10.2 Folding

When a body of rock, especially sedimentary rock, is squeezed from the sides by tectonic forces, it is likely to fracture and/or become faulted if it is cold and brittle, or become folded if it is warm enough to behave in a ductile manner.

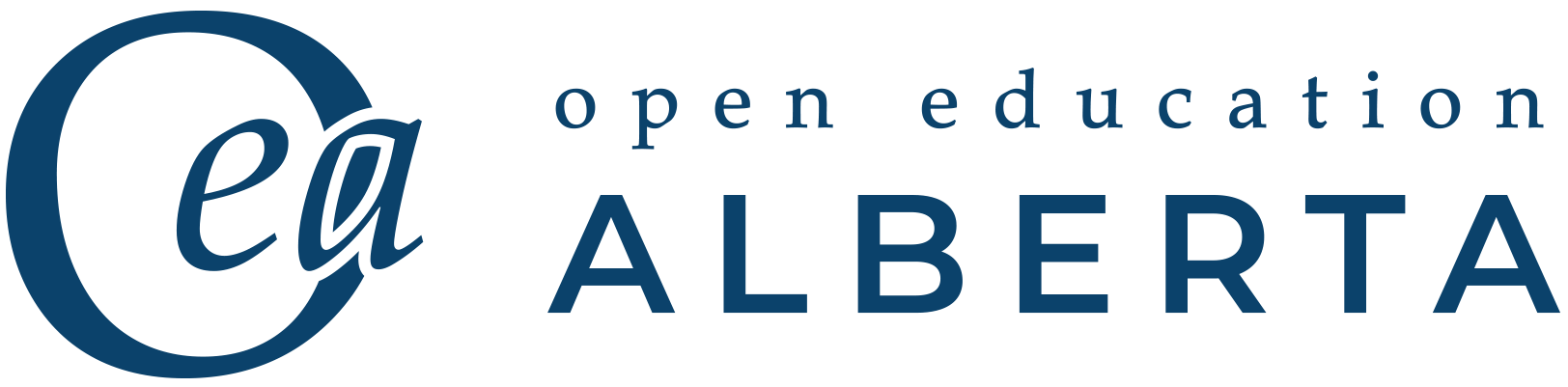

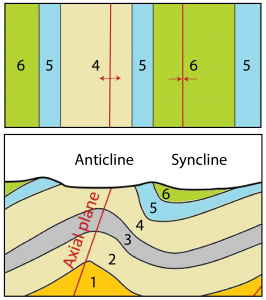

The nomenclature and geometry of folds are summarized in Figure 10.2.1. An upward fold is called an anticline (or, more accurately, an antiform if we don’t know if the beds have been overturned or not), while a downward fold is called a syncline, (or a synform if we don’t if the beds have been overturned). In many areas it’s common to find a series of antiforms and synforms (as in Figure 10.2.1), although some sequences of rocks are folded into a single antiform or synform. A plane drawn through the crest of a fold in a series of beds is called the axial plane of the fold. The sloping beds on either side of an axial plane are called the limbs of the fold. An antiform or synform is described as symmetrical if the angles between each of limb and the axial plane are generally similar, and asymmetrical if they are not. If the axial plane is sufficiently tilted that the beds on one side have been tilted past vertical, the fold is known as an overturned antiform or synform.

If the limbs dip away from one another, they form an antiform. If the limbs dip toward one another, they form a synform.

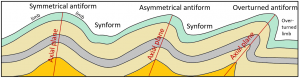

A very tight fold, in which the limbs are parallel or nearly parallel to one another is called an isoclinal fold (Figure 10.2.2). Isoclinal folds that have been overturned to the extent that their limbs are nearly horizontal are called recumbent folds.

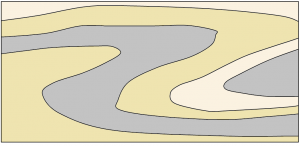

Folds can be of any size, and it’s very common to have smaller folds within larger folds (Figure 10.2.3). Large folds can have wavelengths of tens of kilometres, and very small ones might be visible only under a microscope.

Antiforms are not necessarily, or even typically, expressed as ridges in the terrain, nor synforms as valleys. Folded rocks get eroded just like all other rocks and the topography that results is typically controlled mostly by the resistance of different layers to erosion (Figure 10.2.4).

As folded rocks are eroded away, anticlines and synclines can be recognized not only by the dip directions of their limbs, but also by examining their map patterns in plan view (Figure 10.2.5). Eroded anticlines expose older rocks near the surface trace of the axial plane, and the rocks get progressively younger as you move away from the axial plane in either direction. Eroded synclines have the youngest rocks exposed near the surface trace of the axial plane, and the rocks get progressively older as you move away from the axial plane in either direction. Examine Figure 10.2.5 to confirm this: the youngest rock in the diagram (labeled ‘6’) is exposed in the centre of the syncline, whereas the oldest rock visible in plan view is exposed in the centre of the anticline (labeled as ‘4’).

Practice Exercise 10.1 Folding style

Figure 10.2.6 shows folding near near Golden, B.C. in the Rocky Mountains. Describe the types of folds using the appropriate terms from above (symmetrical, asymmetrical, isoclinal, overturned, recumbent etc.). You might find it useful to first sketch the outcrop by tracing one or two beds to get a better idea of the shapes of the folds, then sketch in the axial planes.

See Appendix 2 for Practice Exercise 10.1 answers.

Media Attributions

- Figures 10.2.1, 10.2.2, 10.2.3, 10.2.4, 10.2.6: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 10.2.5: © Siobhan McGoldrick. Derivative of Figure 10.2.4 by Steven Earle. CC BY.

an upward fold where the beds are known not to be overturned

a downward fold where the beds are known not to be overturned

a plane that can be traced through all of the hinge lines of a fold

the layers of rock on either side of a fold

a fold in which the limbs are at the same angle to the hinge

in the context of folds, where the two sides of the fold make significantly different angles with respect to the axial plane

a geological feature that has been tilted to the point where it is upside down

a tight fold in which the limbs are parallel to each other

a fold that is overturned such that its limbs are close to horizontal