6 Chapter 5 – Romanticism in Spain and Germany

Spain & Germany

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- Identify the works of Francisco Goya

- Explain Goya’s general philosophical and/or political motivations for his work

- Outline the basic beliefs of the German Nazarenes and explain how they relate to Germanic Romanticism

- Explain the importance of Philipp Otto Runge’s relationship to landscape painting & colour theory

- Define the art term Rückenfigur and who invented the compositional device

Audio recording of chapter opening:

Audio recording of the full chapter can be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1cFfnJ5-Iy-kXdGezJSf9TCwpqV9caI4N/view?usp=sharing

A Home Invasion is when people come into a home to steal property, but also have the intent to damage the property and/or perpetrate violence against the home occupants. In many cases the home invader breaks into the dwelling through force, but sometimes they can gain access through false pretenses and therefore can, initially, be there by the invitation and welcome of the home owner.

But what is it called when the home invaders have the intent to steal, not just items from inside the property, but they intend to steal the property itself from the rightful dwellers?

This is the case with Napoleon and Spain.

Napoleon was in a scuffle with Portugal and asked his ally, the King of Spain, if he could gain access to Portugal by moving his military through Spain. The King of Spain agreed and Napoleon used the pretext of bulking up military presence in Portugal and giving aid to the Spanish army as an ally to take control of the Spanish throne and put his brother – Joseph-Napoléon Bonaparte – on the throne. The royal family of Spain, much like the royal family of Portugal, quietly vacated the premises in the face of Napoleon’s force and King Joseph I took the throne.

Napoleon felt that there were those in the Spanish royal court who were a little too anti-French and too pro-British for his comfort; so to ensure Spanish support in his planned maneuvers against Portugal (Britain’s ally) and Britain, he took control of Spain. What may have seemed to Napoleon back in France as one part liberation of the Spanish people from their tired monarchy and three parts a guaranteed political union between Spain and France against Britain was not necessarily how the people of Spain saw it. The removal of the royal family caused unexpected uprisings among the people because as much as the monarchy was tired and corrupt and generally just not the best, they were beloved by their subjects in the kind of way that saw the citizens of Spain not welcoming the French troops and rule.

On May 2nd, 1808 the people of Madrid rose up and resisted the elite French Imperial Guard – depicted in Francisco Goya’s painting as the historical enemy of the Spanish people, the Moors. The citizens of Madrid had gathered to protest the change in government and the removal of their royal family and the French Imperial Guard were ordered to disperse an angry, rioting, crowd by charging the people. Instead of running the people stood their ground and fought back and bloody skirmish resulted.

And that was the beginning of the Dos de Mayos uprisings.

The results, besides a long and gruesome war that created a brand new kind of warfare and caused death and suffering to innumerable people, where law changes. Such as: anyone who was found with a weapon would be punished by death. We will see the result of that ruling in a little while.

Audio recording of Francisco Goya segment:

Francisco Goya

In Spain, there was one major job for artists – court painter – many of the famous painters from Spain in art history were court painters and this is, in part, because art and the art world in Spain was different than anywhere else in Europe. This can be traced to the impact of the Spanish Inquisition on Spanish life and culture. I always thought that the Spanish Inquisition was a thing of the medieval days and Edgar Allan Poe spine-tinglers. (Incidentally, Poe’s Inquisition-inspired The Pit and the Pendulum is set in the same time period as we are about to discuss, but be warned – it’s terrifying.) And while the Spanish Inquisition was most active during the 1300 and 1400s they definitely saw a resurgence of power after Napoleon’s reign in Spain. Interestingly, the Spanish Inquisition – or Holy Office as it was called officially – took issue with those who fought against the Napoleonic claim to the throne. Even though the Holy Office was abolished under Napoleon (remember the mind games with the Catholic Church at Napoleon’s coronation?). It is possible that as the Inquisition was losing power under the monarchy in Spain and saw Napoleon as an opportunity; by the late 1700s the Holy Office was simply a censorship body and only prosecuted the rich who were deemed ‘not Roman Catholic enough.’ The Holy Office would also have been terrified of the ideals of the Enlightenment that had been creeping into Spain, despite their best efforts to censor. It is logical that they could have thought that Napoleon – a good Catholic emperor – would reinstitute their waning power. He didn’t. They were disbanded and only brought together again once the Bourbon monarchy had been re-established. (And then disbanded completely and forever after that monarchy failed).

Now, I say all that to talk about Francisco Goya. In 1815 Goya was brought before the Inquisition to answer for this set of paintings – which they had confiscated. The artistic nude was considered unacceptable to the Church before the Peninsular Wars, so after they were over Goya had to answer for this picture – specifically the one the right. He was asked repeatedly who his model was; not so much because the act of modeling nude was more punishable than the act of painting a nude, but because of who the model was suspected to be. There was a saying late in the Inquisition, “Only the rich burn,” meaning that the Holy Office would only target and fully prosecute those who had property and possessions that could be forfeited to the Roman Catholic Church. It was rumoured that the model was the Duchess of Alba – and if it was, she was rich and would be a source of good money if they could confiscate her holdings on account of un-moral, heretical behaviour. In this painting of Duchess of Alba, called The Black Duchess is pointing to an inscription in the sand that says Only Goya – which may be a reference to a bit of a crush she had on Goya (and maybe Goya on her) after the death of her husband. However, it may also simply be a device to refer to his signature, as the other painting in the Duchess series, The White Duchess, also shows her pointing to his signature.

But back to the Maja paintings. The first one took three years to paint, the second took five. They were returned, after being confiscated, to the San Fernando Academy of Fine Arts in the late 1830s. One hundred years later, in the 1930s, Spain issued stamps with Goya’s Majas on them. This was the first time a nude woman was on a stamp and the U.S. Mail system didn’t really know what to do with that. The U.S. postal system refused to accept any incoming mail with the nude stamp (the clothed edition was fine) and returned to Spain all the mail with the Maja Desnuda on it.

While Goya was never actually put on trial for this painting and there isn’t any record that he ever said who the model was or why he painted the picture, being called before the Inquisition caused him to lose the practical applications of his position as court painter. He kept his salary and his title, but was forced to move to the country. He bought Quinta del Sordo (the house of the deaf man) – called such because the previous owner had suffered an illness that had left him deaf. However, Goya was also in a state of decreasing health and bouts with an undiagnosed illness had left him with vertigo, tinnitus and deafness, so the name of his new house seemed to be a fitting choice.

