious Hope!

Where is thy market now?”[46]

Ultimately, Turner was determined, as a British Romantic painter, to make landscape equal to history painting and raise its standing in the Academy. In his earlier works he incorporated elements of composition and atmosphere like those of the famous 17th and 18th century landscape painter Claude Lorrain. He added meaning and narrative in his landscapes. Yet, the logical progression of his innovative painting techniques and fascination with depicting light was for him to be drawn to the sublime power of nature.

John “Mad” Martin in audio

John “Mad” Martin

There’s a story that to paint Rain Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway Turner hung his head out of a train car window during a rainstorm to experience the speed. It’s highly likely that that story is more legend than fact, considering that during this time period it was quite common for most carriages in trains to have windows with no glass, so it wouldn’t really matter if your head was out the window or not you’d still be getting wet. But Turner had a contemporary that definitely did something like that.

John ‘Mad’ Martin

John Martin, always an inventor and engineer with a sense of adventure, stood on the front-end footplate of a train that was doing a test run to prove that trains could go faster than horses and achieve speeds of faster than 50 MPH (about 80 KPH). Born a few years after Constable and Turner (about eight years their junior), Martin is normally considered a Victorian painter with entertainment-level use of the Romantic Sublime. He, like Fuesli and West, painted huge paintings and lived off the sales of the print copies of those paintings. His paintings really were usually of epic proportions: think sizes of six feet by ten feet at any given time.

Martin’s nick name as John “Mad” Martin really didn’t have a lot to do with him or his mental state. It wasn’t really John who was mad, but his younger brother Jonathan (yes, a John and a Jonathan in the same family. Their parents were not all that inventive when it came to names, apparently). Jonathan suffered a few mental breakdowns and tried to burn down a church because the organ buzzed…although to tell the whole story, Jonathan had an ongoing dispute with that particular church’s minister regarding doctrinal understandings and after many letters and notes, Jonathan hid in the choir loft, removed all the bibles from the building, and set fire to the hymnals. Those kind of actions are easy to poke fun of once history has moved on, and make for amusing jokes at Jonathan’s expense but Jonathan is a classic example of a manic depressive or bi-polar arsonist. Unfortunately, for his brother John, Jonathan’s last public outburst would deplete John’s funds and set the artist on a path of financial ruin for a time. (Between the legal fees for his brother’s trial and the repeated lack of success with his engineering inventions – the pursuit he loved the most – Martin’s finances became quite strained at one point.)

Martin is one of these strange artists that don’t follow the rules of fine art as we know them. Usually, we think that artists are poor and unknown during their life and famous after death. Martin was the opposite. Famous and sought-out during his life, his work epitomized the Sublime. However, after his death the Sublime fell so far out of fashion that it became a source of ridicule and now he is largely forgotten by art history.

Sadak in Search of the Waters of Oblivion from 1812 was shown at the Academy. Martin painted the painting in a month and got really worried when he overheard the framer/hangers trying to figure out which end was up. However, despite his early concern, it went over well and sold at that very show.

Sadak was a fictional character from a pseudo-Orientalist story (completely made up by James Ridley and published in 1764) about a man sent on an impossible journey by a cruel Sultan to obtain the Waters of Oblivion, which make the drinker forget everything they knew. The Sultan wants to use this water on Sadak’s extremely beautiful wife so he can make her forget Sadak and seduce her for himself. (He feels it’s a win/win situation really. If Sadak dies on the perilous journey or if he obtains the water, either way the Sultan will still be able to obtain Sadak’s wife.) However, Sadak goes through his journey with trouble after trouble – this depiction of him here showing him just before he reaches the waters – and brings the water back. In the inevitable twist, the Sultan somehow ends up the victim of the water and Sadak becomes Sultan himself. (This story seems corny now, but the story was so popular at the time that it was made into a play and into an opera as well.)

The Last Judgement in audio

The Last Judgement

The three works that follow were meant to be seen as a triptych (a grouping of three paintings hung in a row) and they were his last paintings, finished two years before his death in 1854. Collectively they’re called The Last Judgement, but they have individual names as well. He started these paintings in 1849 or so, but it took him until 1852 to finish them.

The centre piece of the triptych is the first painting. The Last Judgement (the title of this single painting and the triptych as a whole) is an event related in the book of Revelations. During this event everyone on earth is judged by God and the Book of Life, shown on Christ’s lap in the centre background of the first painting, is searched for their name while the four and twenty elders watch from either side. If, during their lifetime on Earth, the individuals being judged have been found to believe that the death and resurrection of Christ was the sacrifice needed to redeem the debt and repair the separation from God caused by the wickedness that is innately in their being, their name will be found in the Lamb’s Book of Life.

Martin’s first painting in his depiction of this even shows he had distinct thoughts of who would and wouldn’t be found in the Lamb’s Book of Life, and included portraits of people he felt would definitely be there. Scholars are still identifying portraits of people from the left side of the painting – those who were welcome in the heavenly city in the mid-ground on the left.

However, if an individual’s name was not found in the Book of Life because they did not believe that Christ’s sacrifice was either enough, or real in any way, they would be damned and cast into the Lake of Fire. Those souls are portrayed on the right side of the painting and here you also find Martin’s personal thoughts on who would not be found in the Book. Interestingly, he didn’t think much of the Pope – fully believing that it wasn’t religion that would get people’s names into the Book but rather their personal beliefs. In the background there are trains falling off the abyss, labelled with the names a few of the major cities of Europe. (Elements of Martin’s post-apocalyptic judgement scenes have been recreated in many movies in the twentieth and twenty-first century due to their sublime use of epic emotion and horrifying symbolism.)

