The Role of Conservation Practitioners

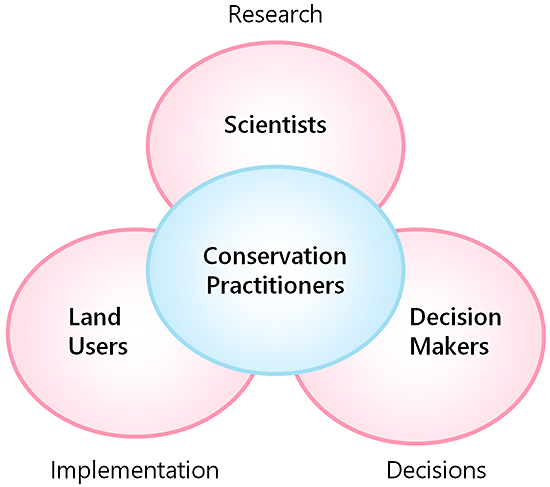

We will now shift our focus to the role of conservation practitioners, loosely defined as individuals with some form of conservation expertise working on applied conservation issues. This is a diverse group that operates at the interface between science and policy. Some conduct applied research, some engage in policy development and planning, and some oversee the implementation of conservation measures. Many serve in more than one capacity. Notably, none of the three modes of activity are exclusive to conservation practitioners (Fig. 4.6). What differentiates this group is their primary orientation toward achieving conservation outcomes.

|

Fig. 4.6. Conservation practitioners have three main roles: research, decision making, and the implementation of conservation measures. What differentiates conservation practitioners from others working in similar capacities is their primary orientation towards achieving conservation outcomes. |

As researchers, conservation practitioners are distinguished from other scientists by their focus on applied questions related to the implementation of conservation in specific settings. Thus, not all biologists consider themselves conservation practitioners, even though basic science does support conservation indirectly. In practice, the line between basic and applied research is blurred, and it is best to think of these terms as the poles of a spectrum. Furthermore, many scientists conduct both basic and applied research.

In terms of policy and planning, conservation practitioners play a critical role in synthesizing scientific knowledge about conservation and bringing it to bear in decision-making processes. Research findings locked within the pages of a journal are of no practical value until they are mobilized. How this is done depends on the type of decision being made.

At the base of the decision hierarchy are operational decisions related to the implementation of higher-level plans. For example, once a decision has been made to install a wildlife road crossing, operational decisions are required to determine the optimal location and size. These sorts of decisions are mainly technical, requiring the direct application of scientific expertise. Conservation practitioners typically have primary responsibility for decisions at this level.

Moving up the decision hierarchy, the social aspects of conservation decisions begin to predominate. This is because, as the scope of a decision broadens, more stakeholders are affected and trade-offs with competing values require greater consideration. In such cases, conservation practitioners are more likely to serve as scientific advisors than decision makers. At the highest levels, decisions are made by elected officials, even if the focus is on conservation. For example, while conservation practitioners informed the development of Canada’s Species at Risk Act, the core decisions were made by the federal cabinet.

As for implementing conservation measures, this mostly entails managing the activities of land users (both resource companies and individuals) through regulations, guidelines, and incentives. Here, conservation practitioners typically serve in an oversight role, advancing conservation through education, outreach, and the enforcement of regulations. Some conservation initiatives also feature a “hands-on” component that requires the direct involvement of conservation practitioners. Examples include habitat restoration initiatives, species reintroduction projects, and habitat management programs.

We will examine these roles in a variety of applied contexts in subsequent chapters. In Chapter 12 we will discuss skills training and the determinants of success.

Institutional Connections

Within governments, conservation practitioners are typically employed in biologist and resource management positions. Many work in fish and wildlife departments, where their focus is on species at risk and game species. Others work in forestry departments and parks departments, where they engage in conservation at both the species and ecosystem level. The range of activities of government-based practitioners is broad and includes policy development, planning, implementation, and sometimes research. These practitioners may serve either as technical advisors or decision makers, depending on the application.

As would be expected, conservation practitioners within the academic community focus mainly on research and teaching. Research programs are often structured around questions that arise out of policy and planning processes. Governments and industry, for their part, may provide funding, and over time, mutually beneficial relationships sometimes develop. Some scientists also engage in policy and planning more directly, by giving presentations and media interviews about conservation issues, providing expert advice to policymakers, and serving on planning bodies.

ENGOs are another common home for conservation practitioners. Again, the range of activities they engage in is broad. In some organizations, such as Ducks Unlimited and the land trusts, the emphasis is on directly implementing conservation measures. Other groups engage mainly in conservation planning and policy through outreach, advocacy, and participation in planning initiatives. Internally, conservation practitioners direct their group’s conservation programs and provide the scientific foundation for position statements and policy recommendations. Some groups, such as the Wildlife Conservation Society and Bird Studies Canada, emphasize applied research and publish studies in peer-reviewed journals.

Within industry, conservation practitioners are mostly employed by forestry companies as biologists and foresters. These individuals have lead responsibility for achieving the ecological objectives that forestry companies have committed to under sustainable forest management (both at the species level and ecosystem level). Their responsibilities and ability to influence harvest practices vary considerably from company to company. In some cases, funding for collaborative research is available and there is high-level support for trying new approaches. Other companies prefer to maintain the status quo.

Other industrial sectors, particularly oil and gas and mining, tend to obtain the conservation expertise they need by hiring ecological consultants on an ad hoc basis. Governments also frequently use ecological consultants, particularly now that progressive downsizing has reduced internal capacity. These ecological consultants form another pool of conservation practitioners. Much of the work these consultants do revolves around environmental assessments of large industrial projects and the associated regulatory filings, mitigation plans, and reclamation plans. Consultants with expertise and interest in the broader application of conservation science also exist, and projects and planning initiatives that require their services arise on occasion.