All the paintings he did after he moved to Quinta del Sordo in 1913 were either for himself or for his friends, however while he had been in the court of the King of Spain he had created a number of works that are still well known today.

This painting of the royal family inserts the artist into the painting in the background on the left, and it is just as confusing as Velazquez’s Las Meninas from the 1600s that influenced it. In Valzquez’s painting, it shows the scene as if the painter is painting the viewer who is standing with their back to the king and queen (which was a punishable offence – standing with one’s back to the monarchy). In both paintings it is a strange vantage point for the viewer because of the presence of the artist. Goya idolized Velazquez and perfected Velazquez’s strange viewer placements.

Even just taking a quick look at the painting of the family of King Charles IV, it is plain to see that Goya didn’t sanitize or idealize the looks of the royal family. Huge birthmark here, bulging eyes there. And strangely enough while some of these figure are firmly cemented in the portrait, some, like the two princes on the left, seem like they are pasted overtop. Obviously, it wasn’t that Goya couldn’t control his lighting and this was a mistake, Goya was making stylistic choices.

Also. Notice the fifth figure in from the left – the woman looking away from the viewer. This was not a comment on the intelligence or beauty of that member of the royal family, but rather an artistic choice common in royal portraits at the time. The prince – Fernando VII – was not betrothed when the painting was painted. So, it was asked that Goya would paint in his future wife and the tradition was that the face would be obscured because, obviously, he would have a wife eventually, they just didn’t know what face she’d have.

Look at the King and Queen in the center. They are not idealized in the Rococo fashion, but ‘realistic’ or honest – as the case may be. Some say that Goya was poking fun at the royal family and they were too stupid to realize, but others think this was a calculated move on the royal family’s part – by showing their riches and their faults they were showing they were honest and open and self-aware. Not hiding in frippery. Although, of course they weren’t actually being completely honest or open or self-aware. The king was terribly manipulated by his wife who slept with the Prime Minister and the crowned prince bossed the king around, too. But that probably was more honesty than they wanted to share with the public…

And Goya wasn’t unkind for the sake of being unkind. Some of the people in this painting look just fine. Not idealized in the Rococo way, but quite unblemished. The grouping of the three on the right is the duke of Parma – Don Luis de Parma, his wife, and baby Carlos Luis, the future Duke of Parma and they are painted quite pleasantly. One last thing to looks for: notice how the head floating behind the king looks so much like the king? That’s his brother.

Audio recording of Los Caprichos segment:

Often this painting is considered a kind of satire or mockery of the royal family. But this projects a different cultural lens on things than was a reality in Spain. Because of the Spanish Inquisition there wasn’t a lot of room for satire or humour in art; anything too offensive would have drawn the attention of the Holy Office. As well, the Spanish people were not French – they did not dispose of their king after decades of publicly making fun of the royal family and satirizing their roles, personalities, or looks. In Spain there was obviously laughter and fun, but it did not frequently appear in art of the court, directed at the court. And on the occasion that satire did appear, if it was not carefully executed, it caused the artist to be called before the Holy Office. Goya’s Los Caprichos series did both.

The Los Caprichos series, as the title suggests was one of invention and fantasy. Goya’s use of the term is a nod to the followers of this tradition: Botticelli and Dürer and the later Tiepolo and Piranesi. It denoted the promotion of the artist’s imagination over reality; invention over mere representation. However, Goya uses this trope in a very new way. Where previous caprices had been fantastic and escapist, Goya’s Los Caprichos were different, as David Rosand points out: “Goya turned the inventive powers of the artist back upon his audience with indicting moral force. Pressing the limits of poetic license, he effectively annulled the contract between artist and society that had sustained the development of the capriccio.”. Whereas today many people are perfectly happy to believe or accept that art can exist for art’s sake, arguably, Goya believed that art should ultimately make a difference. He uses his position as illustrado to lampoon, satirize and pillory various institutions, practices and commonly held beliefs.[1]