A continuation of the right side of the first painting, The Great Day of His Wrath shows the fate of those that did not find their names written in the Book of Life. Here Martin is illustrating another part of the same story in Revelation when the Sixth Seal is opened.

“…when he had opened the sixth seal, and lo, there was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became as blood;

And the stars of heaven fell unto the earth…

And the heaven departed as a scroll when it is rolled together; and every mountain and island were moved out of their places.

And the kings of the earth, and the great men and the rich men, and the chief captains, and the mighty men, and every bondman, and every free man, hid themselves in the dens and in the rocks of the mountains;

And said to the mountains and rocks, Fall on us, and hide us from the face of him that sitteth on the throne, and from the wrath of the Lamb:

For the great day of his wrath is come; and who shall be able to stand?”[47]

As you can see, he illustrated that cataclysmic destruction very well. Entire cities of people falling into the abyss, the mountains crumbling, and the sublime pyroclastic sky complete with the lightning that can be caused by intense volcanic activity. Very much in the sublime tradition but with all the stops, guards, and safeties removed.

But the Sublime horror and apocalyptic terror in his depiction of the damned melts away into Picturesque calm in a depiction of the redeemed in the final painting of the triptych, The Plains of Heaven.

The last picture of the triptych was meant to be hung on the left side, showing the plains of Heaven. Some say what Martin painted here was related to his memory of his childhood in Allendale, as well as based on sketched by Turner, and also related to some of his own earlier, personal landscape sketches. Regardless of its aesthetic influences, it also follows very closely what the book of Revelation relates.

The river flows into the painting from the right, clear as crystal, and issuing from the throne of God that is depicted in the middle piece of the triptych. It pools in the centre – the Water of Life. The shrubby tree in the foreground would be the Tree of Life bears a variety of fruit and flowers. In the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the ground was cursed because of their sin and forever laboured to produce life, but here there is no curse on the land. Everything is clean, pure and growing well. In Heaven there no night, so notice the source of light in this painting is coming from the painting beside it- glowing from the Throne of God.

About a year after these paintings were finished Martin had a massive stroke and died a year later. However, during that time these paintings went on a colossal tour and it’s said that over eight million people saw these during that tour.

The drama felt in Martin’s The Great Day of His Wrath, is partly the reason his work fell out of fashion after his death. It was considered too theatrical and too emotional to be respected, as a new age of Realism was ushered in.

Self-Reflection Question 4.2

Reflect on the following:

- Landscape painting in Britain has a long history – from relaying ownership, to depicting perfection, to narrating stories, to changing how the landscape (in paintings and in life) was thought about.

Considering your own experiences, do you think the landscape has as much importance or influence now?

- Oxford Lexico, (2020), s.v. "Sublime." ↵

- Merriam-Webster, (2020), s.v. "Sublime." ↵

- Webster's Dictionary, (1828), s.v. "Sublime." ↵

- Wikipedia, (July 5, 2020), s.v. "Sublime (philosophy)." ↵

- Wikipedia, (June 22, 2020), s.v. "Sublime (literary)." ↵

- Wikipedia, (June 22, 2020), s.v. "Sublime (literary)." ↵

- Allen Staley, "West's "Death on the Pale Horse"," Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts,. 58, no. 3 (1980): 141-142. ↵

- Staley, "West's," 142. ↵

- Staley, "West's," 142. ↵

- Kenneth Clark, The Romantic Rebellion: Romantic versus Classic Art, (London, UK: Futura Publications Limited, 1973) 45. ↵

- Clark, Nightmare, 45. ↵

- Clark, Nightmare, 45. ↵

- Frederick Antal, Fuseli Studies, (London, UK: Routledge, 1956), 93. ↵

- Nicolas Powell, Fuseli: The Nightmare, (New York, NY: Viking Press, 1972),49. ↵

- Peter Tomory, The Life and Art of Henry Fuseli, (London, UK: Thames & Hudson, 1972), 182. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 75. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 49. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 49. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 48. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 49. ↵

- Anne K. Metter,Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters, (New York: Routledge, 1989), 243. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 60. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 60. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 60. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 60. ↵

- Metter, Mary Shelley, 243. ↵

- Jack Tresidder, The Complete Dictionary of Symbols in Myth, Art and Literature, (London: Duncan Baird Publishers, 2004), 242. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 56. ↵

- Tresidder, Complete Dictionary, 241. ↵

- Tomory, Life, 125. ↵

- Tomory, Life, 125. ↵

- Tomory, Life, 125. ↵

- Tomory, Life, 125. ↵

- Henry Fuseli, "Aphorisms on Art," in Art in Theory, 1648-1815: An Anthology of Changing ldeas, eds. Charles Harison, Paul Wood and Jason Gaiger, (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2000), 952. ↵

- Fuseli, Aphorisms, 952. ↵

- Tresidder, Complete Dictionary, 409. ↵

- Metter, Mary Shelley, 121. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 75. ↵

- Metter, Mary Shelley, 121. ↵

- Andrew Webber, The Doppelganger: Double Visions in German Literature, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 240. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 64. ↵

- Powell, Fuseli, 64. ↵

- J. Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993), n.p.; M. Phillips, William Blake: The Creation of the Songs, (London: The British Library, 2000), n.p. ↵

- Jane Webb Loudon, The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century, (Project Gutenberg, 1827), n.p. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/56426/56426-h/56426-h.htm[ ↵

- Dr. Leslie Dawn, "The Group of Seven and Tom Thompson", (lecture, ARTH 3151: Canadian Art History, Lethbridge, AB, 2006). ↵

- A. J. Finberg, "The Life of J.M.W. Turner," (R.A., 1961), 474. ↵

- Revelations 6: 12-17 KJV ↵