The Historical Foundations of Conservation in Canada

A New World

The contemporary practice of conservation is rooted in the events, decisions, and learning that have occurred in the past. This applies not only to the landscape changes that now threaten many species, but also to our collective way of thinking about biodiversity and what it means to maintain it. To understand current conservation practice we need to understand its historical foundations. The aim of this chapter is to provide that foundation by tracing the evolution of conservation in Canada from the initial influx of Europeans through to the start of the new millennium. More recent developments will be discussed in subsequent chapters.

When the Europeans packed their bags for the New World, they brought with them a worldview that emphasized human dominion over the earth. European conservation practices were based on the control of land and resource use by nobility, and they were not part of a culturally shared worldview (Donihee 2000). Furthermore, in the battle for survival that characterized the lives of early settlers, wilderness was something hostile that needed to be subdued and tamed, not preserved. In any case, few could perceive the need for conservation in a land so bountiful and limitless.

The effects these early Canadians had on the environment grew with their numbers and with the expansion of the fur trade. Canada’s population increased slowly at first, remaining under 50,000 until the mid-1700s. It reached 3.5 million by the time of Confederation in 1867 (SC 2014a). Three categories of activity accounted for most environmental impacts during this early period: hunting and trapping, agriculture, and tree harvesting.

The activity with the most widespread ecological impact was trapping associated with the fur trade. Beavers were the primary species of interest, and by the late 1800s, they had been extirpated from many parts of Canada. Given the beaver’s role as an ecosystem engineer and keystone species, its removal had widespread ecological repercussions (Hood and Larson 2015). The Hudson’s Bay Company eventually instituted trapping limits as a conservation measure; however, the directives were never effectively implemented (Sandlos 2013). What ultimately saved the beaver was not conservation but changing fashion. By the mid-1800s, beaver hats were out, and silk hats were in.

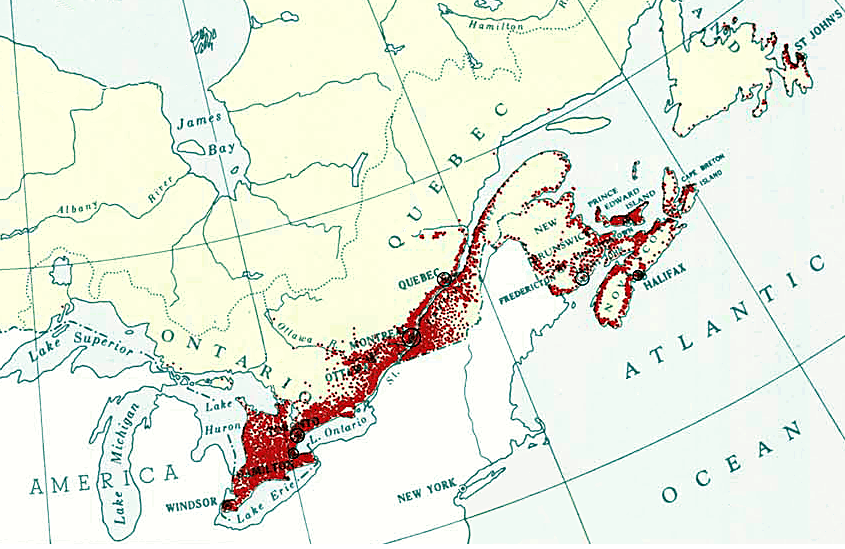

In contrast to the fur trade, which affected species and ecosystems across Canada, hunting, agriculture, and tree harvesting were concentrated near the early settlement areas. Before Confederation, almost all of these settlements were located along the St. Lawrence River, the Great Lakes Lowlands, and around the coasts of the Maritime provinces (Fig. 2.1). Agriculture had the greatest impact because it involved the clearing and transformation of land and because it supported an ever-increasing human population with an ever-growing environmental footprint.

Even though most settlers were not dependent on hunting for survival, supplemental hunting was common and resulted in substantial pressure on local wildlife. Hunted populations went into regional decline, and some species, like elk, were extirpated from some eastern areas (Rosatte 2014). Forests were also pushed back, as the need for agricultural land, lumber, and fuel for heating steadily increased. The eventual loss of 90% of southern Ontario’s Carolinian forest, Canada’s most diverse ecosystem, can be traced back to this period (Suffling et al. 2003).