The Social and Political Dimensions of Conservation

The General Public

Conservation is a broad, multilevel enterprise with both social and scientific components. In this chapter, we will focus on the social dimension, exploring the values, perspectives, and roles of the main participants. These participants include the public, environmental groups, the resource industry, Indigenous communities, and the government. In the final section, we will examine how government policies are developed and review the current conservation policy landscape. The role of conservation science and conservation practitioners will be discussed in the next chapter.

In contrast to many other countries, 90% of Canada’s lands remain under public (Crown) ownership. This means the public has ultimate control over how most lands and resources are used, at least in principle. However, determining the wishes of the public, and sorting through the diversity of viewpoints, is far from easy. Some goals, such as the maintenance of biodiversity, clash with other goals, such as obtaining needed resources. Determining the best course of action in the face of such trade-offs is a central challenge for land and resource managers (Hauer et al. 2010; McShane et al. 2011).

The public is not only a landowner, but also a consumer. The opinions and preferences of the public are therefore of interest to companies that operate on public lands or make use of natural resources (Kennedy et al. 2009). Good alignment with public opinion may provide a boost to sales, whereas public dissatisfaction with a company’s activities can result in the loss of markets or product boycotts.

Conservationists have a keen interest in public opinions and preferences as well because experience has shown that the success or failure of conservation initiatives often depends on the level of public support. Conservation groups may attempt to shape public opinion to generate support for their projects, but they also respond to public opinion by prioritizing initiatives based on the level of public interest.

Understanding Public Opinions and Values

Public opinion about conservation issues can be obtained through surveys, but interpreting the results and applying them in a decision-making context is challenging. Public opinion can be fickle, reflecting complex contingencies that are difficult to unravel (Tindall 2003). People may also hold viewpoints that are mutually inconsistent, often because the implications are not apparent or have not been thought through.

Consider the standard unprompted question that pollsters have been asking Canadians for several decades: What is the most important problem facing Canadians today? The environment is usually among the top four responses, but its salience tends to wax and wane in synchrony with the state of the economy (Environics 2012). In 2006 and 2007, with the economy doing well, Canadians identified the environment as the country’s most pressing problem. One year later, as the effects of the 2008 recession took hold, concern for the environment was eclipsed by concern about the state of the economy and unemployment.

These findings may suggest that, when trade-offs are necessary, the economy trumps the environment in the public’s mind. However, changing the context of the question yields a different result. When people are asked what the most important problem facing the country will be in the future, if nothing is done to address it, the environment is seen as significantly more important than the economy (Environics 2013). And when presented with specific conflicts between conservation and resource development, most Canadians favour conservation. For example, in a 2017 poll, only 25% of respondents agreed with the statement “Given the economic importance of the oil industry in Canada and the thousands of jobs it provides, it would make sense to continue with oil well development even if it meant that no greater sage grouse could survive in Canada” (IPSOS 2017, p. 3).

Because public opinion is so dependent on context it is difficult to obtain reliable insight from broad opinion surveys (Tindall 2003). Truly understanding what the public feels about a specific issue requires a combination of focused issue-specific polling, public forums, workshops, and working groups. Such consultations can be effective but are time-consuming and expensive, so they are generally reserved for high-profile issues.

Another approach for incorporating public input into decision making is to focus on values instead of opinions. Values are deeply held beliefs about what is desirable, right, and appropriate (McFarlane and Boxall 2000a; Tindall 2003). The benefit of working with values is that they are more stable than opinions and less contingent on external conditions.