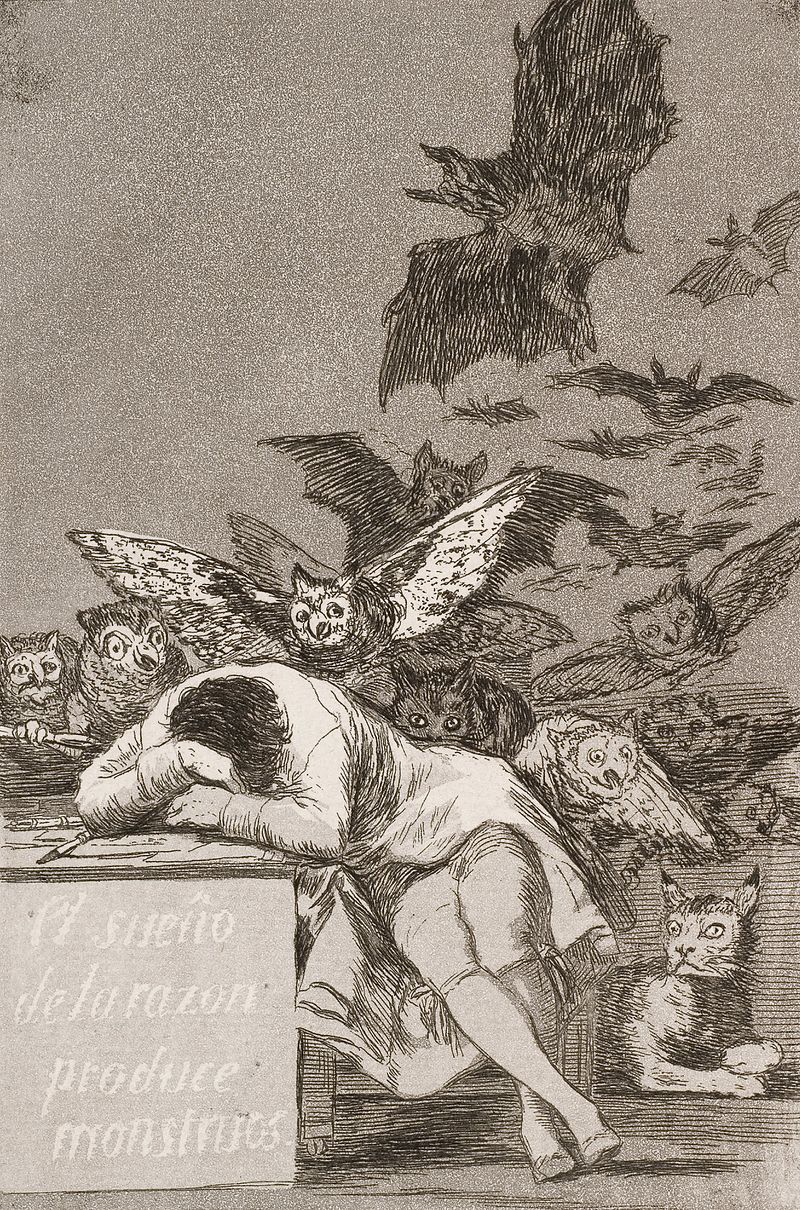

The front plate of Goya’s Los Caprichos series was The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. In this print a man sleeps, apparently peacefully, even as bats and owls threaten from all sides and a lynx lays quiet, but wide-eyed and alert. Another creature sits at the center of the composition, staring not at the sleeping figure, but at us. Goya forces the viewer to become an active participant in the image––the monsters of his dreams even threaten us.

On 6 February 1799, Francisco Goya put an advertisement in the Diario de Madrid. “A Collection of Prints of Capricious Subjects,” he tells the reader, “Invented and Etched by Don Francisco Goya,” is available through subscription. We know this series of eighty prints as Los Caprichos (caprices, or follies).

Los Caprichos was a significant departure from the subjects that had occupied Goya up to that point––tapestry cartoons for the Spanish royal residences, portraits of monarchs and aristocrats, and a few commissions for church ceilings and altars.

Many of the prints in the Caprichos series express disdain for the pre-Enlightenment practices still popular in Spain at the end of the Eighteenth century (a powerful clergy, arranged marriages, superstition, etc.). Goya uses the series to critique contemporary Spanish society. As he explained in the advertisement, he chose subjects “from the multitude of follies and blunders common in every civil society, as well as from the vulgar prejudices and lies authorized by custom, ignorance or interest, those that he has thought most suitable matter for ridicule.”

The Caprichos was Goya’s most biting critique to date, and would eventually be censored. Of the eighty aquatints, number 43, “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,” can essentially be seen as Goya’s manifesto and it should be noted that many observers believe he intended it as a self-portrait.

In the image, an artist, asleep at his drawing table, is besieged by creatures associated in Spanish folk tradition with mystery and evil. The title of the print, emblazoned on the front of the desk, is often read as a proclamation of Goya’s adherence to the values of the Enlightenment—without Reason, evil and corruption prevail.

However, Goya wrote a caption for the print that complicates its message, “Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters; united with her, she is the mother of the arts and source of their wonders.” To make things even more complicated, his inscription meant to accompany the entire Los Caprichos etching series reads, “The artist dreaming. His only purpose is to banish harmful, vulgar beliefs and to perpetuate in this work of caprices the solid testimony of truth”.

In other words, Goya believed that imagination should never be completely renounced in favor of the strictly rational. For Goya, art is the child of reason in combination with imagination.

Audio recording of the beginnings of romanticism in Spain:

The beginnings of Romanticism in Spain

With this print, Goya is revealed as a transitional figure between the end of the Enlightenment and the emergence of Romanticism. The artist had spent the early part of his career working in the court of King Carlos III who adhered to many of the principles of the Enlightenment that were then spreading across Europe––social reform, the advancement of knowledge and science, and the creation of secular states. In Spain, Carlos reduced the power of the clergy and established strong support for the arts and sciences.

However, by the time Goya published the Caprichos, the promise of the Enlightenment had dimmed. Carlos III was dead and his less respected brother assumed the throne. Even in France, the political revolution inspired by the Enlightenment had devolved into violence during an episode known as the Reign of Terror. Soon after, Napoleon became Emperor of France.

Goya’s caption for “The Sleep of Reason,” warns that we should not be governed by reason alone—an idea central to Romanticism’s reaction against Enlightenment doctrine. Romantic artists and writers valued nature which was closely associated with emotion and imagination in opposition to the rationalism of Enlightenment philosophy. But “The Sleep of Reason” also anticipates the dark and haunting art Goya later created in reaction to the atrocities he witnessed—and carried out by the standard-bearers of the Enlightenment—the Napoleonic Guard.

Goya brilliantly exploited the atmospheric quality of aquatint to create this fantastical image. This printing process creates the grainy, dream-like tonality visible in the background of “The Sleep of Reason.”

Although the aquatint process was invented in 17th century by the Dutch printmaker, Jan van de Velde, many consider the Caprichos to be the first prints to fully exploit this process.

Aquatint is a variation of etching. Like etching, it uses a metal plate (often copper or zinc) that is covered with a waxy, acid-resistant resin. The artist draws an image directly into the resin with a needle so that the wax is removed exposing the metal plate below. When the scratch drawing is complete, the plate is submerged in an acid bath. The acid eats into the metal where lines have been etched. When the acid has bitten deeply enough, the plate is removed, rinsed and heated so that the remaining resin can be wiped away.

Aquatint requires an additional process, the artist sprinkles layers of powdery resin on the surface of the plate, heats it to harden the powder and dips it in an acid bath.

The acid eats around the resin powder creating a rich and varied surface. Ink is then pressed into the pits and linear recesses created by the acid and the flat surface of the plate is once again wiped clean. Finally, a piece of paper is pressed firmly against the inked plate and then pulled away, resulting in the finished image.

Excerpted and adapted from: Sarah C. Schaefer, “Francisco Goya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/goya-the-sleep-of-reason-produces-monsters/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

Audio recording of May 2, 1808 segment:

On May 2, 1808, hundreds of Spaniards rebelled. On May 3, these Spanish freedom fighters were rounded up and massacred by the French for crimes as serious as attacking the French Imperial Guard and for crimes as petty as having a weapon in their possession. Their blood literally ran through the streets of Madrid. Even though Goya had shown French sympathies in the past, the slaughter of his countrymen and the horrors of war made a profound impression on the artist. He commemorated both days of this gruesome uprising in paintings. Although Goya’s Second of May, 1808 (at the beginning of this chapter) is a tour de force of twisting bodies and charging horses reminiscent of Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari, his The Third of May, 1808 in Madrid is acclaimed as one of the great paintings of all time, and has even been called the world’s first modern painting.

