Copyright and Open Licensing

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define the concepts of copyright, fair dealing, open licensing, and public domain.

- Explain the purpose of copyright law in Canada.

An open licence is a vital component of an open educational resource. Because of this, it is important that you understand how open licences work within copyright law. This chapter will explain the relationship between Canadian copyright law, fair dealing, and the Creative Commons open licensing system.

Attribution: “What is a copyright? [Youtube]” by Innovaction, Science, and Economic Development Canada is used here for educational purposes as outlined in the terms and conditions. The original version is accessible at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljNS5p3cqls.

Copyright Law

Canadian copyright law protects an author’s rights over their original creative works (e.g., literary, artistic, dramatic or musical works (including computer programs) and other subject-matter known as performer’s performances, sound recordings and communication signals)[1]. As soon as something is in a “fixed form” (e.g., on paper, in a saved digital file, in a musical notation)[2] it is automatically protected by copyright. In other words, an idea for a book you want to write is not protected by copyright, but the first draft of your manuscript is. Copyright protection ensures that the creator of a work has complete control over how their work is reproduced, distributed, performed, displayed, and adapted. You do not need to register your resource with the Canadian Copyright Office for this to come into effect; it is automatic. At SAIT, faculty and staff are supported in their use of copyrighted materials by the Copyright Officer at the Reg Erhardt Library.

Licensing

The copyright status of a work determines what you can and cannot do with it.[3] As you begin to explore OER for use in your classroom, it is important that you understand both who holds the rights over the works you wish to use and the works you wish to create.

Most copyrighted works are under full, “all rights reserved” copyright. This means that they cannot be reused in any way without permission from the work’s rights-holder. One way you can get permission to use someone else’s work is through a licence, a statement or contract that allows you to perform, display, reproduce, or adapt a copyrighted work in the circumstances specified within the licence. For example, the copyright holder for an article might sign a licence to provide an institution the one-time rights to reproduce their article for classroom use.

You will also need to consider copyright and licensing if you wish to create OER. If work is created within the course of employment, the organization who employed the author may be the owner of the copyright and therefore specify the licensing requirements. Additional information about assigning an open licence to a work produced at SAIT will be discussed in the Creating OER chapter.

Accessible Content

In the Introduction to OER Chapter, we reviewed the difference between OER and accessible resources. When working in a digital platform, don’t forget that linking to an online resource, whether from a general internet site or from a library database, will meet the copyright and licensing requirements. While you will not be able to retain, revise, or redistribute copies of the work, students will be able to access the content in the original location.

Fair Dealing

If an “all rights reserved” copyright resource is available, you can make a fair dealing assessment for reproducing or adapting that work. However, having explicit permission is preferable. The SAIT Copyright Officer and Librarians do not recommend using fully copyrighted works in OER projects without written permission from the work’s rights-holder. Review SAIT’s Fair Dealing Policy (AC.2.12.1, Schedule A) or contact the SAIT Copyright Officer to learn more about how to apply fair dealing.

Public Domain

Works that are no longer protected by copyright are considered part of the public domain. Items in the public domain can be reused and freely modified for any purpose by anyone, without giving attribution to the author or creator.[4]

Works in Canada typically enter the public domain 50 years after the death of the creator at the end of that calendar year, or when dedicated to the public domain by their rights-holder. The Creative Commons organization created a legal tool called CC 0 to help creators dedicate their work to the public domain by releasing all rights to it.

Review the Copyright – Learn the Basics online module from the Canadian Intellectual Property Office

Open Licences

All OER are made available under some type of open licence, a set of authorized permissions from the rights-holder of a work for any and all users. The most popular of these licences are Creative Commons (CC) licences, customizable copyright licences that allow others to reuse, adapt, and re-publish content with few or no restrictions. CC licences allow creators to explain in plain language how their works can be used by others. If you locate a work with a CC licence, you can easily determine how you can incorporate the work into your course. If you assign an open licence to your work, you allow any user to exercise the rights allowed under the licence, and cannot restrict reuse by certain individuals or parties without changing the licence itself.

Creative Commons licences will be explored in more detail in the next chapter. However, there are other open licences that can be applied to educational materials. A few of these licences are described below:

- GNU Free Documentation Licence: a copyleft licence that grants the right to copy, redistribute, and modify a resource. It requires all copies and derivatives to be available under the same licence. Copies may be sold commercially, but the original document or source code must be made available to the user as well.[5]

- Free Art Licence: The FAL “grants the right to freely copy, distribute, and transform creative works without infringing the author’s rights.” It is meant to be applied to artistic works, not documents.[6]

If you’re interested in learning more about open licences, feel free to explore the Free Software Foundation’s information on copyleft licences, some of the first licences used for open content.[7]

Why Open Licences?