The values associated with the environment and nature fall into two distinct categories: utility values, which relate to a human benefit, and intrinsic values, which concern nature alone. Examples of the main types of values within each of these two categories are shown in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1. Values of nature held by Canadians.

| Value Type | Examples |

| Utility values | |

| Economic | Rents from the sale of resources, employment, food, tourism |

| Recreation | Bird watching, hiking, hunting, etc. |

| Ecosystem services | Nutrient cycling, water filtration; pollination, etc. |

| Aesthetic | Enjoyment and appreciation of the beauty of nature |

| Research/education | Learning about and understanding natural systems |

| Intrinsic values | |

| Moral/ethical | The right of species to exist and be valued for their own sake |

| Heritage | Passing on a healthy environment to next generation |

Nature-related values are often described in economic terms. The direct economic benefits of resource extraction are easiest to quantify and are closely tracked by Statistics Canada. Canada ranks among the top five global producers of agricultural commodities, newsprint, lumber, oil and gas, aluminum, nickel, gold, potash, and diamonds. The resource sector, including agriculture, currently accounts for 23% of Canada’s GDP and 24% of Canadian jobs (including indirect contributions; AAFC 2018; NRCAN 2018).

The economic benefits of non-industrial uses of nature, such as tourism, recreation, hunting, and fishing are also tracked. The Canadian Nature Survey, conducted periodically through a collaborative federal and provincial government effort, provides the most comprehensive data (CCRM 2014). In the most recent (2012) survey, 89% of adults said they participated in some form of nature-based activity during the year, and 57% took at least one trip of more than 20 km from their home to do so. Altogether, Canadians spend an estimated $41 billion on nature-related expenses per year, most of which is for transportation, accommodation, food, and equipment. Total expenditures are almost twice as high for non-motorized non-consumptive recreation as they are for motorized recreation and sport hunting combined, mainly because more people participate in non-motorized activities.

The ecological services that natural systems provide, such as water filtration and carbon storage, have historically received little attention, but that is now changing (Daily et al. 2009). The methodology for valuing these services generally relies on some form of replacement cost analysis. This entails estimating what it would cost society to replicate services that are provided for free by nature (but typically not appreciated). We will examine the ecosystem services concept in more detail in Chapter 4.

Attempts have also been made to place a dollar value on the intrinsic values of nature, using techniques such as “willingness-to-pay” surveys (Rudd et al. 2016). However, the results have not been compelling. Such studies have been criticized for being unrealistic and generating findings that are not repeatable (Nunes and van den Bergh 2001; Spangenberg and Settele 2010; Chan et al. 2012). This presents a problem because, when it comes to conservation, the moral, aesthetic, and heritage values of nature (Table 3.1) are often the primary drivers of public opinion and action. The thousands of people that took to the streets across Canada in the 1990s in protests over logging were not motivated by forest recreational values or ecosystem services. They valued nature for itself and wanted to see it protected.

Insights from Social Psychology

An alternative approach to understanding public values and opinions is provided by social psychology. Whereas economists seek to express public values in terms of a common unit of measure (dollars), social psychologists seek to characterize the range of viewpoints that exist and understand the causes of this diversity (McFarlane and Boxall 2000b).

Research by social psychologists suggests that most Canadians hold the nature-related values listed in Table 3.1 to some degree but differ in the relative importance ascribed to each. Value weightings tend to cluster in predictable ways, resulting in relatively stable and internally consistent conservation worldviews. These worldviews exist on a spectrum from anthropocentric (human-centred), in which utilitarian values are seen as most important, to biocentric (nature-centred), in which nature’s intrinsic values predominate (McFarlane and Boxall 2000a; Tindall 2003).

Among the general public, an intermediate conservation orientation is most common, implying a shift from earlier periods when utilitarian values dominated (Wagner et al. 1998; McFarlane and Boxall 2000b; Kennedy et al. 2009). Individuals with this perspective support resource extraction but will not tolerate permanent damage to the environment. There is a strong expectation of sound ecological management and a suspicion that it may not be happening. There is also strong support for creating additional protected areas (IPSOS 2017). When asked to choose between protecting jobs and protecting the environment, this group typically sides with the environment (McFarlane and Boxall 2000b; AFPA 2006; IPSOS 2017).