We see row of French soldiers aiming their guns at a Spanish man, who stretches out his arms in submission both to the men and to his fate. A country hill behind him takes the place of an executioner’s wall. A pile of dead bodies lies at his feet, streaming blood. To his other side, a line of Spanish rebels stretches endlessly into the landscape. They cover their eyes to avoid watching the death that they know awaits them. The city and civilization is far behind them. Even a monk, bowed in prayer, will soon be among the dead.

Goya’s painting has been lauded for its brilliant transformation of Christian iconography and its poignant portrayal of man’s inhumanity to man. The central figure of the painting, who is clearly a poor laborer, takes the place of the crucified Christ; he is sacrificing himself for the good of his nation. The lantern that sits between him and the firing squad is the only source of light in the painting, and dazzlingly illuminates his body, bathing him in what can be perceived as spiritual light. His expressive face, which shows an emotion of anguish that is more sad than terrified, echoes Christ’s prayer on the cross, “Forgive them Father, they know not what they do.” Close inspection of the victim’s right hand also shows stigmata, referencing the marks made on Christ’s body during the Crucifixion.

The man’s pose not only equates him with Christ, but also acts as an assertion of his humanity. The French soldiers, by contrast, become mechanical or insect-like. They merge into one faceless, many-legged creature incapable of feeling human emotion. Nothing is going to stop them from murdering this man. The deep recession into space seems to imply that this type of brutality will never end.

This depiction of warfare was a drastic departure from convention. In 18th century art, battle and death was represented as a bloodless affair with little emotional impact. Even the great French Romanticists were more concerned with producing a beautiful canvas in the tradition of history paintings, showing the hero in the heroic act, than with creating emotional impact. Goya’s painting, by contrast, presents us with an anti-hero, imbued with true pathos that had not been seen since, perhaps, the ancient Roman sculpture of The Dying Gaul. Goya’s central figure is not perishing heroically in battle, but rather being killed on the side of the road like an animal. Both the landscape and the dress of the men are nondescript, making the painting timeless. This is certainly why the work remains emotionally charged today.

Adapted and excerpted from: Christine Zappella, “Francisco Goya, The Third of May, 1808,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed October 2, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/goya-third-of-may-1808/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

Audio Recording of The Disasters of War segment:

The Disasters of War Series, 1810-1820. 82 plates.

Content warning: disturbing imagery and themes of violence and death

Goya never said why he created the Disasters of War, but it is generally accepted that he made them to protest the Peninsular War and other uprisings during that time period. The only thing that is known that he said about these was his original title – which wasn’t the Disasters of War (or Horrors of War as it is sometimes called). It was, translated: Fatal consequences of Spain’s bloody war with Bonaparte, and other emphatic caprices – which may show that he considered them another chapter of his Caprichos series. The series shows the brutal things that humans can do to other humans, but they are not accompanied with much (or any) written artists statement of intent.

In the piece above, For a Clasp Knife a clergyman is shown tied to a pole by his neck and on his chest is pinned the account of his crime – possession of a knife. The knife is strung around his neck and is a common clasp knife. However, it was illegal for citizens to possess weapons and what was likely use to cut food and pull slivers, was now considered a weapon of war and the repercussions were horrible.

Francisco Goya created the aquatint series The Disasters of War from 1810 to 1820. The eighty-two images add up to a visual indictment of and protest against the French occupation of Spain by Napoleon Bonaparte. The French Emperor had seized control of the country in 1807 after he tricked the king of Spain, Charles IV, into allowing Napoleon’s troops to pass its border, under the pretext of helping Charles invade Portugal. He did not. Instead, he usurped the throne and installed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as ruler of Spain. Soon, a bloody uprising occurred, in which countless Spaniards were slaughtered in Spain’s cities and countryside. Although Spain eventually expelled the French in 1814 following the Peninsular War (1807-1814), the military conflict was a long and gruesome ordeal for both nations. Throughout the entire time, Goya worked as a court artist for Joseph Bonaparte, though he would later deny any involvement with the French “intruder king.”

The first group of prints, to which There is Nothing to Be Done belongs, shows the sobering consequences of conflict between French troops and Spanish civilians. The second group, of which Cartloads for the Cemetery is part, documents the effects of a famine that hit Spain in 1811-1812, at the end of French rule. The final set of pictures depicts the disappointment and demoralization of the Spanish rebels, who, after finally defeating the French, found that their reinstated monarchy would not accept any political reforms. Although they had expelled Bonaparte, the throne of Spain was still occupied by a tyrant. And this time, they had fought to put him there.

Although There’s Nothing to Be Done may have crystallized the theme of The Disasters of War, it is not the most gruesome. This honor may belong to the print Esto es peor (This is Worse), which captures the real-life massacre of Spanish civilians by the French army in 1808. In the macabre image, Goya copied a famous Hellenistic Greek fragment, the Belvedere Torso, to create the body of the dead victim. Like the ancient fragment, he is armless, but this is because the French have mutilated his body, which is impaled on a tree. As in There is Nothing to be Done, the corpse face stares out at the viewer, who must confront his own culpability in allowing the massacre to take place. There is Nothing to be Done, can also be compared to the plate No se puede mirar (One cannot look), in which the same faceless line of executioners points their weapons at a group of women and men, who are about to die.

The Disasters of War were Goya’s second series, made after his earlier Los Caprichos. This set of images was also a critique of the contemporary world in Spain that caused most people to live in poverty and forced them to act immorally just to survive. Goya condemned all levels of society, from prostitutes to clergy. But The Disasters of War was not the last time that Goya would take on the subject of the horrors of the Peninsular War. In 1814, after completing The Disasters of War, Goya created his masterpiece The Third of May, 1808 which portrays the ramifications of the initial uprising of Spanish against the French, right after Napoleon’s takeover. Sometimes called “The first modern painting,” its resemblance to There is Nothing to Be Done is undeniable. In this painting, a Christ-like figure stands in front of a firing squad, waiting to die. This line of soldiers is nearly identical to the murderers in the aquatint. In The Third of May, 1808 the number of assassins and victims is countless, indicating, once again, that “there is nothing to be done.” Although it is impossible to say whether the print or the painting came first, the repetition of the imagery is evidence that this theme—the inexorable cruelty of one group of people towards another—was a preoccupation of the artist, whose imagery would only become darker as he became older.