The Controversy over Advocacy

Advocacy is the act of publicly supporting or arguing in favour of a cause, an idea, or a policy. This may seem to have little to do with science, which is concerned with the objective study of the natural world. But in the application of science to policy problems, the line between providing scientific advice and recommending a particular course of action may be difficult to discern (Horton et al. 2016). Whether or not this is a problem has been the subject of a long-standing debate in the conservation literature (Mills 2000; Lackey 2007; Noss 2007; Nelson and Vucetich 2009). The particulars of this debate provide additional insight into the role of science in conservation.

Opponents of advocacy argue that it threatens effective decision making (Lackey 2007). Technical experts command a privileged position because decision makers look to them for reliable advice about the nature of policy issues and what to do about them (Meyer et al. 2010). The danger of advocacy is that it threatens this relationship (Lackey 2007). If experts are perceived to be advocating for a particular outcome, decision makers may question whether the advice they are receiving is truly objective and reliable. Experts may then find their advice lumped in with the value-laden views of stakeholders, to the detriment of the entire process.

Objectivity is also needed to resist the politicization of science by stakeholders who often use science-based arguments to bolster their position in public debates. Stakeholders may even seek to fund research designed to support their specific views (Jacques et al. 2008). This can tarnish the reputation of science and reduce its credibility if it leads to selective reporting of findings and other forms of distortion.

Given these concerns, the opponents of advocacy suggest that technical experts have an obligation to remain objective, neutral conveyors of scientific information (Lackey 2007). Experts should “describe empirically the way things are, not the way we think they ought to be” (Barbour et al. 2008, p. 564). Lackey (2007) provides this advice:

Be clear, be candid, be brutally frank, but be policy neutral when providing science to the public, policymakers, and others. … Often I hear or read in scientific discourse words such as degradation, improvement, good, and poor. Such value-laden words should not be used to convey scientific information because they imply a preferred ecological state, a desired condition, a benchmark, or a preferred class of policy options. Doing so is not science, it is policy advocacy. Subtle, perhaps unintentional, but it is still policy advocacy. … Why use them unless you are conveying the impression that one particular condition is preferred policy wise? A forest that has been clearcut is degraded habitat from the perspective of spotted owls and red tree voles, but it is improved habitat from the perspective of other species such as white-crowned sparrows and black-tailed deer. The science is exactly the same, only the policy context differs. The appropriate science words are, for example, change, increase, or decrease. (p. 14)

The proponents of advocacy assert that Lackey’s perspective on the role of science is fundamentally at odds with the tenets of conservation biology and applied science in general (Noss 2007; Horton et al. 2016). There is more to science than the description of natural processes; it is also a tool for achieving specific goals. Indeed, a considerable proportion of all scientific inquiry is goal oriented. For example, if we conduct a study to determine the most effective method of preventing heart disease, we are conducting goal-directed research. The results will naturally be expressed in the context of that goal: less heart disease is labelled as a positive outcome, not simply a change. It is no different for research intended to support the conservation of biodiversity.

The credibility of applied research is maintained by stating the research goals upfront and by rigorous application of the scientific method, buttressed by institutional standards and oversight (Ehrlich 2000). Concerns about objectivity apply to how studies are conducted and reported, not to the purpose of the research. Sometimes, maintaining objectivity means resisting pressure from employers or funders. More generally, it means guarding against personal biases and preconceived ideas. In the words of the physicist Richard Feynman, “The first principle [of science] is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool” (Feynman 1985, p. 313). This requires a willingness to question your own assumptions, as well as those of your field of study, and to change your opinion when compelling evidence suggests you should.

Credibility also demands honesty and openness (Meyer et al. 2010; Horton et al. 2016). Rather than hiding biases, or pretending they do not exist, they should be openly stated. In addition, researchers should speak to what they know and acknowledge when they are moving beyond their area of expertise. This includes clearly distinguishing between data, inference, and informed speculation, which are usually perceived as one and the same by external audiences (Brussard and Tull 2007). There should also be an openness about uncertainties and persistence in telling policymakers what they can reasonably expect from science, and what they cannot.

In the final analysis, both the critics and proponents of advocacy present valid arguments. It is quite possible to conduct applied conservation research that is accepted as reliable scientific information by decision makers. However, overt advocacy, particularly the promotion of specific management choices, will quickly change how the information is perceived. In practice, practitioners must make a choice. They can serve as technical experts or they can serve as stakeholders promoting conservation as a value position. But they rarely can do both at once.

Conservation practitioners also need to consider the mandate and expectations of the organizations they work for. In many organizations, particularly within government, conservation practitioners are expected to adhere to their assigned roles (Steel et al. 2004). Strong advocacy efforts by conservation practitioners may be viewed by their superiors as a challenge to their authority (Lach et al. 2003). This is especially true when statements are made publicly. Conservation advocacy may also conflict with other government mandates, creating internal discord.

The final aspect of advocacy that bears mention is advocacy on behalf of science itself. As noted earlier, science is coming under assault, to the detriment of reasoned debate and good decision making. Conservation practitioners should join with others in the scientific community to help the public understand the importance of science and evidence-based decision making (Carroll et al. 2017). For example, in April 2017, more than one million science supporters in 600 cities across the world marched in the streets to raise the profile of science and champion its importance to society (Fig. 4.7). Such efforts need to be followed up with individual everyday efforts to encourage support for science and effective decision making.