The public also includes individuals with more extreme views. Those with a strong biocentric orientation tend to find current management practices inconsistent with their values and favour a much more protectionist approach (McFarlane and Hunt 2006). Those with a strong anthropocentric orientation, which is least common, usually consider current management to be adequate for protecting the environment or may even feel that existing regulations are too onerous.

Personal value orientations shape attitudes toward specific issues. But attitudes also depend on awareness and knowledge about the issues (McFarlane and Boxall 2000a). In the case of biodiversity conservation, this knowledge is largely gained second-hand, because most Canadians live in cities and towns far removed from the natural landscapes that are being threatened. Organizations that control information, including the government, environmental groups, industry, and the media are therefore able to set agendas (i.e., focus attention on some issues over others) and influence opinions.

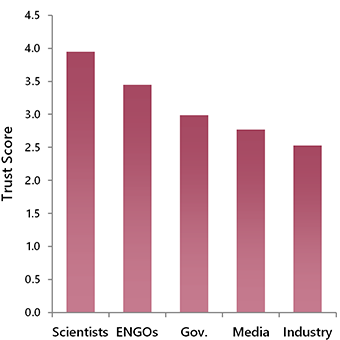

Clearcut forest harvesting provides an illustration. A person with an intermediate conservation orientation is likely to support the general idea of harvesting trees but will expect that it is done in an ecologically sustainable manner. Industry sources may inform her that clearcut harvesting is ecologically benign because it mimics natural disturbances and facilitates effective regeneration. Environmental groups may inform her that clearcutting is ecologically damaging because it simplifies forest structure and leads to the progressive loss of old-growth forest habitat. Her ultimate support or rejection of clearcutting may therefore depend, not on her conservation orientation, but on where she obtains information and the level of trust she places in different sources. Scientists and environmental groups are usually afforded a higher level of trust than government and industry (Fig. 3.1), which partially explains why public perceptions of resource development are often negative.

Attitudes toward conservation issues are also influenced by socio-economic factors (McFarlane and Boxall 2000a). The most important factor is place of residence: urban or rural. Canadian society is now highly urbanized; 69.1% of the country’s population lives in just 33 metropolitan areas, most of which are located within 100 km of the US border (SC 2015). For most urbanites, the value of resource development is as abstract as the intrinsic value of nature. For these individuals, a decision to favour protection over development is easy to make because there is little direct impact on their lives (at least nothing that is perceptible).

Canadians who live on the land or in small towns and villages see things differently. For many rural communities, resource extraction is the foundation of the local economy. So the economic benefits of natural resources are understandably more important for them than for most urbanites. Rural individuals are also more knowledgeable about land-use issues than urbanites, more engaged, and expect a greater role in management decision making (Parkins et al. 2001; McFarlane et al. 2007). They also tend to draw on industry for information about land-use issues, whereas urbanites rarely do (Parkins et al. 2001). Frustration with decisions made by far-off city dwellers can run high because rural people are usually the ones that end up bearing the burden of environmental protection measures.

Despite their dependence on resource development, it would be a mistake to assume that rural residents have a disregard for the broader values of nature. Concern with maintaining environmental health is quite high among many rural dwellers, though they are likely to prefer approaches that involve careful management over strict protection (McFarlane and Boxall 2000b; Huddart-Kennedy et al. 2009; McFarlane et al. 2011). It is also worth noting that rural residents are not all of one mind. Individuals with a strong biocentric orientation may not be as common as in urban areas, but they do exist. And many rural communities are experiencing a “greening” effect as a result of an influx of city dwellers seeking a rural lifestyle (Huddart-Kennedy et al. 2009).

To summarize, the public is not a monolithic entity. Most Canadians have a moderate to strong biocentric orientation, but a sizeable minority place greater emphasis on utility values. In either case, the public expects, and wants to believe, that the government will manage natural resources on their behalf in a way that reflects and respects their values. The implication is that resource managers must acknowledge and address the full range of values outlined in Table 3.1, not just the ones that are easily quantified. Because some values conflict with each other, compromise will usually be necessary. The public can accept that but expects the decisions to be fair and balanced.