Goya’s Disasters of War series was not printed until thirty-five years after the artist’s death, when it was finally safe for the artist’s political views to be known. The images remain shocking today, and even influenced the novel of famous American author Ernest Hemingway, For Whom the Bell Tolls, a book about the violence and inhumanity in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Hemingway shared Goya’s belief, expressed in The Disasters of War, that war, even if justified, brings out the inhumane in man, and causes us to act like beasts. And for both artists, the consumer, who examines the dismembered corpses of the aquatints or reads the gruesome descriptions of murder but does nothing to stop the assassin, is complicit in the violence with the murderer.

Audio recording of The Artist’s Process segment:

The Artist’s Process

Goya created his Disasters of War series by using the techniques of etching and drypoint. Goya was able to use this technique to create nuanced shades of light and dark that capture the powerful emotional intensity of the horrific scenes in the Disasters of War.

The first step was to etch the plate. This was done by covering a copper plate with wax and then scratching lines into the wax with a stylus (a sharp needle-like implement), which thus exposed the metal. The plate was then placed in an acid bath. The acid bit into the metal where it was exposed (the rest of the plate was protected by the wax). Next the acid was washed from the plate and the plate was heated so the wax softened and could be wiped away. The plate then had soft, even, recessed lines etched by the acid where Goya had drawn into the wax.

The next step, drypoint, created lines by a different method. Here Goya scratched directly into the surface of the plate with a stylus. This resulted in a less even line since each scratch left a small ragged ridge on either side of the line. These minute ridges catch the ink and create a soft distinctive line when printed. However, because these ridges are delicate and are crushed by repeatedly being run through a press, the earliest prints in a series are generally more highly valued.

Finally, the artist inked the plate and wiped away any excess so that ink remained only in the areas where the acid bit into the metal plate or where the stylus had scratched the surface. The plate and moist paper were then placed atop one another and run through a press. The paper, now a print, drew the ink from the metal, and became a mirror of the plate.

Adapted and excerpted from: Christine Zappella, “Francisco Goya, And there’s nothing to be done from The Disasters of War,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/goya-and-theres-nothing-to-be-done-from-the-disasters-of-war/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

The last group of paintings that have been attributed to Goya are called the Black Paintings. Found on the walls of his home, they were gruesome and dark in technique and theme.

The reasons for these paintings were never explained by Goya. (I think by now you can see that he wasn’t the biggest talker.) He didn’t often explain his art – probably partly because of the era he lived in. It’s likely that artists didn’t want to write down something that could then be used as evidence of sedition or treason.

The Black Paintings were painted directly on the plaster of his house and were later removed from the wall and mounted on canvas for their move to the museum that purchased them (this happened many years after Goya’s death. The paintings depict wildly disturbing scenes that were never meant to be seen by strangers. They represent Goya’s own thoughts and statements for himself and all were titled after his death (if he gave them titles, they have been lost with him) and therefore the titles do not faithfully represent what Goya meant to communicate with the works.

While Saturn Devouring His Son may be the most popularly known piece from Goya’s Black Paintings, his painting The Dog – depiction of what is commonly thought to be a drowning dog – has had the biggest impact on artists who followed after him because of his use of colour gradients and implied themes (but mostly the colour gradients).

There is, of course, a major debate regarding Goya’s Black Paintings. Most scholars firmly believe that Goya’s son and grandson told the truth and that the famous artist painted these paintings while living at Quinta del Sordo. But there are some who feel this may be one of the art world’s most successful con jobs.

The problem with the Black Paintings is this: there is actually no evidence that Goya painted them.

So first the lack of evidence: no visitor ever mentioned them. Ever. And when you think about living in the early 1800s and giving Goya a visit and that painting of Saturn is hanging around as you sip your coffee and talk about the weather, you’d probably mention them to someone after you left the Goya residence. Probably. (I mean, I would. Hey, I wasn’t even in the Goya house and I’m telling out about them!)

Then there’s the reputed character of Goya’s offspring: the sad fact is that his son was the kind of businessman that would have sold his own mother and that his grandson was a down-on-his-luck type.[2]

Then there is the work of art historian Juan José Junquera. While his work is disputed by other Goya scholars, Junquera lays the groundwork of a convincing argument. Junquera claims that according to land deeds at the time of purchase Quintas del Sordo was a single story home when Goya bought it.[3] He also found that there was no permit for an expansion to add a second floor until after Goya’s death.[4] These home repair and renovation facts don’t seem all that interesting until we realize half of the paintings were found on the second floor walls.[5]

These findings make some people think that the paintings were painted by his son and sold either by his son or by his grandson for the money his famous name would give.

When asked if museums would remove the Black Paintings or re-attribute the work in face of the evidence Junquera discovered, museum curators said they would not because paintings like The Dog had been too influential to artists in the 1900s to be changed in their standing.[6] And while it might seem a bit like the museum curators are playing a little more freely with the facts than one would expect, this is not an uncommon stance in museum culture. There are many famous pieces of art that are seen by contemporary viewers in ways that were never meant by the artist. Rembrandt’s The Nightwatch was neither called “The Nightwatch” nor was it a night scene when the artist first completed it, but years of grime darkened the painting and the scene became recognized as a night view of military maneuvers. When it was suggested that the piece be cleaned (which it finally was in 2019), many suggested it be left as it was as the darkened state was how it was recognized.

For some art is not firmly rooted in the realm of facts and truth, but rather in aesthetics and perceptions.

But returning to the Black Paintings. Are these the cleverest forgeries ever? Or are they really Goya’s work? Lots of people say they know one way or the other, but what stands is that they are exceptional paintings that have influenced the path of modern art.

Self-Reflection Question 5.1

- Goya wrote that the artist’s “…only purpose is to banish harmful, vulgar beliefs and to perpetuate…the solid testimony of truth.” Do you feel this is true or do you feel there are other goals artists should have? Why do you feel that way?

Audio recording of German Romanticism segment:

German Romanticism

Compared to English Romanticism, German Romanticism developed relatively late, and, in the early years, coincided with Weimar Classicism (1772–1805). In contrast to the seriousness of English Romanticism, the German variety of Romanticism notably valued wit, humor, and beauty.