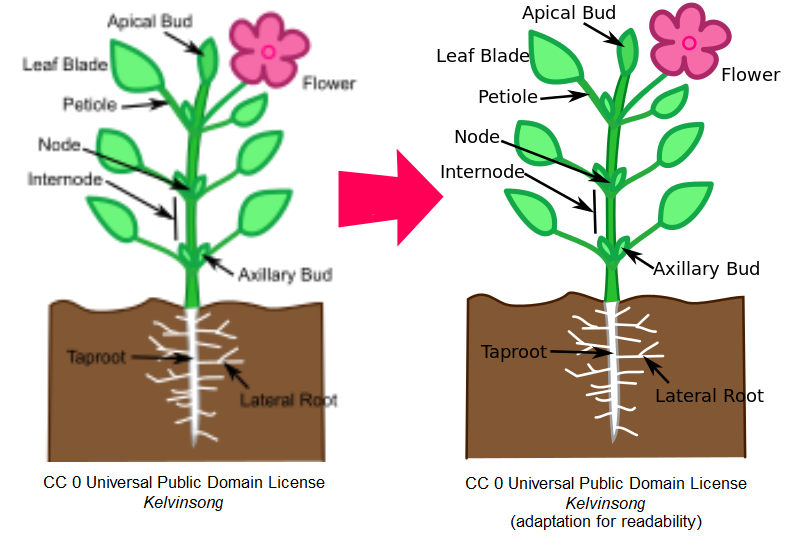

Open licences are an integral part of what makes an educational resource an OER. The adaptability and reusability of OER make it so that they are not just free to access, but also free for instructors who want to alter the materials for use in their course. For example, in the figure below an openly licensed image has been traced to make it more readable for users.

“Adaptation in action” by Abbey Elder, licensed CC 0 1.0, was adapted from “Copyrighted source to tracing” by Kelvinsong, also licensed CC 0 1.0. This image was originally used to represent an improper recreation of a copyrighted work via tracing. In this example, it shows how an already open work can be legally recreated via tracing for readability.

Early in the open education movement, David Wiley introduced what became one of the foundational tenets of the field: the 5Rs[8]. These five attributes lay out what it means for something to be truly “open”.

The 5 Rs include:

- Retain = the right to make, own, and control copies of the content.

- Reuse = the right to use the content in a wide range of ways

- Revise = the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself

- Remix = the right to combine the original or revised content with other open content to create something new

- Redistribute = the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others

While the “redistribute” and “revise” rights are the most commonly exercised rights in open education, each of the five plays an important role in the utility of an open educational resource. For example, without the right to “remix” materials, an instructor who teaches an interdisciplinary course would not be able to combine two disparate OER into a new resource that more closely fits their needs.

In the next chapter, we’ll look at Creative Commons licences and how they facilitate the expression of the 5 Rs in unique ways.

Footnotes

- https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cipointernet-internetopic.nsf/eng/h_wr02281.html#copyrightDefined ↵

- https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cipointernet-internetopic.nsf/eng/wr04784.html ↵

- Attribution: "Licensing" and "Public Domain" were adapted in part from UH OER Training by Billy Meinke, licensed CC BY 4.0. ↵

- Of course, standard citation procedures still apply for creative works in the public domain. You cannot claim another's work as your own. ↵

- Free Sotware Foundation. "GNU Free Documentation License." 2008. https://www.gnu.org/licenses/fdl.html ↵

- Copyleft Attitude. "Free Art License 1.3." 2007. http://artlibre.org/licence/lal/en/ ↵

- Free Software Foundation. "What is Copyleft?." Accessed June 29, 2019. https://www.gnu.org/copyleft/copyleft.html ↵

- Wiley, David. "Defining the 'Open' in Open Content and Open Educational Resources." Open Content blog, 2014. http://opencontent.org/definition/ ↵

A copyright license which grants permission for all users to access, reuse, and redistribute a work with few or no restrictions.

A licence permits users to certain rights over a copyrighted work. These can be exclusive (allowed for individual groups) or nonexclusive (allowed for all users). Licences can be restricted by certain factors such as purpose, territory, duration, and media (Source: Findlaw.com).

Learning materials that can be accessed freely via the general internet or library subscription but cannot be altered or shared under an all rights reserved copyright

the user's right, within copyright law, to use material from a copyright protected work (literature, musical scores, audiovisual works, etc.) without permission when certain conditions are met. People can use fair dealing for research, private study, education, parody, satire, criticism, review, and news reporting. In order to ensure your copying is fair, you need to consider several factors such as the amount you are copying, whether you are distributing the copy to others, and whether your copying might have a detrimental effect on potential sales of the original work

A set of open licenses that allow creators to clearly mark how others can reuse their work through a set of four badge-like components: Attribution, Share-Alike, Non-Commercial, and No Derivatives.

A method in which a software or artistic work may be used, modified, and distributed freely on condition that anything derived from it is bound by the same condition.