Romanticism was also inspired by the German Sturm und Drang movement (Storm and Stress), which prized intuition and emotion over Enlightenment rationalism. This proto-romantic movement was centered on literature and music, but also influenced the visual arts. The movement emphasized individual subjectivity. Extremes of emotion were given free expression in reaction to the perceived constraints of rationalism imposed by the Enlightenment and associated aesthetic movements.

Sturm und Drang in the visual arts can be witnessed in paintings of storms and shipwrecks showing the terror and irrational destruction wrought by nature. These pre-romantic works were fashionable in Germany from the 1760s on through the 1780s, illustrating a public audience for emotionally charged artwork. Additionally, disturbing visions and portrayals of nightmares were gaining an audience in Germany as evidenced by Goethe’s possession and admiration of paintings by Fuseli, which were said to be capable of “giving the viewer a good fright.”

The early German Romantics strove to create a new synthesis of art, philosophy, and science, largely by viewing the Middle Ages as a simpler period of integrated culture, however, the German romantics became aware of the tenuousness of the cultural unity they sought. Late-stage German Romanticism emphasized the tension between the daily world and the irrational and supernatural projections of creative genius. Key painters in the German Romantic tradition include Joseph Anton Koch, Adrian Ludwig Richter, Otto Reinhold Jacobi, and Philipp Otto Runge among others.

Excerpted and Adapted from: Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-arthistory/chapter/neoclassicism-and-romanticism/

License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Philipp Otto Runge

Philipp Otto Runge was of a mystical, deeply Christian turn of mind, and in his artistic work he tried to express notions of the harmony of the universe through symbolism of colour, form, and numbers. He considered blue, yellow, and red to be symbolic of the Christian trinity and equated blue with God and the night, red with morning, evening, and Jesus, and yellow with the Holy Spirit.

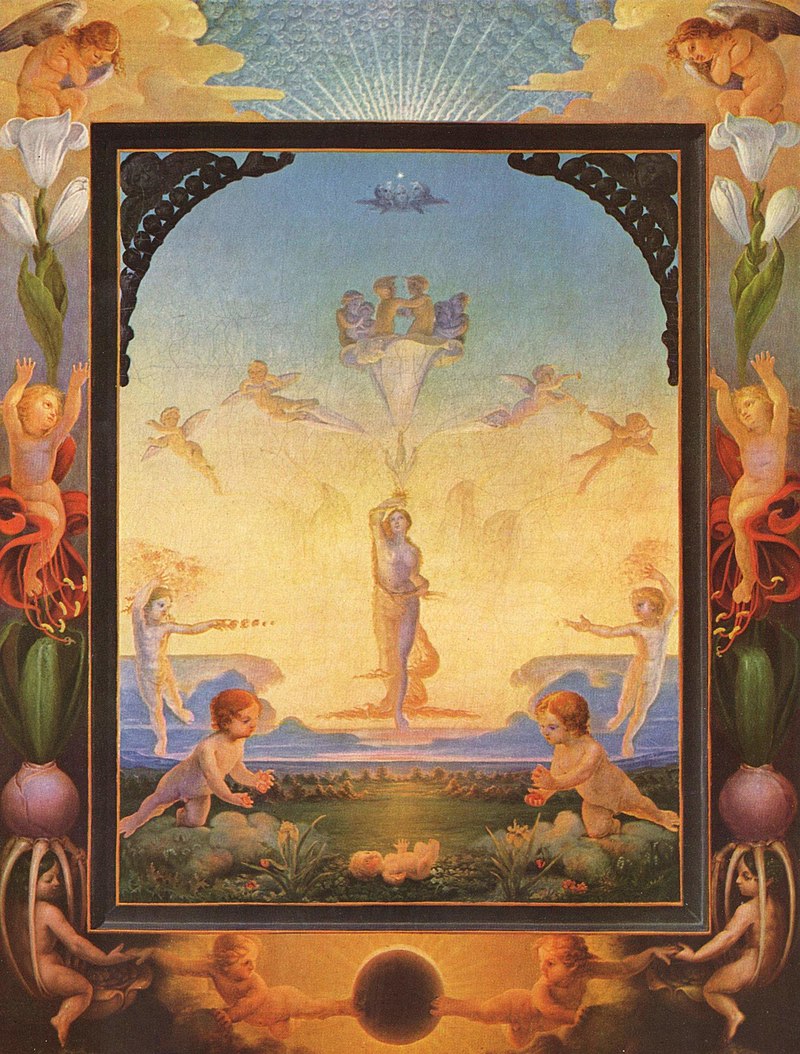

As with some other romantic artists, Runge was interested in Gesamtkunstwerk, or total art work, which was an attempt to fuse all forms of art. He planned such a work surrounding a series of four paintings called The Times of the Day, designed to be seen in a special building, and viewed to the accompaniment of music and his own poetry. The four paintings were to be installed in a Gothic chapel accompanied by music and poetry, which Runge hoped would be a nucleus for a new religion.[7]

In 1803 Runge had large-format engravings made of the drawings of the Times of the Day series that became commercially successful and a set of which he presented to his friend, the writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. He painted two versions of Morning but the others did not advance beyond drawings, due to Runge’s death. Morning was the start of a new type of landscape, one of religion and emotion. It is also considered to be his greatest work.

Runge’s interest in color was the natural result of his work as a painter and of having an enquiring mind. Among his accepted tenets was that “as is known, there are only three colors, yellow, red, and blue” (said in a letter to Goethe in 1806). His goal was to establish the complete world of colors resulting from mixture of the three, among themselves and together with white and black. In the same lengthy letter, Runge discussed in some detail his views on color order and included a sketch of a mixture circle, with the three primary colors forming an equilateral triangle and, together with their pair-wise mixtures, a hexagon.

He arrived at the concept of the color sphere sometime in 1807, as indicated in his letter to Goethe in November of that year, by expanding the hue circle into a sphere, with white and black forming the two opposing poles. A color mixture solid of a double-triangular pyramid had been proposed by Tobias Mayer in 1758, a fact known to Runge. His expansion of that solid into a sphere appears to have had an idealistic basis rather than one of logical necessity. With his disk color mixture experiments of 1807, he hoped to provide scientific support for the sphere form. Encouraged by Goethe and other friends, he wrote in 1808 a manuscript describing the color sphere, published in Hamburg early in 1810. In addition to a description of the color sphere, it contains an illustrated essay on rules of color harmony and one on color in nature written by Runge’s friend Henrik Steffens. An included hand-colored plate shows two different views of the surface of the sphere as well as horizontal and vertical slices showing the organization of its interior.

Runge’s premature death limited the impact of this work. Goethe, who had read the manuscript before publication, mentioned it in his Farbenlehre of 1810 as “successfully concluding this kind of effort.” It was soon overshadowed by Michel Eugène Chevreul’s hemispherical system of 1839. A spherical color order system was patented in 1900 by Albert Henry Munsell, soon replaced with an irregular form of the solid.

Excerpted and adapted from: Wikipedia.com, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philipp_Otto_Runge

Audio Recording of The Nazarene Movement segment:

The Nazarene Movement

The epithet Nazarene was adopted by a group of early 19th-century German Romantic painters who aimed to revive spirituality in art. The name Nazarene came from a term of derision used against them for their affectation of a biblical manner of clothing and hair style, but those in the group didn’t really mind.

In 1809, six students at the Vienna Academy formed an artistic cooperative in Vienna called the Brotherhood of St. Luke or Lukasbund, following a common name for medieval guilds of painters. In 1810 four of them, Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Franz Pforr, Ludwig Vogel and Johann Konrad Hottinger moved to Rome, where they occupied the abandoned monastery of San Isidoro. The were later joined by other German-speaking artists with the same interests.

The principal motivation of the Nazarenes was a reaction against Neoclassicism and the routine art education of the academy system. They hoped to return to art which embodied spiritual values, and sought inspiration in artists of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, rejecting what they saw as the superficial virtuosity of later art.

In Rome the group lived a semi-monastic existence, as a way of re-creating the nature of the medieval artist’s workshop. Religious subjects dominated their output, and two major commissions allowed them to attempt a revival of the medieval art of fresco painting. Two fresco series were completed in Rome for the Casa Bartholdy and the Casino Massimo, and gained international attention for the work of the “Nazarenes”. However, by 1830 all except Overbeck had returned to Germany and the group had disbanded. Many Nazarenes became influential teachers in German art academies.

Excerpted and adapted from: Wikipedia.com, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazarene_movement

Johann Friedrich Overbeck

While as a young artist Johan Friedrich Overbeck clearly accrued some of the polished technical aspects of the neoclassic painters he trained under at the Academy in Vienna, he was alienated by lack of religious spirituality in the themes chosen by his masters. Overbeck wrote to a friend that he had fallen among a vulgar set, that every noble thought was suppressed within the academy and that losing all faith in humanity, he had turned inward to his faith for inspiration.

In Overbeck’s view, the nature of earlier European art had been corrupted throughout contemporary Europe, starting centuries before the French Revolution, and the process of discarding its Christian orientation was proceeding further now. He sought to express Christian art before the corrupting influence of the late Renaissance, casting aside his contemporary influences, and taking as a guide early Italian Renaissance painters, up to and including Raphael. Together with other disaffected young artists at the academy he started a group named the Guild of St Luke, dedicated to exploring his alternative vision for art. After four years, the differences between his group and others in the academy had grown so irreconcilable, that Overbeck (and his followers) were expelled from his own guild.

He then left Germany for Rome, where he arrived in 1810, carrying his half-finished canvas of Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem (which was destroyed much later during Allied bombing during World War II). Rome became, for fifty-nine years, the centre of his labor. He was joined by a company of like-minded artists who jointly housed in the old Franciscan convent of San Isidoro, and became known among friends and enemies by the descriptive epithet of Nazarenes. Their precept was hard and honest work and holy living; they eschewed the antique as pagan, the Renaissance as false, and built up a severe revival on simple nature and on the serious art of artist who came just before the Renaissance. The characteristics of the style thus educed were nobility of idea, precision and even hardness of outline, scholastic composition, with the addition of light, shade and colour, not for allurement, but chiefly for perspicuity and completion of motive. Overbeck in 1813 joined the Roman Catholic Church, and thereby he believed that his art received Christian baptism.

Excerpted and adapted from: Wikipedia.com, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Friedrich_Overbeck

Overbeck painted his idealized portrait of Franz Pforr in Rome in 1810. It is one of the most important Nazarene works and was intended to show his friend in a state of complete happiness. Overbeck created this work in response to a dream of Pforr’s, in which the latter saw him self as a history painter in a room lined with old masters, entranced by the presence of a beautiful woman. In Overbeck’s painting Pforr, finely dressed in old German costume, sits in the arch of a Gothic window. Like a Madonna, his “wife” is reading in the Bible as she kneels, holding her handwork. The back ground of an old German town and an Italian coast line evokes the Nazarene ideal of the inseparable bond uniting German and Italian art.[8]

Audio recording of Caspar David Friedrich segment:

Caspar David Friedrich

It seems strange now but for a while the art world turned its back on the German painter Caspar David Friedrich. His art didn’t look like that of the famous artists from France who were being heralded as the Fathers of Modern Art – the Impressionists. Their work was brushy, captured the impression of a moment, and ran riot with colour. Friedrich’s work in comparison was considered too meticulous, too precise, too finely detailed to warrant serious critical attention in the decades that followed. But in reality, while the Impressionist’s fame had an impact on the popularity of Friedrich’s work in the mid-twentieth century it is most likely that being labelled the ideological harbinger of Nazi philosophy is the thing that created a dramatic de-popularization of his work.[9] He had the misfortune, in the 1930s and 1940s, to have his art appropriated by the Third Reich and Hitler’s regime and to be declared as one of Hitler’s favorite artists. What this does to the popularity of an artist’s work, even after the death of the artist, is something akin to taking a rock and dropping it off a cliff.

Over the last few decades though the tide of opinion has turned, after Friedrich was thrust back into the art historical lime light by a fanciful book, published in the 1970s, that traced the lineage of art influence from the Romantics to the New York Abstract Expressionists.[10] Now it is generally accepted that both in his technical brilliance and theoretically in his views of what the purpose of art should be, Friedrich was as radical as they come. But if proof were ever needed again of his credentials as one of the great forerunners of modern art, then The Monk by the Sea would have to be it.

Exhibited in the Academy in Berlin in 1810 along with its companion piece Abbey in the Oak Forest, it depicts a monk standing on the shore looking out to sea. The location has been identified as Rügen, an island off the north-east coast of Germany, a site he frequently painted.

The monk is positioned a little over a third of the way into the painting from the left, to a ratio of around 1:1.6. The same ratio can be found frequently in Western art and is known variously as the golden ratio, rule or section. Aside from this nod to tradition however there is little else about this painting that can be described as conventional.

The horizon line is unusually low and stretches uninterrupted from one end of the canvas to the other. The dark blue sea is flecked with white suggesting the threat of a storm. Above it in that turbulent middle section blue-grey clouds gather giving way in the highest part to a clearer, calmer blue. The transition from one to the other is achieved subtly through a technique called scumbling in which one colour is applied in thin layers on top of another to create an ill-defined, hazy effect.

The composition could not be further from typical German landscape paintings of the time. These generally followed the principles of a style imported from England known as the picturesque which tended to employ well-established perspectival techniques designed to draw the viewer into the picture; devices such as trees situated in the foreground or rivers winding their course, snake- like, into the distance. Friedrich however deliberately shunned such tricks. Such willfully unconventional decisions in a painting of this size provoked consternation among contemporary viewers, as his friend Heinrich von Kleist famously wrote: “Since it has, in its uniformity and boundlessness, no foreground but the frame, it is as if one’s eyelids had been cut off.”

There is some debate as to who that strange figure, curved like a question mark, actually is. Some think it Friedrich himself, others the poet and theologian Gotthard Ludwig Kosegarten who served as a pastor on Rügen and was known to give sermons on the shore. Kosegarten’s writings certainly influenced the painting. Von Kleist, for example, refers to its “Kosegarten effect”. According to this pastor-poet nature, like the Bible, is a book through which God reveals Himself.

Similarly, stripping it of any literal Christian symbolism, Friedrich instead concentrates on the power of the natural climate and so charges the landscape with a divine authority, one which seems to all but subsume the figure of the monk. With nothing but land, sea and sky to measure him by, his physical presence is rendered fragile and hauntingly ambiguous.

Originally the figure was looking to the right. His feet still point in that direction. Friedrich altered this at some point, having him look out to sea. The technique of positioning a figure with their back towards the viewer is often found in Friedrich’s art; the German word for it is the rückenfigur.

Monk by the Sea, the first instance of it in his work, is somewhat atypical in that the monk being so small and situated so low on the horizon does not ‘oversee’ the landscape the way Friedrich’s ruckënfiguren generally do, like in his Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog.

The rückenfigur technique is much more complex and intellectually challenging than those found in the picturesque. Acting as a visual cue, the figure draws us into the painting, prompting us, challenging us even, to follow its example and simply look. And so we do. Yet its presence also obscures our line of vision and rather than enhancing the view in the end disrupts it. In this sense, the ruckënfigur while reminding us of the infinite beauty of the world also points to our inability to experience it fully, a contradiction that we often find expressed in German Romantic art and literature.

Napoleon’s army was occupying Prussia when the painting was completed and art historians have naturally looked to read the painting and its companion, which depicts of a funeral procession in a ruined abbey, as a comment on the French occupation. It would have been dangerous to be openly critical of Napoleon’s forces so the paintings’ political messages are subtly coded.

Both paintings – Monk by the Sea and Abbey in the Oakwood – were purchased by the young Crown Prince, Frederick William, whose mother, Queen Louise, had died a few months earlier at the age of 34. An extremely popular figure, she had pleaded with Napoleon after his victory to treat the Prussian people fairly. Her death surely would have been fresh in people’s minds when they saw the paintings, a tragic loss which was very much associated with the country’s own defeat to the French.

The presence of death is certainly felt in The Monk by the Sea, though in the monk’s resolute figure we also find a source of spiritual strength, defiance even, standing, like that gothic abbey and those German oaks in its partner piece, as much perhaps a symbol of the resolve of the nation against the foreign military rule, as of the individual faced with his mortality.

Like the British painter John Constable, Friedrich drew on the natural world around him, often returning to the same area again and again. Unlike the English painter’s more scientific or naturalist approach, though, Friedrich condensed the image so as to communicate an exact emotion. As he put it, “a painter should paint not only what he sees before him, but also what he sees within himself.” It is this inward reaching project, using color and form to reveal emotional truths, that singles him out as one of the greatest and most innovative painters of his age: a true Romantic.

Adapted and excerpted from: Ben Pollitt, “Caspar David Friedrich, Monk by the Sea,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/friedrich-monk-by-the-sea/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

Self-Reflection Question 5.2

- Ruckënfigur is a landscape compositional device and the text explains how it obscures while simultaneously enhancing the scene. Looking at Friedrich’s use of ruckënfigur as well as other image you find that have this device, how does it make you feel? Do you feel invited into the piece? Why do you appreciate it (if you appreciate it) in some images, but don’t appreciate (if you don’t appreciate it) in others?

- Robert Maclean, GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DEPARTMENT Book of the Month August 2006 Los Caprichos, https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/month/aug2006.html ↵

- Arthur Lubow, "The Secret of the Black Paintings," The New York Times Magazine, July 27, 2003, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/27/magazine/the-secret-of-the-black-paintings.html ↵

- Lubow, "The Secret," https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/27/magazine/the-secret-of-the-black-paintings.html ↵

- Lubow, "The Secret," https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/27/magazine/the-secret-of-the-black-paintings.html ↵

- Lubow, "The Secret," https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/27/magazine/the-secret-of-the-black-paintings.html ↵

- Lubow, "The Secret," https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/27/magazine/the-secret-of-the-black-paintings.html ↵

- Robert Hughes,. Nothing if Not Critical : Selected Essays on Art and Artists, (New York: A.A. Knopf) 114.; German Masters of the Nineteenth Century: Paintings and Drawings from the Federal Republic of Germany, (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1981) 190. ↵

- Google Arts & Culture, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/portrait-of-the-painter-franz-pforr-friedrich-overbeck/PwHOJJbUWjvFVw?hl=en, accessed October 3, 2020 ↵

- Alina Cohen, "Unraveling the Mysteries behind Caspar David Friedrich’s “Wanderer”," Artsy.net, August 6, 2018, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-unraveling-mysteries-caspar-david-friedrichs-wanderer ↵

- Cohen, "Unraveling," https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-unraveling-mysteries-caspar-david-friedrichs-wanderer ↵